![]()

1 Becoming a leader of mathematical learning

Key questions to consider

- What does mathematics leadership encompass within and beyond the classroom?

- Does leadership really matter?

- Should mathematics in school be led by one person or many?

- What is the link between formal qualifications, training, confidence and competence to lead mathematics? (Do I have what it takes?)

- What else do I need to know about in order to lead mathematics well?

- How do I know where to start?

Mathematics is well established as a core element of the primary curriculum. Often a subject that generates strong feelings amongst children and adults alike, impressions of themselves as someone who either can or cannot ‘do’ mathematics can become embedded in children’s minds before they leave primary school, and become increasingly difficult to shift. Leaders of mathematical learning, both within and beyond their own classroom, therefore need to be able to take account of a wide range of individual, school, local, national and international influences on the mathematical development, competence and confidence not only of the children in their care but also the adults working with them.

This chapter explores the importance and nature of mathematics leadership, including the types of subject, curricular and pedagogic knowledge necessary to lead mathematics learning as a teacher. It looks at different models of subject leadership and considers how the subject leader can identify priorities for leadership and sources of support. Implications for mathematics leadership are explored through the vehicle of case studies.

Overview – setting the context

In establishing what we mean by leading mathematical learning, let’s think about the experience of just one child, in one class, in one school, on any particular day. We will call her Sahdia, and place her in Year 3, the middle of her primary-aged schooling in England, in a mathematics lesson. Is she learning from a textbook or exploring practical apparatus, or both? Is she discussing with a talk partner, working in a mixed attainment group, or being taught in a top-ability mathematics set? Does she have choice of the methods she uses, or is she rehearsing a learnt technique? Is she sat at a desk, or learning outdoors? Does she evaluate her own work, believe that she can succeed if she perseveres or despair when marking reveals a page of incorrect answers? The answers to these questions, and many more besides, will come down to the nature of leadership of mathematics in her classroom, school and local area, and how it mediates the national and contemporary context to create conditions that influence her learning.

What does mathematics leadership encompass within and beyond the classroom?

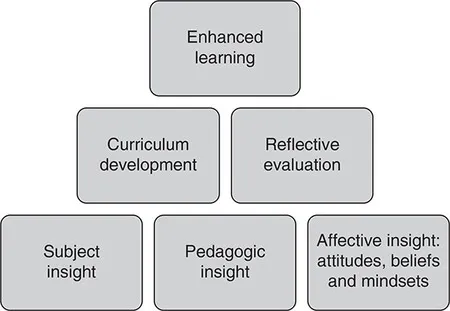

The model presented in Figure 1.1 underpins all discussion around the leadership of mathematics throughout this book. It positions the subject, pedagogic and affective insight of the leader as the starting point, with curricular and reflective evaluation building upon these and leading to enhanced learning, both of the leader and of the children in their school.

Figure 1.1 Aspects of mathematical leadership

Much has been written about the role of subject knowledge including personal mathematics qualifications, pedagogic knowledge and understanding of the detail of the curriculum, both in effective mathematics teaching itself and leadership of the subject. However, the key element of our model often missing from models of mathematics leadership is the acknowledgement of the contribution of attitudes, beliefs and mindsets in the teaching and learning of mathematics. The current or future leader has little chance of making a difference to the taught curriculum or their own reflective development, and ultimately children’s learning, if they rely purely upon subject and pedagogic insight and do not tackle attitudes, beliefs and mindsets around mathematics.

Does leadership really matter?

Whilst leadership takes many forms and is a complex and contested concept (Hammersley-Fletcher and Strain, 2010), its importance is well established: ‘School leadership is second only to classroom teaching as an influence on pupil learning’ (Leithwood et al., 2006: 4). We will take as our starting point that the approaches of leaders and what they do on a day-to-day basis have the greatest influence on outcomes, rather than the exact model adopted within a school (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2007). The impact of leadership on individual children and the adults working with them is played out through who is doing the leading, what they do and how they interact with others, and how they are empowered to carry out their role.

There have been various attempts to move forward the leadership of mathematics over recent decades in England. Perhaps the most notable of these was the Mathematics Specialist Teacher Programme (MaST) arising from the Independent Review of Mathematics Teaching led by Sir Peter Williams (Williams, 2008). Amongst other recommendations, this report proposed that each primary school should have at least one mathematics specialist teacher, drawn from the existing workforce to ‘in effect “champion” mathematics in the school and act as mentor and coach, as well as being an outstanding classroom teacher’ (Williams, 2008: 4). The role of this specialist teacher included:

- sharing responsibility for improving mathematics teaching within the school

- acting as peer coach and mentor for serving teachers, newly qualified teachers (NQTs), teaching assistants and trainee teachers

- leading collaboration within and between schools

- leading on intervention for children struggling with mathematics and provision for those identified as mathematically gifted and talented.

Although the MaST programme ended in most areas long before the number of mathematics specialists envisioned by Williams was reached, it left a considerable legacy. Its model, with its three-fold foci of subject knowledge, pedagogy and collaborative working with others, was acknowledged as a success (Walker et al., 2013) and is drawn upon to underpin the models of leadership advocated here.

More recently, there has been a two-pronged attack in increasing the proportion of teachers able to take a specialist role in leading mathematical learning in the primary school. The first of these relates to the provision of mathematics specialist routes into initial teacher training, supported by an increased training bursary. The second relates to the initiatives coordinated by the National Centre for Excellence in the Teaching of Mathematics (NCETM), for example those targeted at developing mastery and funded as part of the ‘Maths Hubs’ programme in the United Kingdom. These latter initiatives focus on those already teaching and leading mathematics. If the new leader of mathematics is feeling daunted, remember that these large-scale models are just one aspect of leadership; actions taken on a day-to-day basis within your own classroom or influencing peers are just as important if not more so.

Should mathematics in school be led by one person or many?

With a growing awareness of the limitations of individual leadership (Harris, 2010), much of the focus of leading mathematics follows a distributed model, in which many people play a part. To a certain extent all teachers are leaders, sometimes purely of learning in their classroom but often more widely as they seek to support and influence the practice of others. In this way leadership of mathematics in the primary school comes in various guises, many of which will be explored in greater detail within the remainder of this book. Leadership may entail, for example:

- leading children through learning a new topic or approach

- developing a new calculation policy to be implemented throughout the school

- working with a cluster group of schools to develop a new assessment approach

- monitoring and evaluating standards and progress for different identified groups of children

- purchasing and developing the use of new resources to support a practical approach to developing number sense

- leading parental workshops targeted at helping parents to play mathematical games with their children

- trying out a new approach to marking before sharing it with colleagues

- identifying, researching and disseminating local best practice in integrating ICT or outdoor learning into teaching.

In other words, mathematical leadership should be embedded throughout every level of interaction in the primary school, from the trainee or NQT leading learning in their own class for the first time, to the head teacher and governing body with ultimate responsibility for standards and progress across their school. These aspects of leadership are influenced in turn by what might be seen as the ‘macrosystem’ (Bronfenbrenner, 2009): the social and cultural influence of national policy making, changing curricular models and assessment systems. As can be seen in our first set of case studies, leaders operate in a wide range of contexts with varying levels of sole or collective responsibilit...