Introduction

Imagine a school in which mathematics lessons were taught in the swimming pool or where children had voice-activated pencils. Or at a more mundane level, classrooms in which children did not scrape their knees on tables, had blinds to keep out the sun and enough space to move around, free from clutter. Imagine schools run on flexible timetables where children could spend more time studying their interests, or ‘schools without walls’ where children could learn outside with immediate access to animals and wild gardens. These were the responses of primary and secondary pupils to a competition in 1997 run by The Guardian called ‘The School I’d Like’. It was re-run of a similar competition held thirty years earlier (Blishen, 1973). Both generations wanted more time to be creative, a theme that has continued in follow-up competitions and surveys. As one 6-year-old put it: ‘Children sometimes have better ideas than adults. That is because the children’s brains are new and not old’ (Birkett, 2011).

There are schools around the UK that have taken up some of these ideas. For instance, quiet or sensory rooms are increasingly popular although they tend to be used for children with behavioural or learning difficulties. Even the more fanciful ideas have been supported by teachers and backed by academic research. Take the child who wanted to walk around the school on pink fluffy carpets in her socks. One study spanning twenty-five countries over ten years reports that children who learn in a ‘shoeless’ environment are more likely to behave better and obtain good grades than peers with footwear (Pells, 2016). The deputy head at one East Midlands primary school reports a calmer and more relaxed atmosphere after it was decided that children could wear slippers in class. The researchers claim that cleaning costs are lower, furniture lasts longer and children’s reading improves – as they can read in more comfortable positions (Khomami, 2017). It is important then not to underestimate children’s thinking capabilities.

Studies reveal that before children enter the world they are learning. Remarkably, their senses are so well developed that they can recognise sounds and face-like shapes before they are born (Knapton, 2017). The question of when babies first develop powers of conscious thinking is more debatable (Koch, 2009). We simply do not know whether this is in the womb, at birth or during early childhood. The field of baby research is a contentious one, but there are claims that six-month-old babies can reason and display far greater intelligence than was once thought (Saini, 2013). Scans suggest that their brains work incredibly hard just to look at a stranger’s face and it takes about a thousand hours to commit this to memory (Livingstone, 2005). Around the age of one, children begin to point at things and effectively ask the question with their finger: ‘What is this?’ As young children explore their surroundings, they ask questions and make connections between new experiences and what they already know. By eighteen months, toddlers can make connections – if provided with a toy rake and an out-of-reach toy, they will realise that the rake can be used to retrieve the toy. Young children are keen to find things out. By the time they are four, one study suggests children ask their caregivers, on average, more than 100 questions every hour. Two-thirds of these questions are designed to elicit information such as the names and purpose of objects (Chouinard, 2007). By the age of seven, and with the right support, children can use ‘thinking’ language such as ‘guess’, ‘know’ and ‘remember’, reason logically, hypothesise, suggest alternative actions that could have been taken in the past and understand that the beliefs of others may be different from their own (Taggart et al., 2005).

In short, young children are natural thinkers – curious, imaginative and eager to learn. In this book, we explore how teachers can build on these traits and inclinations. We begin by considering the meaning, nature and scope of thinking.

What is thinking?

Thinking can be defined in many ways. Edward de Bono (1976: 33) offered a concise definition that remains a useful starting point: ‘Thinking is the deliberate exploration of experience for a purpose’. This is helpful because it highlights the deliberate and purposeful aspect of thinking which interests educators – the purpose may vary, from seeking to judge, plan, evaluate, create and so on. Smith (1992: 9) defined thinking as ‘the business of the brain’ although increasingly cognitive psychologists are recognising the influence of the whole body and feelings on how we think (Claxton, 2015). In physical terms, thinking is a biological process whereby brain cells (neurons) connect with each other through electrical impulses. Once neurons connect, they form a network of pathways. As these pathways are used repeatedly, the connections become permanent. These connections are strengthened through interactions with the environment and through natural maturity (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Neuron pathways

However, we remain very much in the dark about how these billions of neurons achieve thinking (Ramachandran, 2011; Solomon, 2015). Ignorance has led to speculation and misinformation. Hence neuroscientists have been busy correcting the myths that have emerged from the industry, such as we only use 10 per cent of our brain or that there are left- and right-brained people. Brain-based pedagogies such as brain gym and visual, auditory and kinaesthetic (VAK) learning styles have also been widely discredited (Coffield et al., 2004; Geake, 2009). Unfortunately, we are easily seduced into thinking that there is scientific credibility behind anything that features pictures of a brain. Measuring what goes on in the mind has remained one of the greatest challenges in the history of psychology (Wooldridge, 1994). And yet, despite the reservations associated with brain-based research in the next decade or so, it is forecast that neural implants could improve our powers of memory and reasoning by 30 per cent (Dodgson, 2017). Rather than struggle to learn a language, an implant might save the effort. The lines between artificial (computer) and human intelligence are becoming increasingly blurred.

On a more philosophical level, thinking can be defined as the ability to reason that sets humans apart from other animals (if not computers). This is expressed, for instance, in the application of logic to solve complex problems and the application of literacy skills. McLeish (1993: 1) estimated that in a lifetime (presumably spanning seventy or so years), each human learns, ponders and applies fifteen billion items of information. This is the process of thinking that we know so little about. As De Bono (1976: 8) put it, ‘thinking is a most awkward subject to handle’. Even the notion of thinking as being a matter of reasoning is contentious. While we have the capacity to think rationally we often act very irrationally. Some people habitually leave things to the last minute, even though they know in plenty of time that they have a deadline to meet. From a rational perspective, many of us who are overweight know that it is in our best interests to reduce sugary foods, drink water rather than alcohol and walk several miles a day. The writer Dan Ariely (2010) points out that occasionally there are unexpected benefits from defying logical thinking. Trusting instinct can sometimes triumph over logic and considering every detail. Instinct draws upon in-built mental shortcuts (heuristics), which saves overly complicated analysis. Hence, we tune into our names if mentioned in a crowd and can filter out everything else we hear.

Historically speaking, the word ‘think’ has carried several meanings. It developed from Old English, first appearing in the supernatural poem Beowulf composed around 1,300 years ago (Barnhart, 1988: 1134). It originally meant to imagine something so strongly that it appeared real to oneself. It is now the seventy-ninth most widely used word in the English language, based on an analysis of more than two billion words by the Oxford English Corpus. Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of 1755 illustrated how, over the centuries, the word had evolved to have several meanings:

- To have ideas; to compare terms or things; to reason; to cogitate; to perform any mental operation;

- To judge; to conclude; to determine;

- To intend;

- To imagine; to fancy. (Lynch, 2004: 498–499).

These definitions demonstrate the critical, purposeful and creative aspects of thinking, although the imaginative element in the fourth definition has been relatively neglected.

Most modern dictionaries follow Johnson’s first definition of thinking as the mental process of reasoning about something, usually an issue or problem. Adey (2002: 2) defines thinking simply as ‘something we do when we try to solve problems’. But problem-solving is only one thinking skill. ‘Thinking skills’ is used as an umbrella term to cover a range of mental processes which require learners to ‘plan, describe and evaluate their thinking and learning’ (Higgins et al., 2005: 1). When they were first included in England’s National Curriculum in 1999, five sets of skills were identified:

- Information-processing skills – to locate, collect and analyse information

- Reasoning skills – to give reasons, draw inferences and make deductions

- Enquiry skills – to ask relevant questions, pose and define problems, plan research, test conclusions and improve ideas

- Creative thinking skills – to generate and extend ideas, suggest hypotheses, apply imagination, and to look for alternative innovative outcomes

- Evaluation skills – to evaluate information, judge value and to have confidence in judgements (DfEE/QCA, 1999).

Since then, as we will discuss in Chapter 2, there have been significant revisions to the curriculum in England, which have seen thinking skills lose their explicit status although the phrase remains alive in other parts of the UK and further afield (e.g. Donaldson, 2015; OECD, 2016).

Winch (2010) offers a balanced and insightful discussion about the controversies associated with ‘thinking skills’ such as whether they can be genuinely regarded as skills, applied in a range of different contexts and taught independent of subject disciplines. He concludes that despite philosophical differences there is a consensus that no thinking skills intervention should be introduced without carefully weighing up its scope, limits and evidence of impact.

One of the limitations in using the term ‘thinking skills’ is the implication that teachers need only to focus on skills to develop thoughtful learners. Hence some writers prefer the broader term ‘capacities’ (Lucas and Spencer, 2017) or ‘competences’, which is a combination of knowledge, skills and attitudes. The importance of cultivating the right attitudes and dispositions towards learning and thinking is now widely recognised. A child may acquire higher-order thinking skills, such as the ability to read between the lines, but not be disposed to read regularly. Katz (1993: 16) describes dispositions as:

‘A pattern of behavior exhibited frequently and in the absence of coercion and constituting a habit of mind under some conscious and voluntary control, and that is intentional and oriented to broad goals.’

As discussed further in Chapter 10, by developing dispositions such as open-mindedness, curiosity and flexible thinking, children are more likely to become lifelong learners, effective problem-solvers and decision-makers.

In summary, several writers have confirmed that thinking and thinking skills may well be fluid concepts but argue that this should not put teachers off from promoting thinking in the classroom. For instance, Resnick (1987), suggests that thinking skills are hard to define, but possible to recognise, while McGuinness (1999) suggests that there are common processes and attributes that constitute thinking – these include collecting, sorting, analysing and reflecting. What is important to realise is that thinking can develop, change and improve with support, experience and direct teaching. Therefore, while defining and classifying thinking may be difficult, this should not put teachers off from pursuing thinking in the classroom.

Types and quality of thinking

In everyday life, we think in different ways. At times, this can be sequential as we process information in an orderly, linear manner. We make lists, follow directions, predict outcomes and recount events. On other occasions, we may think holistically to gain the bigger picture and see how different parts fit together. A good garage mechanic, doctor or computer technician will try to understand the whole ‘system’ and work through various scenarios before deciding upon the correct diagnosis and action. In academic disciplines, there is a need for both sequential and holistic thinking. For example, historians need to think about the chronology of events in determining when things happened in the past but they also need to study society as a whole: the relationships, values and beliefs, as they try to explain motives.

Designers use creative processes such as experimenting, creating prototype models and redesigning. ‘Design thinking’ places learners in the context of how designers operate. They need to solve technical problems but they also need to understand the product or service from the viewpoint of user and producer. Sharples et al. (2016) identify the teaching of design thinking as one of the innovative pedagogies that might transform education. Challenges can be set for pupils so that they begin to understand the design process. These challenges should include a setting (e.g. a local park), characters (e.g. parents, animals, children) and a potential problem (e.g. litter, vandalism, possible closure). The design process involves posing questions and considering alternatives (e.g. How might we keep the park clean? What if we redesign the pathways? Can we raise income by hosting an event?)

Much of our thinking can be very random and unplanned, such as when ideas come into our heads while out walking the dog or during a shower. We often carry out tasks such as driving and housekeeping without much conscious thought. However, we can easily slip into autopilot with potentially lethal consequences. Drivers who lose concentration, for example, cause nearly half of all car accidents; a poll of 27,000 drivers by the Automobile Association found that a quarter of 25–34-year-olds struggled to recall parts of their journey. In the classroom, we are more interested in the kind of conscious thinking, which we can influence. This thinking is deliberate and purposeful, whether helping children to recall historical facts, solve numerical problems or plan an outing. As De Bono (1991: 9) points out, we need to separate ‘what goes on in our heads all the time from the more focused thinking that has a purpose’ (our italics).

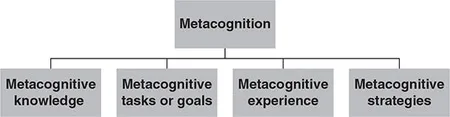

One particularly relevant concept here is ‘metacognition’ (Flavell, 1976), often simplistically described as ‘thinking about thinking’ (McGuinness, 1999; Hattie, 2009). It more accurately refers to the beliefs and knowledge individuals hold about their cognitive processes and their ability to manage these processes. As Figure 1.2 shows, metacognition involves processes beyond simply knowing (cognition). Metacognitive knowledge involves how we see ourselves as learners and thinkers. Metacognitive experience refers to how well we feel we are doing a task, i.e. the degree of confidence, satisfaction or puzzlement, while metacognitive tasks or goals describe what we intend to gain from a cognitive activity. Metacognitive strategies or skills refer to knowing which methods to use and when to use them, as well as monitoring and evaluating learning from the success (or failure) of the strategy used.

Figure 1.2 Overview of metacognition

Higgins et al. (2014) suggest that supporting metacognitive approaches to learning offers a high impact, low cost way...