eBook - ePub

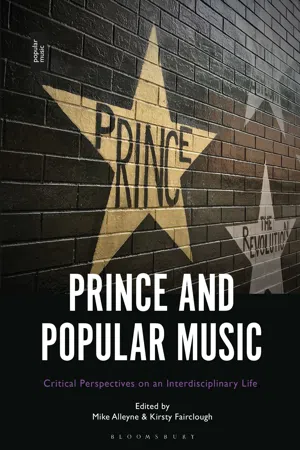

Prince and Popular Music

Critical Perspectives on an Interdisciplinary Life

This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prince and Popular Music

Critical Perspectives on an Interdisciplinary Life

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Prince's position in popular culture has undergone only limited academic scrutiny. This book provides an academic examination of Prince, encompassing the many layers of his cultural and creative impact. It assesses Prince's life and legacy holistically, exploring his multiple identities and the ways in which they were manifested through his recorded catalogue and audiovisual personae. In 17 essays organized thematically, the anthology includes a diverse range of contributions - taking ethnographic, musicological, sociological, gender studies and cultural studies approaches to analysing Prince's career.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Prince and Popular Music by Mike Alleyne, Kirsty Fairclough in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Sound and vision

1

Baby, I’m a star

Prince’s Purple Rain

Jason Wood

From the relatively early days of cinema, figures from the world of popular music have been cast in acting roles. The reasons are legion and run from a desire to maximize branding to a drive to capitalize on a specific audience, with teenagers being a recurring target demographic, and, on relatively few occasions, to an actual ability to act. Both Harry Belafonte and Frank Sinatra certainly had something of the actor about them.

In the 1950s and 1960s it became relatively commonplace for figures such as Elvis Presley, Cliff Richard, The Dave Clark Five and The Beatles to feature in movies specifically crafted to trade on their tidal waves of popularity. Head (Bob Rafelson, 19681 ) and Slade in Flame (Richard Loncraine, 19752 ) seemed to kill off the pop band star vehicle for good. But then the phoenix rose from the ashes when The Spice Girls were given their own movie.3 If only, as Cher sang, ‘I could turn back time.’4

What is relatively clear is that most music performers don’t have to struggle to make it as actors, treading the boards and appearing in B-movie-type fare (or worse still, on television – that is, before it became the new cinema); by the time they are in the main cast in motion pictures, they are already famous. The opportunity to appear on screen also usually corresponds with that moment when they are about to transcend stardom. To quote Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965), they ‘suffer a fate worse than death’, they ‘become a legend’. This legendary status turns them into living brands, which presents to music and film executives the potential to make an awful lot of money.

Though he was already a star by the time of Purple Rain (1984), his first and, in fact only, critically and commercially most successful big screen endeavour, the film helped to cement the legend of Prince Rogers Nelson. Emerging as Prince’s record sales finally began to match his prodigious output and with him behaving as if he were already a star (certainly in his reserving the right to dress without regard for convention, and this in the face of a relative lack of airplay for extremely personal LPs such as Dirty Mind, 1980, and Controversy, 1981), the film was lightning in a bottle. Capitalizing on the huge sales of the pre-release album of the same name, which appeared in stores some months prior to the film’s release, shifting 1.5 million copies in America in its first week alone, Purple Rain was a perfect synthesis of rock ’n’ roll fable and autobiography.

But before returning to Purple Rain in more specific detail we need to lay a little more pop star on film groundwork, as a number of more general observations that follow are pertinent in regard to Prince. They also perhaps help to provide some context as to why his parallel big screen stardom burned both brightly and briefly.

As the counterculture began to take hold in the 1960s the casting of pop stars became less about brand and profit, and more about a desire to capture a spirit of rebellion or mystique. Directors sought a certain ‘otherness’ – that elusive quality that separates stars from mere mortals. One immediately thinks of Marianne Faithful in Jack Cardiff’s The Girl on a Motorcycle (1968), Mick Jagger in Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970), Dennis Wilson and James Taylor in Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) and Bob Dylan in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973, also featuring Kris Kristofferson). David Essex impressed in Claude Whatham’s That’ll Be the Day (1973, also featuring Ringo Starr), a role he reprised in Michael Apted’s Stardust (1974, also featuring Adam Faith). Roeg proved himself perhaps the master of casting alchemy, persuading David Bowie to play an emaciated alien in The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and then drawing a good performance from Art Garfunkel in Bad Timing (1980).5 John Lydon also got in on the act, proving rather credible as a sneering psychopath who makes crooked New York cop Harvey Keitel his quarry in Roberto Faenza’s Order of Death (A.K.A Cop Killer, 1983). With his refusal to conform and the fusion of black R&B, white guitar rock and overtly sexual lyrics and persona, Prince certainly had one foot in the counterculture camp.

Throughout the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s a relatively select number of pop stars and high-profile musicians went on to achieve successful parallel careers: Tom Waits, Cher, Deborah Harry, Yasmin Bey (aka Mos Def), Will Oldham (who began as an actor, appearing in Matewan, 1987, for John Sayles), Iggy Pop and Justin Timberlake. But not Sting, never Sting, though he does appear in Radio On (1979), Chris Petit’s majestic paean to the road movie genre and the new wave pop music of the early 1980s, a decade about to have Thatcher’s stilettoed heel held unceremoniously and callously to its throat.

Other pop figures of the era and the intervening years had acting careers that more or less came and went: Bjork (The Juniper Tree, Nietzchka Keene, 1990, and Dancer in the Dark, Lars von Trier, 2000, which put her off acting for good), Grace Jones (Vamp, Richard Wenk, 1986), Michael Hutchence (Dogs in Space, Richard Lowenstein, 1986) and PJ Harvey (The Book of Life, Hal Hartley, 2000) to name but four. It’s instructive to note that in each instance the aforementioned were playing variations of themselves; one of the prerequisites for casting a pop star is that the star should at least be recognizable to their fans or perform as a thinly veiled version of themselves.

Madonna tried desperately to run a parallel acting career, shining in Desperately Seeking Susan (Susan Seidelman, 1985), but then stumbled ever after in under-par fare such as Body of Evidence (Uli Edel, 1992), which traded without subtlety on the association with Madonna and sex. M adonna also offers evidence of a popular theory that many pop stars equip themselves well in their first role but then falter thereafter as they move away from roles for which they are tailor-made to those for which they are actually required to act. Five words: Mick Jagger in Ned Kelly (Tony Richardson, 1970). Standing in front of a movie camera and attempting to turn on the charisma is not always the same as taking the stage to an audience of screaming and adoring fans. Prince was unable to sustain a film career post his debut in Purple Rain, in which he appears as himself, filmed performing actual concerts around which a rather tenuous and hackneyed narrative is spun, though he did have two more stabs at it with the largely lamentable Under the Cherry Moon (1986) and the utterly regrettable Graffiti Bridge (1990).

Madonna, like Prince, with whom she battled it out for dominance in the MTV era, is a figure whose presence in a film project frequently extends to a vocal performance or theme song. This raises the awareness of the project in question while also appeasing those who follow the artist in order to buy their music. In short, it’s another marketing and money-generating opportunity. It doesn’t always work out, as was the case with Bowie’s aborted (or reportedly rejected) score to The Man Who Fell to Earth. However, images from the film did adorn two Bowie albums of the period: Station to Station (1976) and Low (1977), again maximizing marketing impact. Prince of course wrote all the music for Purple Rain, which contained the anthemic When Doves Cry and the title track, and of course for his subsequent two movies. He would continue to offer his services as a soundtrack composer for others, perhaps most significantly to Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) and Spike Lee’s Girl 6 (1996).

The casting of iconic reggae star Jimmy Cliff in The Harder They Come (Perry Henzell, 1972) certainly leant the film added authenticity in terms of the social, geographical and political Jamaican landscape it depicted. Described as ‘Jamaica’s very first feature’, the presence of Cliff, who also contributed to the score after enjoying crossover success in America, would also have attracted the reggae fans and Jamaicans to whom the film would have wished to appeal. Following the cycle of exploitation of Black American cinema, the rise of hip hop culture led to a call to depict on screen with more integrity and diversity the lives of young Black Americans experiencing everyday racism, intolerance, deprivation and inequality. Films such as Boyz n’ the Hood (John Singleton, 1991), Juice (Ernest R. Dickerson, 1992) and Set It Off (F. Gary Gray 1996) cast, respectively, Ice Cube, Tupac Shakur and Queen Latifah to great effect, utilizing their affinity with their communities, their spokesperson-like status and their rising popularity predominantly but not exclusively among Black consumers of African American film, music and culture.

Purple Rain goes to great lengths to satisfy Prince’s Black and White fan bases. He appears as the son of a Black father and a White mother, and it is interesting how the audience at the club that is so central to the drama are almost exclusively mixed couples. Cynthia Rose observed that as ‘well as depicting the perpetual conflict between men and women, with the only unity being carnal’,6 another motif of Prince’s life and work, the fact that a number of the key relationships and issues at the heart of Purple Rain are Black and White in terms of race is recurrence enough that it can but assume clear resonance.

Readers of this chapter will no doubt be more than familiar with the film but in terms of a concise synopsis, it stars Prince as ‘The Kid’, a Minneapolis musician escaping a tumultuous home life through writing and performing with his band, The Revolution. Desperate to avoid making the same mistakes as his errant, domineering father, ‘The Kid’ rises through the Minneapolis club scene and his rocky relationship with the singer, Apollonia. However, though ‘The Kid’s’ incredible writing and performing prowess seems sure to set him on the path to romance, redemption and stardom, another musician is waiting in the wings to capsize his dreams and steal his crown.

The directorial debut of film school graduate Albert Magnoli, who would go on to collaborate with Prince on a number of subsequent pop promos,7 Magnoli’s suitability for the project was displayed in his debut short, Jazz, the tale of three Los Angeles jazz musicians. The short came to the attention of Prince’s management who hired Magnoli to overhaul a script originally written and conceived by William Blinn. Softe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- Part One Sound and vision

- Part Two Purple performance and presence

- Part Three Gender

- Part Four Politics and race

- Index

- Copyright