![]()

Chapter 1

Diagnosing the Problem

The black lung movement breached the wall of silence that conceals the work-related diseases and deaths of workers in the United States. In 1968, it launched a controversy over occupational health that has persisted on and off to this day. Textile workers fashioned a brown lung movement after coal miners’ example.1 Asbestos workers pressed for a federal compensation program similar to that covering disability and death from black lung.2 With increasing frequency, trade union activists have included occupational safety and health protections among their collective bargaining demands; in the legislative arena in 1970, they secured the federal Occupational Safety and Health Act patterned in part after the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969.3 Despite the many tangible accomplishments of the black lung movement, including an unprecedented federal compensation program and strict respirable dust standard designed to prevent the disease, coal miners today experience in their bodies the injustice that they fought to eliminate more than fifty years ago (see photos 2 and 4). One-fifth of underground working miners in central Appalachia who have twenty-five or more years on the job show evidence of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP), one of the ensemble of occupational respiratory diseases that miners call “black lung.”4 Moreover, they are contracting the most advanced, breath-robbing form of CWP—pulmonary massive fibrosis, or PMF—at the highest rates ever recorded.5

Coal miners and their families possess insights about why this resurgence is occurring, but their perspectives differ in important ways from prevailing explanations.6 The latter include technical approaches that analyze factors like increased silica content in mine dust, and liberal political accounts that emphasize governmental regulatory failure.7 By contrast, many unionized miners have long focused on their power relations with the coal operators, those who own and supervise the mines, as fundamental to their health as well as safety. This is not to suggest that either the composition of dust or the content of regulation is irrelevant. Rather, such factors unfold within historically specific class dynamics that function to restrain or intensify the hazards of mining. When miners have enjoyed significant leverage in the workplace, they have been able to, for example, refuse unsafe work and insist on accurate dust sampling (photo 1). However, in the present period—indeed, for more than forty years now—miners and their trade union, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), have been under attack, and miners’ bargaining power is considerably weakened. Digging Our Own Graves traces these transformations in the balance of power between underground miners and operators within the overall political economy of the bituminous coal industry, and, drawing on the testimony of miners themselves, analyzes the social and economic production of black lung.

The Saudi Arabia of Coal

Central Appalachia, including eastern Kentucky, southern West Virginia, and southwest Virginia, is the contemporary epicenter of black lung disease.8 During the late nineteenth century, this region of thickly forested mountains and modest farms alchemized into “coalfields,” as companies bought land, built towns from the ground up, and hired men of diverse racial and national backgrounds to retrieve from the earth rich deposits of bituminous coal.9 Classic elements of the “resource curse”—thwarted economic development, anti-democratic politics, economic whipsaws of boom and bust, endemic poverty—soon became apparent in this rural region.10 But central Appalachia is also the site of extensive popular organizing and collective resistance. Long before the black lung movement began in southern West Virginia, Appalachian coal miners banded together and, during three long decades of hard-fought strikes and armed confrontations, sought to join the UMWA. In 1933, they largely succeeded.

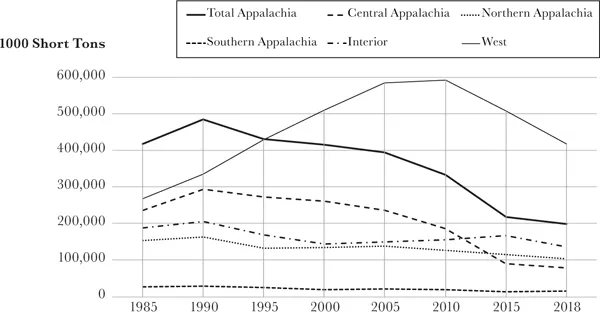

Today, some two decades into the twenty-first century, the Appalachian coal industry is in the doldrums. Since 2000, the region’s coal production (both surface and underground) has fallen by half, with central Appalachia accounting for 84 percent of that drop. By contrast, output nationwide fluctuated but, until 2012, generally rose.11 However, the geographic center of the industry shifted: in 1993, after more than two decades of exponential growth, vast surface mines in the Powder River Basin and other areas west of the Mississippi River surpassed Appalachia as the primary locus of production, most of it thermal coal destined for utilities. That market is now in a tailspin nationwide due to closures of coal-fired electric plants and competition from renewables and natural gas.12 Central Appalachia’s top-grade metallurgical (met) coal, once produced for the large domestic steel manufacturers that owned most of these mines (photo 3), has become increasingly subject to the vagaries of the export market. In southern West Virginia and southwest Virginia, where most of the coal produced is metallurgical, total underground output shrank by more than 60 percent from 1994 to 2019, and, in 2018, more than 40 percent of this area’s metallurgical production was shipped out of the US.13 Faced with long-term collapse in domestic market demand, Appalachian coal operators disingenuously but successfully positioned themselves as embattled allies of their workers against former President Obama’s presumed “war on coal.”14

Chart 1. US Bituminous Coal Production by Region and Year

For definitions of terms, geographic areas, and other details that appear in the charts, see the explanatory note in the appendix.

Sources: US Energy Information Administration, Coal Industry Annual 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000; Annual Coal Report 2005, 2010, 2015, 2018.

The changing political economy of the Appalachian coal industry helps make sense of certain technical factors that epidemiologists and other scientific researchers fault for the rise in black lung. These include positive correlations between lung disease and small mines (fewer than fifty workers), longer work hours, rank of coal, and the practice of cutting into silica-laden rock.15 One analysis of working miners’ chest X-rays taken by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Coal Workers’ Health Surveillance Program from 1970 to 2009 concluded that workers from small mines were five times as likely as workers in larger operations to contract PMF. This tendency is evident in X-rays beginning in the 1980s, then worsens considerably in subsequent decades.16 In roughly the same period of time, 1978–2008, data from the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) indicate a large jump (by almost one-third) in the number of hours that miners work each year.17 As for the composition of dust, researchers have long known that the higher the rank of coal, ranging from low-rank soft lignite (“brown coal”) to anthracite, the more damaging its respirable dust; virtually all central Appalachian coal is medium or high rank.18 Since 1980, chest X-rays of miners from West Virginia, Kentucky, and Virginia increasingly revealed a type of opacity associated with silica exposure as well; indeed, X-rays taken during 2000 to 2008 reveal a 7.6-fold increase in this opacity over those from the 1980s.19 Since black lung typically takes several years to manifest on an X-ray, these findings suggest that developments in central Appalachian coal mining, beginning in the late 1970s and intensifying thereafter, have been increasingly hazardous for miners’ health.

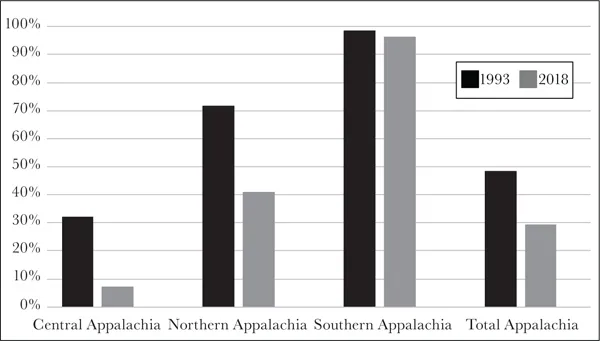

Ask UMWA miners about these trends and their explanations vary, but they often include the workplace consequences of the fierce, protracted, and ultimately successful anti-union offensive that certain operators spearheaded in the late 1970s. (See chapters 7 and 8.) Between 1973 and 1992, UMWA membership plummeted by more than 50 percent, from an estimated 213,000 to 82,000. By 1993, only 32 percent of the 32,000 underground miners in central Appalachia belonged to the UMWA; as of 2018, union density had dropped much further, to 7 percent.20 Given the region’s large pool of surplus labor, miners’ realistic fear of job loss, and the weakened position of the UMWA, union representation cannot guarantee protection against bosses’ demands for productivity, regardless of safety and health. But, without the union, there is little protection at all.

Lack of a worker organization to counter unreasonable or abusive employers is significant in any workplace, but it is especially so in an industry as inherently dangerous as underground coal mining. Longer hours, which of course increase dust exposure, are a direct result of working without a union contract that specifies the circumstances in which miners work overtime. Changes in working conditions are less easily quantified but equally important. Retired miner Terry Lilly:

I had to go to nonunion because I couldn’t find a union job … When you work nonunion, you have no voice … You didn’t hang curtain [used to control ventilation], you didn’t ask about curtain, you didn’t ask about dust pumps [devices for sampling respirable dust]. It was all pretty much, “This is what you’re going to do.” I think the coal miners lost their voice, and I think their voice is in the UMWA.21

Chart 2. Percentage of Workers in UMWA at Underground Mines in Appalachia and Subregions, 1993 and 2018

Sources: US Energy Information Administration, Coal Industry Annual 1993, Table 45, pp. 66–67; Annual Coal Report 2018, Table 20, p. 35.

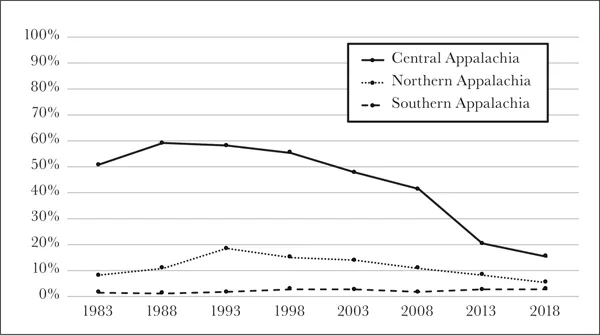

Ownership of the Appalachian coal industry also began to transform during the 1980s. Following a brief heyday in the wake of the Arab oil embargo of 1973–1974, when coal became the reliable, seemingly limitless domestic energy source and drew new investment from major oil companies, among others, the Appalachian portion of the industry began to decline. Expanded production of low-sulfur, surface-mined coal from thick seams in the West, prompted in part by the Clean Air Act of 1970, drove a long, downward slide in the price of thermal coal. Simultaneously, demand for Appalachia’s top-grade metallurgical coal tanked along with the fortunes of domestic steel producers, whose output fell by one-third from 1974 to 1984.22 Faced with shrinking profitability, some larger operators in the East began to hire small, nonunion contractors to mine their coal more cheaply. Others, including Big Oil and, eventually, domestic steel, began to divest their coal holdings; by 1990, oil company ownership of coal was back to its 1970 level.23 As get-rich-quick expectations escalated during the 1990s throughout US businesses, “vulture” capitalists began circling the eastern coal industry, stripping assets from larger coal operations, selling off mines one by one, and sometimes declaring bankruptcy, a legal maneuver that typically allowed them to shed contractual obligations to pay unionized miners’ retirement and health benefits for life.24 Underground employment in the region declined precipitously and, in central Appalachia, those who were able to find jobs increasingly worked in small mines. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, even as coal nationwide became more concentrated in ownership, the central Appalachian coal industry became increasingly fractured, unstable, and nonunion.25

Chart 3. Percentage of Underground Miners at Small Mines in Appalachian Subregions by Year

Source: MSHA Mine Data Retrieval System, available at https://www.msha.gov/mine-data-retrieval-system.

UMWA miners describe the working conditions in small, nonunion mines, so-called “dogholes,” with particular disdain. Mines with relatively few employees have long been the bane of the UMWA: they are difficult to organize and, even when miners elect to join the union, the undercapitalized coal operators who often own such mines may seek to evade their contractual obligations to pay into UMWA benefit plans. Unable to invest in expensive equipment to increase productivity and, hence, profitability, more marginal operators of small mines tend to extract as much value as possible from miners’ hard labor. Retired miner Danny Whitt, from southern West Virginia, describes working in such a mine:

I worked at one [small, nonunion] mine. They told me when they hired me, “When you come to work here, we don’t pack a lunch bucket. We don’t have time. If we break down, we want you either shoveling [coal] on the belts, or hanging curtain, or hanging cable, or something.” They really had bad equipment, old equipment, trying to get by cheap as they can, mine coal and make money. Their primar...