eBook - ePub

Developing Sustainable Planned Communities

- 221 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Developing Sustainable Planned Communities

About this book

Get practical how-to information on designing and developing attractive, profitable, and environmentally responsible planned communities. This book includes 10 case studies of successful projects in the U.S., the U.K., and Australia

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

IMAGINE ENTIRE COMMUNITIES conceived and constructed in harmony with nature. No degraded resources. No wasted energy. No toxic materials. Lots of green space. Such places would be beautiful, walkable, healthy, and designed to last.

And they are being built now. The past two decades have seen the emergence and increasing marketability of a new kind of development. Whether referred to as “green” or “environmentally sensitive,” a sustainable community can produce a triple bottom line for residents, developers, and the planet: environmentally friendly, economically profitable, and socially sustainable developments.

Few would argue with such benefits. The challenge is in realizing them. It is easy to label a community sustainable; making it so requires a commitment to thinking differently about what development means. A sustainable community is a holistic entity. Like an ecosystem, sustainable development is about interrelationships. From conception through development and maintenance, a sustainable community balances environmental, social, and economic imperatives. It is about more than energy-efficient buildings. It is about reducing the impact of development on the natural environment and creating a mix of uses and housing types. It is about regionally interconnected public transportation, green spaces and stormwater management systems that reduce runoff. A community that fosters a healthy relationship between people and nature is sustainable.

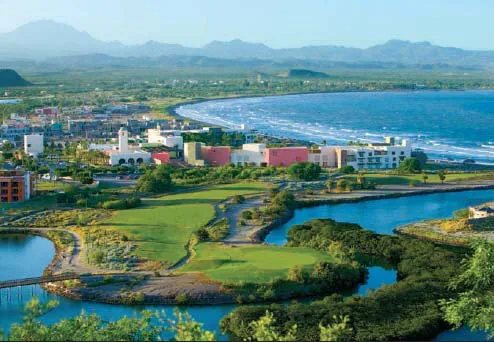

Based on the three pillars of sustainability—environment, society, and economy—the Loreto Bay community on Mexico’s Baja Peninsula has made sustainable development its primary goal.

DARREN DEWARDS PHOTOGRAPHICS

A Greener Future

An early response to the 20th-century’s spread of soulless subdivisions and their commercial-strip counterparts was the rise of large master-planned communities such as The Woodlands near Houston, Texas, and Irvine Ranch in Orange County, California. Realized in the 1970s, these projects and others like them have stood the test of time because of their focus on the physical elements of community design that enhance livability, facilitate social engagement, emphasize open space, and incorporate a mix of uses and housing types.

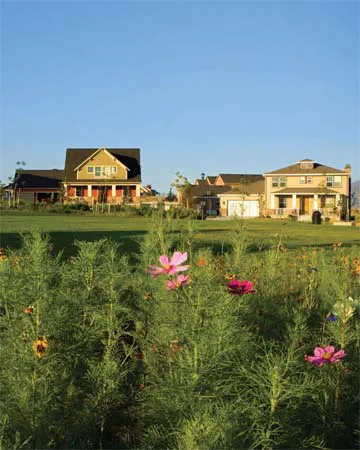

Daybreak, South Jordan, Utah. Sustainable communities foster an intimate relationship between people and nature.

ED ROSENBERGER

United Kingdom developer BioRegional Quintain Ltd. is planning to build a carbon-neutral community in Middlesbrough, where residents will live in individually designed “sugar cube” apartment blocks.

ZEDFACTORY.COM

Issaquah Highlands in Washington has banned culs-de-sac and front-loaded garages in favor of shared front yards.

FUSIONPARTNERS, LLC

Sustainable communities share many of these same characteristics, but they place greater weight on environmental sensitivity. Such communities sit lightly on the land and incorporate many environmentally friendly products and strategies. Green building practices stress energy efficiency, water conservation, and native landscaping, and improve indoor air quality with nontoxic paints, carpets, and other materials.

However, sustainable communities do more than incorporate ecologically sensitive building technologies and materials. They integrate green principles into every aspect of a community’s planning, design, construction, and maintenance. Choosing a sustainable site is also important. It is difficult to be truly green if a project is constructed on prime farmland, a historic site, or endangered-species habitat. Ideal locations for sustainable communities include brownfields, decommissioned military bases, vacant parcels, and infill sites. If a greenfield site is unavoidable, sustainable communities must minimize site infrastructure and grading, maximize sediment control, limit landscaping to new or restored native vegetation, and provide easy access to public transportation.

And the development community is taking these challenges seriously. Based on data collected in a joint 2003 survey, Residential Green Building SmartMarket Report, the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) and McGraw-Hill Construction have forecasted a surge in environmentally responsible efforts: “By 2010, the value of the residential green building marketplace is expected to boost its market share from $7.4 billion and 2 percent of housing starts last year to $19 billion to $38 billion and 5 to 10 percent of residential construction activity.”

And with good reason. Buildings consume 37 percent of the nation’s energy and 68 percent of electricity, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Buildings also produce about 30 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. With global warming and other damaging effects on the environment on the rise and an increasingly savvy home-buying public demanding healthy, energy-efficient houses, the development community’s future can only be one color: green.

Shades of Green

There are many “shades of green,” ranging from full-spectrum green to one-dimensional strategies with few ecological or social benefits. “Greenwashing,” which occurs when a conventional project is dressed up with slick, nature-oriented marketing, is among the worst offenses. These developers and builders recognize that “green” has become fashionable, so they use their marketing budgets to try to reposition their projects.

A more genuine shade of green is the “conservation development,” or what some people call a “low-impact development.” These communities conserve a substantial amount of open land by clustering houses in walkable neighborhoods. They reduce the surface area paved with impervious materials and use a variety of techniques to reduce stormwater runoff and protect wildlife and natural settings.

In his 1969 book Design with Nature, landscape architect Ian McHarg advocated a careful analysis of the site to foster a greater sense of harmony between natural systems and the built environment. His ideas, along with those of Randall Arendt, a well-known land use planner, have influenced a generation of planned communities, ranging from Prairie Crossing, a conservation community outside Chicago, to The Woodlands, one of the largest and most successful master-planned communities in the country.

The developers of these communities recognized that neighborhoods that engage the natural world were good for both people and wildlife. In fact, many conservation-minded developers take pride in helping to restore the land, removing invasive species, improving water quality, and building trails.

Unlike conventional developments, where natural features are often replaced with automobile-oriented environments, turf grass, and undifferentiated housing stock, conservation developments have grown in popularity because homebuyers value natural open spaces, native plants, wildlife, and beautiful surroundings.

Arcosanti, located in the high desert of central Arizona, was conceived in 1970 as an antidote to wasteful land use practices. The experimental town is designed according to the concept of “arcology” (architecture + ecology), developed by Italian architect Paolo Soleri.

ARCOSANTI FOUNDATION

While they demonstrate outstanding site planning and careful approaches to natural systems, some of the early manifestations of conservation development could be labeled “grass green,” because they mainly addressed horizontal land development issues, albeit in a thoughtful way. A more comprehensive approach addresses not just land development but also a wide array of issues involving the design, materials, and building methods for new homes, offices, and businesses. The home-building and real estate industries have established standards for houses and other structures based on sound environmental principles.

The nonprofit U.S. Green Building Council, founded in 1993, for example, has created the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Green Building Rating System, a nationally recognized benchmark for high-performance sustainable building practices. These standards address everything from indoor air quality to energy efficiency and construction-waste management.

The NAHB has also developed green building guidelines for residential construction, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has created the Energy Star program to help businesses and individuals protect the environment through superior energy efficiency. The EPA has certified some 300,000 homes that are at least 15 percent more energy efficient than the standards set by the 2006 International Energy Conservation Code.

Sustainability, however, is more than effective insulation, high-performance windows, or efficient heating and cooling systems. In the Ecology of Place, Timothy Beatley, one of the world’s leading experts on the subject, notes that creating sustainable communities is not simply a matter of preserving a few wetlands, saving a few acres of open space, or establishing a few best management practices. It is a matter of considering ecological limits and environmental impacts throughout the entire development process, from the energy efficiency of buildings to the proximity of a regional transportation system. It is also about people. Truly sustainable communities take a holistic approach that benefits the residents, the natural environment, and the developer. It is full-spectrum green.

Sustainable communities are not just greener. They can be healthier and safer than conventional developments. Winston Churchill once said, “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” His point, of course, was that the physical character of our communities affects who we are and how we relate to one another and to our surroundings.

Sometimes the consequences of development patterns and resource usage are obvious. When neighborhood green space is lost to development, children lose a place to play and their parents lose a place to socialize. Long commutes, one result of sprawl, contribute to air pollution but also to the loss of free time. The more electricity we use, the higher our utility bills will be and the more greenhouse gases we will emit into the atmosphere.

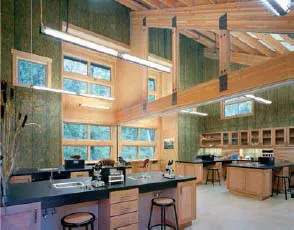

At the Island-Wood Wetland Lab on Bainbridge Island, Washington, many building materials were locally sourced, recycled, and reused to help connect the project to its site and surrounding ecosystem.

©MITHUN

All native plantings were removed during construction of the Four Seasons Resort Scottsdale at Troon North in Arizona and then transplanted back into the natural plant groupings found and documented on the site.

© 2007 EDAW/PHOTOGRAPHY BY DIXI CARRILLO

However, many consequences of development choices are less obvious, particularly in the areas of physical and mental health. A growing body of research shows that how we design our communities and buildings has a profound effect on human health. One example is the relationship between walkable communities and childhood well-being. According to federal transportation studies, approximately half of all school children walked or rode a bicycle to or from school in 1969. Today, fewer than 15 percent walk to or from school, a statistic that speaks to the health care crisis facing our youngest citizens.

Another effect of sprawling development patterns is what author Richard Louv calls “nature-deficient disorder.” In his book Last Child in the Woods, Louv argues that children need to have a stronger connection to the natural world, if they are to truly flourish as healthy citizens of the planet. He points out that our schools may teach students about threats to the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Authors and Reviewers

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword by Jonathan F. P. Rose

- Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Sustainable From the Start

- 3 Integrated Planning and Design

- 4 The Costs and Benefits of Sustainable Development

- 5 Green Building Design

- 6 Maintaining Sustainability

- 7 Case Studies

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Developing Sustainable Planned Communities by Richard Franko,Jo Allen Gause,Jim Heid,Steven Kellenberg,Jeff Kingsbury,Edward T. McMahon,Judi G. Schweitzer,Daniel K. Slone,Jonathon Rose in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.