- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Richly illustrated with color photographs, site plans, and diagrams, this book explains how to design and develop pedestrian-friendly, mixed-use developments.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

“The street is the river of life.”—William Whyte

The typical American today leads a sedentary lifestyle—sitting all day at work, taking the elevator instead of the stairs, driving instead of walking, and watching television for recreation. People spend a large part of the day in cars—isolated from others, dealing with road rage, and looking for the best possible parking space at each destination. Although the amount of time people spend exercising as a leisure-time activity has remained constant for years,1 what has dropped is the amount of exercise that people get from their daily activities—in particular, from walking or biking for transportation.

Today’s sedentary habits represent a significant lifestyle change that has occurred since the mid-20th century. The built environment that has emerged over the past half-century is now designed to support inactive lifestyles. Communities and commercial districts are vehicle oriented: they offer an abundance of parking and are accessed via wide, highspeed roadways with little accommodation for pedestrians or bikers. Workplaces are isolated in office or industrial parks, so that workers must drive to run errands or to go out to lunch. Stores are separated from neighborhoods and from each other, so that shoppers cannot complete errands on foot, but must instead drive from one store to the next. People are isolated in residential neighborhoods, in which their homes are increasingly likely to offer the amenities and entertainment options that used to be available only in public places.

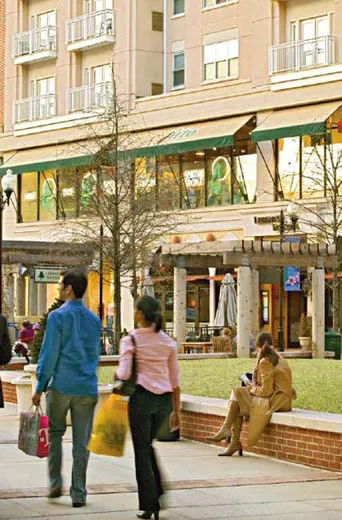

More people would get exercise as part of their daily lives if the built environment supported pedestrians, bikers, and transit. Mixed-use, transit-oriented developments, like Pentagon Row, in Arlington, Virginia, are a step in the right direction. RTKL Associates

A growing body of evidence points to connections between physical and mental health and the built environment. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), regular physical activity reduces the incidence of some of the leading causes of death and disability, including heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, colon cancer, and depression. A 2003 report, “The Relationship between Urban Sprawl and Physical Activity, Obesity, and Morbidity,” is the first national study to find a clear association between the built environment and activity levels, weight, and health.2 The report, which analyzed 448 counties across the United States, found that the residents of the most sprawling county in the country weighed an average of six pounds (2.7 kilograms) more than the residents of the most compact county. The study also cites national polls indicating that 55 percent of Americans would like to walk more and that 52 percent would like to bike more. The researchers concluded that many more people would get exercise as part of their daily activities if the environment in which they lived and worked supported a more active way of life. The study suggests a number of solutions:

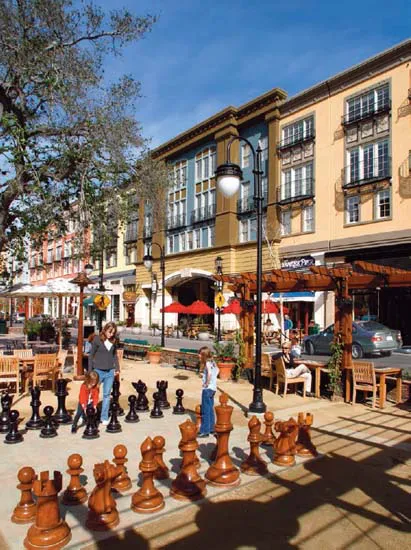

Human-scale open space is being reintroduced to shopping centers. Santana Row, in San Jose, California, includes a variety of interesting public squares and an attractive sidewalk environment. Jay Graham, SB Architects

All of these recommendations can be made part of the tool kit to create places that are more active, more pedestrianfriendly, and ultimately more profitable for developers.

The Landscape Today

America is a nation of drivers. On the surface, the nation’s reliance on automobiles seems quite fitting for a modern society. But allowing the automobile to shape the environment, and everyone’s lives, neglects the civic and social infrastructure that supports community. As architect and author Jan Gehl has said, “Life takes place on foot.”

Since the 1950s, widespread automobile ownership has opened larger, less expensive tracts of land to millions of people and made possible the sprawling land development patterns that have emerged, including the suburban model of separated land uses. Today, most residential areas are located miles from the shopping districts, workplaces, schools, and recreational and cultural facilities that support them. Widely dispersed residential developments, many of which lack sidewalks altogether, and massive stretches of retail, with their attendant moonscape of parking lots, make walking or biking more than just difficult; it can be unsafe, unpleasant, and often impossible. As Robert Dunphy, Senior Resident Fellow for Transportation at the Urban Land Institute, has noted, “Currently, conventional greenfield development patterns make transit expensive and underused, render carpooling ineffective, and discourage walking and biking.”

Although a growing number of national retail establishments are oriented toward pedestrians, the majority employ designs that favor the automobile. Standard suburban strips and big-box retail centers, in particular, give preeminence to automobile access. Retailers conduct market research by traffic counts and select locations on the basis of highway access and visibility. They require large swaths of visible, convenient parking right out in front. If a sidewalk exists at all, using it is unpleasant and often dangerous—as is traversing the football field of asphalt between the sidewalk and the store. It is equally difficult to walk from one shopping center to an adjacent one because connections are lacking. Shopping centers are often separated by grass swales, untamed wooded areas, fences, loading areas, or other obstacles.

Ground-breaking developments like Mizner Park, in Boca Raton, and Seaside, Florida, have shown the value of distinctive, pedestrian-oriented environments. Left: Cooper Carry, Inc. Right: Adrienne Schmitz

Long commutes rob working people of their free time, but the dispersal of uses hits the oldest and the youngest particularly hard. Children must rely on parents for transportation; few kids can walk down the street to the park for a game of baseball or to the corner store to buy candy. Seniors who can no longer drive are effectively trapped, unable to shop in their neighborhood or to get out and see friends and family without assistance.

Parks, squares, and other open spaces that contribute to the public realm are often either missing from today’s commercial districts and residential communities or are inappropriately located or designed. By the mid-20th century, most cities had invested in major park systems, yet their residents were moving to the suburbs, where they believed there were better opportunities for recreation. In fact, the very suburbs to which city dwellers moved had little parkland—and in many of these areas, it was already too late to create major public parks because the best sites were being transformed into residential subdivisions. Moreover, most residents were unwilling to dedicate the funds to pay for public parks. The result is that suburban residential subdivisions—unless they are very large—lack public open space. In many areas where small clusters of development dominate, there are no greenway systems or parks to speak of.

Numerous impediments remain to the development of compact, walkable, mixed-use development; architect and planner Andrés Duany summarizes them as follows:

Despite these and other obstacles, the landscape has begun to change. Had this book been written five or ten years ago, conditions would have been described in far more bleak terms. Throughout the country, communities are beginning to reflect the positive changes—in particular, the emphasis on a pedestrian presence—brought about by smart growth and the new urbanism. Downtowns are being rebuilt with a mix of commercial and residential land uses side by side, or stacked one above the other. Some cities have even torn down outmoded and unnecessary highways that ripped through their cores.

Many new towns and villages—beginning with Seaside, Florida, in 1980—are designed primarily to support pedestrians rather than vehicles. In CityPlace, in West Palm Beach, Florida, local government and private developers worked together to create a strong, pedestrian-oriented downtown where none had existed. In 1990, Reston Town Center, in Northern Virginia, was developed as the walkable downtown core for a vehicle-oriented suburban community originally developed in the 1960s.

Steiner + Associates, based in Columbus, Ohio, has built its reputation on pedestrian-oriented retail development. According to Yaromir Steiner, president of the firm, t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Form and Function: Creating the Pedestrian Experience

- Chapter 3 The Business of Pedestrian-Oriented Development

- Chapter 4 Public Sector Involvement

- Chapter 5 Healthy Trends

- Chapter 6 Case Studies

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Creating Walkable Places by Adrienne Schmitz,Jason Scully in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.