![]()

![]()

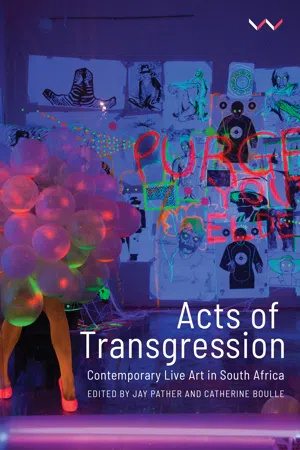

CHAPTER 1

Artistic Citizenship, Anatopism and the Elusive Public: Live Art in the City of Cape Town

NOMUSA MAKHUBU

But then because you have to do all this, when you get to the final step, something strange has happened to you and you speak the way a drunk walks. And, because you are speaking like falling, it’s as if you are an idiot, when the truth is that it’s the language and the whole process that’s messed up. And then the problem with those who speak only English is this: they don’t know how to listen; they are busy looking at your falling instead of paying attention to what you are saying.

NoViolet Bulawayo, We Need New Names1

On an early summer’s evening in 2017, passersby stop to see why a crowd has gathered in Long Street, Cape Town, and discover two black women taking off and putting on their clothes. These ‘ghels’ speak isiXhosa, teasing the audience. Using township lingo, they direct their statements to onlookers familiar with what is being said, but also to those who seem oblivious to their taunting assertions. Seeing these ghels may be titillating and amusing for some, but to others, these women are indecent, discomforting and even vulgar. Their expressions, articulations and gestures may seem to belong to black townships and therefore appear ‘out of place’ in the central business district (CBD). The transgressive linguistic strategy of this work points to the fact that most white and coloured people in Cape Town (and South Africa) do not speak isiXhosa and so cannot listen to what is being said.2 The performance points to continuing racial segregationism in South Africa and, more significantly, to a profound sense of not belonging.

This work by Buhlebezwe Siwani and Chuma Sopotela, titled Those Ghels, formed part of the 2017 Institute for Creative Arts (ICA) Live Art Festival, held in Cape Town, which also featured Khanyisile Mbongwa’s kuDanger!, Sethembile Msezane’s Excerpts from the Past and Dean Hutton’s #fuckwhitepeople. These works, as I show in this chapter, explore intertwined themes of spatial segregation, language and displacement. By so doing, they demonstrate the critical impulse in contemporary live art in South Africa to question volatile identities through spatial politics, and to locate them within the incoherence and incongruence of postcolonial urban spaces. I argue that this form of creative protest constitutes a radical intellectual creative language, which deciphers the psychological and emotional burden of historical prejudice, reinforced through racial and class division. The sense of being out of place – ‘anatopism’ – articulated in these works is not only crucial in questioning the race-gender-class matrix within conditions of postapartheid citizenship, but is also critical to uncloaking violent processes of unhoming that continue today.

My argument locates these works within a psychogeography of anatopism, pointing directly to dispossession and a deep sense of alienation. The term ‘psychogeography’ is often associated with the Situationist International, a Marxist organisation that sought radical change by constructing ‘emotionally provocative situations’ and ‘collective ambiences’ in public, and by countering the alienation caused by capitalist processes.3 Guy Debord characterises psychogeography as ‘the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, whether consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.’4 It arises in response to social relations emerging from the design of modern cities, which heightens social difference. Debord and other Situationists created various interventions and encounters precisely to probe the spatial politics of modern cities. I use the term here to draw from its radical stance towards class politics and how such politics manifests in urban planning and organisation. I apply it cautiously, however, to the intricacies of the postapartheid South African context where the sense of not belonging emerges from the longue durée of colonial settlement, land dispossession, forced removals and racialised economic segregation.

Using the lexicon of the township, Those Ghels, Excerpts from the Past and kuDanger! offer sharp criticism of persistent segregationism. Performed in the CBD, these interventions probe, implicitly and explicitly, the conditions of apartheid in postapartheid South Africa, a context in which race determines various forms of alienation. Many black, isiXhosa-speaking people are forced to learn English to access work, while most white and coloured South Africans would not recognise an insult in isiXhosa. These interventions engage not only with anatopism in post-apartheid South Africa, but also with a growing feeling of resentment in response to unchanging racial attitudes. The key themes of language and place intimate a sense of anger at the refusal of white South Africans to share living spaces (affluent suburbs remain predominantly white, while townships remain completely black), or to reciprocate by means of learning an African language. In the city of Cape Town – regarded by many as the country’s ‘hub of racism’ – live art interventions unmask raw, unreconciled sentiments about apartheid and postapartheid injustices.5

Live art encompasses a variety of interdisciplinary, open-ended interventions in which situations and encounters are created. Lois Keidan describes it as a ‘cultural strategy’; ‘art that is immediate and real, and art that wants to test the limits of the possible and permissible.’6 Live art often grapples with a combination of socio-political concerns and emerges from the ‘developing crossover of “art”, “performance art” and “theatre” practices,’ which gives ‘rise to increasingly explicit concerns for the “integration”, “intersection” or “hybridisation” of arts practices in time-based “live” work.’7 A performative practice of ‘disrupting borders, breaking rules, defying traditions, resisting definitions, asking awkward questions and activating audiences, Live Art breaks the rules about who is making art, how they are making it and who they are making it for.’8 Through its direct concern with space-time politics, it exemplifies anatopism. Keidan goes on to note that ‘live art is synonymous with practices and approaches that cannot be accommodated or placed, whether formally, spatially, culturally or critically: practices and approaches that could be understood as being placeless simply because they do not necessarily fit or often belong in the received contexts and frameworks art is understood to occupy.’9 In its evocation of placelessness, live art always operates within the politics of place and belonging.

In this way, I see live art as a question of citizenship or as a mode of understanding belonging and governance, and thus discuss the concept of anatopism through that of artistic citizenship. Defined as an idea that encapsulates the ‘belief that artistry involves civic-social-humanistic-emancipatory responsibilities, obligations to engage in art making that advances social “goods,”’ artistic citizenship refers to artists who perform ‘social responsibilities’ or regard their practice as a form of social service.10 The concept of art that ‘performs a civic function’ is sometimes seen as oxymoronic, since ‘the artist epitomizes unsullied individualism, an inner-directed free spirit who answers to the muse, not to the state,’ whereas citizenship ‘entails group membership with common privileges and obligations conferred from without and regulated by a national government.’11

Artistic citizenship points not only to what artists do as citizens, but also to how they speak to national and city publics. If citizenship is understood to have ‘symbolic importance as a signifier of an inclusive or exclusive understanding of membership and national belonging,’ then it also paradoxically intimates the very opposite of belonging.12 Elsewhere, I question the viability of the nation-state, a violent form of governance in postcolonial Africa.13 Emerging from a brutal and dehumanising colonial process, the ‘nation’ as a form of governance continues to signify dispossession, and has not shown tolerance for transgender and transrace leadership. Indeed, it seems to perpetuate racism, sexism, homo-prejudice and economic inequality. Using Michael Watts’s characterisation of Nigeria’s political economy as ‘nationalist “unimagining”’ rather than an ‘imagined community,’ I argue that new artistic strategies reflect ‘an un-imagining of the national scale [where] the formulation of citizenship becomes dislocated from the national scale.’14 This has been a difficult argument to make because it raises a question for which I have no answer: what would the alternative be to current nation-states as forms of governance?

I propose a shift away from the conventional definition of artistic citizenship as art serving to fulfil social responsibilities. Rather, I use it here as a way to describe how live art in urban spaces operates in contexts of social fragmentation, creating situations that draw attention to the habitus of social segregation and continued processes of displacement and dehumanisation. In South Africa, race and racialisation remain symptomatic of social breakdown and the continued obscene consumption of the violated, un-homed, un-citizened body. In the interventions that I focus on, live art as social practice is not only a way of performing new norms of citizenship, but it also pries open the transgressive practices of citizenship that constitute different forms of publicness. The public appearances, public performances and public engagements of live art reveal the raced and gendered body as it announces, renounces, uncovers and challenges Eurocentric market-driven definitions of belonging to place.

As a term, anatopism was used by the ‘French doctor Paul Courbon in 1937 … to describe some psychological problems encountered by a Russian living in France, whose uprooting and foreignness prevented him from adjusting to his new environment.’15 In this chapter, I use the concept with reference not to persons, but to the psychosis of the post-1994 city. Anatopism manifests, I argue, in the systemic economic strategies that cement racial and economic segregation. Live art interventions in Cape Town are seldom about public gatherings or establishing public common ground, but operate in factious, unsettled and incongruent arenas of still-segregated urban South Africa. They explode the post-1994 utopian rhetoric of uniformed public space in order to reveal its destructive aspects.

In the analysis of the selected live art interventions, anatopism therefore defines two seemingly contradictory processes. Firstly, it can be seen to define the character of postapartheid cities, which are made up of incongruent architecture modelled after European cities. Neoclassical architecture, for example, reinforces the spatial politics of racial and class division through which the poor are systematically displaced. Secondly, anatopism arises as a political strategy that artists use to challenge this incongruence by, for example, creating situations in which the township is juxtaposed with the city centre. This artistic strategy counteracts the perception of the township as existing at the margins of the city, where all that is associated with it is regarded as out of place in the urban sphere. As a strategy, anatopism reveals the central place of the township in cities (as Mbongwa’s work illustrates) through the exploitative labour system, which causes township residents to be constantly present in the city but never to belong.

Using the first definition, Cape Town’s social processes can be characterised as anatopic. Praised as the ‘European city in Africa’ or, as Valerie Geselev asserts, as ‘a European boil on the bottom of the black continent,’ Cape Town is incongruous for most black South Africans who live in or visit it.16 Spellbound in hyperaesthetic spectacular wealth and scenic fantasy, the city suppresses its nefarious character and its schizoid blunted emotions toward catastrophes of cage-like social segregation.17 Extending this idea, my analysis takes into consideration that live art as artistic citizenship can be seen to redefine notions of the body, senses of belonging and shifting political communities.

Figure 1.1. Buhlebezwe Siwani and Chuma Sopotela, Those Ghels, 2017.

Courtesy Institute for Creative Arts. Photograph by Ashley Walters.

Figure 1.2. Buhlebezwe Siwani and Chuma Sopotela, Those Ghels, 2017.

Courtesy Institute for Cr...