![]()

PART I

Commodification

![]()

ONE

The Pearl Commodity Chain, Early Nineteenth Century to the End of the Second World War

Trade, Processing, and Consumption

WILLIAM G. CLARENCE-SMITH

THE POTENTIAL PROFITS to be made in pearls attracted the attention of the booming West. Natural pearls suitable for jewelry only occurred in very few molluscs, whether saltwater or freshwater. Their high price stimulated experiments in aquaculture from the 1890s, through both farming and artificially seeding molluscs. These trials came to fruition, mainly in Japan, in the interwar years.

Pearls remained for the most part an Asian business, which long displayed marked premodern features. Asian artisans continued to dominate processing, serving a luxury market that was still largely situated in Asia. Asian diasporas effectively resisted competition in marketing from mainly Jewish Western networks. Japanese entrepreneurs received a boost from the emergence of cultured pearls, although this was a markedly more modern business.1

THE GLOBAL TRADE IN PEARLS

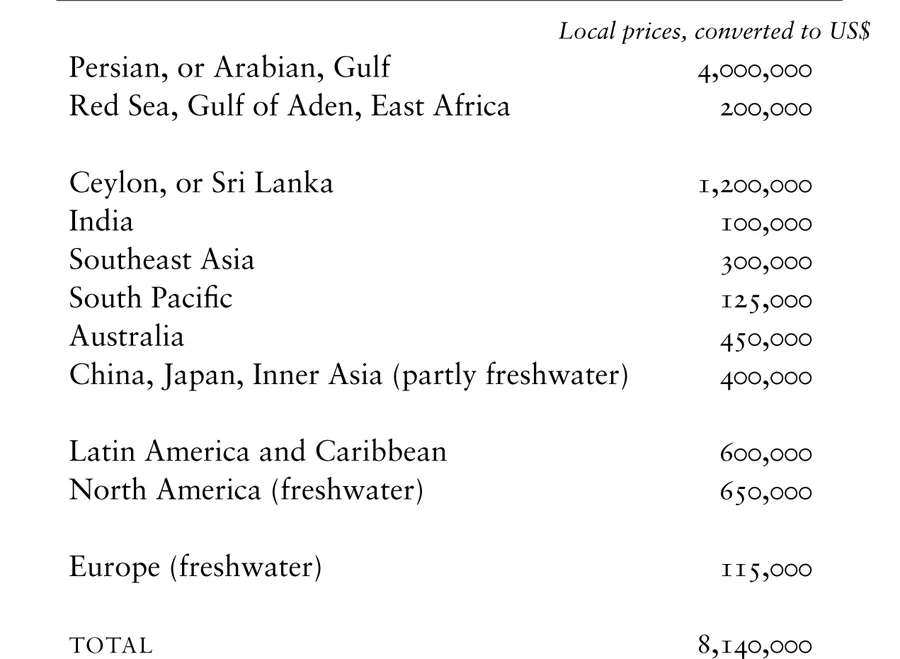

Statistical information for pearls is poor, as they were easy to conceal and often untaxed, so that transactions bypassed official channels.2 Scholars have generally relied on the estimates given by Kunz and Stevenson for 1906 (table 1.1), though these figures probably underestimate the value of freshwater pearls destined for Chinese and Russian markets.

Table 1.1. Estimated value of world output of pearls in 1906

(Source: Kunz and Stevenson, Book of the Pearl, 80)

Asia, including the Middle East, probably remained the largest market for pearls of gem quality throughout the period.3 Demand was enhanced because wealthy elites of both sexes wore pearls.4 Many Asian consumers at this time preferred golden colors, whereas Europeans tended to go for white shades.5

Descriptive evidence repeatedly portrays South Asia as the great global sink for pearls, right through to the Second World War.6 Initially, the chief mart was the Gujarati port of Surat, but newly founded Bombay (Mumbai) had become the prime center by the 1830s.7 Bombay not only imported pearls, but also processed and redistributed them, within India and far beyond.8 India even imported freshwater pearls from Europe and North America, typically small, cheap specimens. As such, they served to embellish embroidery, and, crushed, they were consumed for medicine or added to betel quids for chewing.9

Other Asian lands imported significant quantities. China relied chiefly on its own saltwater and freshwater output.10 However, the empire also imported marine pearls from Japan, the South Pacific, Australia, Southeast Asia, and India, many of the latter being re-exports from the Middle East.11 Persia (Iran), with its close cultural ties to India, stood out among Middle Eastern buyers.12 The Ottoman Empire and its successor states were also significant purchasers.13

Nevertheless, the consumption of pearls in the West was probably growing faster. Stimulated by role models such as Empress Eugénie in France and Queen Victoria in Britain, women’s necklaces were to the fore.14 Unlike in previous centuries, however, Western men at best wore few and small pearls to avoid being perceived as effeminate.15 As pearl prices rose to giddy heights in the early twentieth century, accumulated stocks were released onto Western markets. Owners in Asia, Latin America, and peripheral parts of Europe obtained up to twenty times the purchase price of their gems.16 Most famously, many of the Ottoman imperial family’s jewels were sold at auction in Paris in 1911.17

Western pearl marts shifted in the nineteenth century, away from Seville, Lisbon, Venice, Amsterdam, Vienna, and Leipzig.18 Initially, London enjoyed a major advantage through its imperial connections.19 However, it was Paris, the fashion capital of the West, which gradually established itself as the premier center for pearls.20 Russia remained a largely self-contained market for its own freshwater pearls, centered on Saint Petersburg, until the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.21 New York’s role grew from the 1880s, reflecting the increasing wealth of the United States.22 Indeed, New York took center stage during the First World War and kept a significant part of the business thereafter, although London and Paris recovered to some degree in the interwar years.23

From 1914 to 1945, the world pearl market became more volatile and less profitable. The First World War almost closed down European markets, although demand in the United States persisted.24 A “democratization” of consumption occurred in the 1920s, stimulated by the availability of cheaper Japanese cultured pearls.25 But the Great Depression and the Second World War were periods of severe slump.26

THE PROCESSING OF PEARLS

Tasks were overwhelmingly carried out by hand, and some required very high levels of skill. Pearls needed to be cleaned, dried, sorted, and sometimes peeled or cut to remove imperfections. Color might be enhanced or altered, though this was frowned upon, before polishing and matching by size and color. Some pearls were drilled right through and strung and knotted for necklaces, with clasps added. Others were partly drilled, or left whole, and set in jewels. The risks were immense, especially when peeling or drilling valuable specimens, which could be destroyed by one false move.27

Asian artisans continued to carry out many of these operations, exporting semi-processed or finished goods to the West.28 Jain and Hindu Vaniya “of the poorer class” specialized in such work in Bombay.29 They employed “fine bow-drills” to pierce the pearls.30 Drilling was more expertly done in India than in the West, with straighter and narrower holes.31 Even Venezuelan wholesalers sent pearls to India for drilling and stringing in the 1930s, partly for cost reasons.32 Bombay, the great center for this kind of work, exported both strung bunches and finished necklaces.33 Much processing was also carried out on the Sri Lankan coast.34 “A troop of Indian artisans” who charged “moderate” fees arrived annually to carry out this work.35 Artisans were not only in ports. In Hyderabad, inland in the lands of the Nizam in southern India, pearl processing dated from the eighteenth century.36

For all that, Sugata Bose wrongly repeats an allegation in a Gulf report that drilling was “an Indian monopoly.”37 Chinese workers were reputed to drill even smaller holes than their Indian colleagues, at least in half-pearls.38 However, the Chinese practice of drilling twin holes to sew pearls onto garments was not appreciated in Western markets.39 Kobe workers also drilled and strung pearls.40. Although Bose contends that drilling was not carried out in the Middle East, a Jeddah artisan was reported to be making pearl necklaces in 1858.41

Other processing also occurred outside South Asia, with Canton as the center in China.42 Chinese artisans often set undrilled pearls in jewels, with clasps.43 Expatriate Chinese also peeled pearls in Sulu.44 A Kobe entrepreneur, Todo Yasui, pioneered a new technique to bleach pearls, imparting the whiteness desired by some customers.45

Mikimoto Kokichi, the leading seller of cultured pearls, even established factories. From around 1908, one in Tokyo made jewelry for his Ginza store. By 1911 it employed sixty-five workers, and it was subsequently enlarged.46 Mikimoto also had a pearl factory in Toba by the 1930s “for sorting, drilling, and stringing into necklaces,” partly for export.47 However, processes in these factories are not described in available sources, and they may have consisted of collections of artisans under one roof.

Processing in the West was essentially artisanal.48 This was especially true of the luxury trade. Some machines were used for demi-luxe products, but more for treating metals than gems.49 Although mechanical drills could pierce an average of fifteen hundred pearls per day, compared to an artisan’s forty to fifty, they were little used.50 Jacques Bienenfeld, a major trader in pearls, invented a drilling machine in Paris, but apparently with indifferent success.51

Skilled artisans remain shadowy figures. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, m...