![]()

1

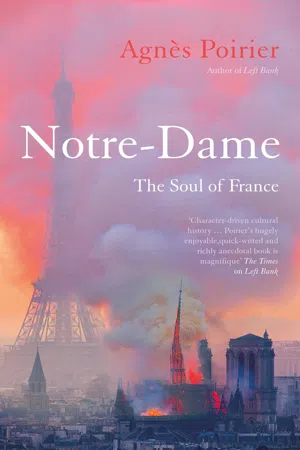

15 April 2019

The Night of the Fire

April in Paris.

The last few days have been blissful: unadulterated blue skies, chestnut and cherry trees in full blossom, an explosion of colours, bright yellow and pink waves rippling down from the heights of Montmartre to the leafy boulevards of Montparnasse, from the Tuileries Gardens at the bottom of the Champs-Élysées to the little park of Notre-Dame cathedral, where children from the neighbourhood love to play after school. This is Monday 15 April 2019, the beginning of Easter week, and those little Parisians are looking forward to their fortnight of spring holiday starting on Friday. That, and egg-hunting.

In the morning, the Cannes Film Festival unveiled the poster for its seventy-second season, taking place a month later. It is always an event. This year it features a young Agnès Varda, the French director who has recently died at the age of ninety. Perched on the back of a male technician, the 26-year-old gamine puts her eye to a camera set perilously high on a wooden platform while in the background the Mediterranean scintillates in the sun. The original black-and-white photograph from 1955 has been ‘colourized’ bright orange. It is a magnificent ode to cinema and to the wonderful director.

Paris is also bristling with expectation, of a political nature. Tonight at 8 p.m. the French president, Emmanuel Macron, will address the nation and hopefully put an end to the weeks of unrest unleashed by the Gilets Jaunes’ polymorphous and radical protest. There have been twenty-two consecutive Saturdays of demonstrations throughout France, bringing havoc and destruction to some city centres, including Paris; and if the movement has by now mostly discredited itself through its casual violence and inability to express a coherent message, the French still want their president and his government to come up with proposals that will bring a sense of closure to the nation.

French political pundits and international correspondents have been trying to figure out what ‘big’ measures Emmanuel Macron might be about to announce, especially since he has already met most of the Gilets Jaunes’ early demands – including the scrapping of fuel tax. One rumour circulates among political journalists: the president might choose to close down the ENA (École Nationale d’Administration), the famous elite school founded in 1945 by Charles de Gaulle to train the country’s highest civil servants. This would indeed be momentous news. Conceived as a democratic recruitment system for the civil service through its exacting exams, the ENA has for a long time been synonymous with French meritocracy. Its students, for instance, never depend on their families to fund their education; instead, the state pays them a salary throughout their studies. However, over the years the school has been criticized for conditioning a pensée unique (one-track thinking), instilling in the future elite a rigid way of looking at the role of the state and the world.

On the Île de la Cité, one of the two small islands at the heart of the French capital, ‘the head, the heart and the marrow of Paris’,1 as it was already known in the twelfth century, the cathedral’s bells are about to ring for vespers. It is 5.45 p.m. and parents are gathering in front of the local primary school gates, waiting for their children to come out, sweaty and dishevelled. On place Maubert, a small square ensconced on boulevard Saint-Germain parallel to Notre-Dame’s south rose window, the bakery Chez Isabelle, which scooped Paris’s ‘best croissant’ and ‘best apple tart’ prizes the previous year, is well prepared for the imminent onslaught of little gourmands and their parents. The lucky ones will be granted a late goûter of pain au chocolat while their parents buy the evening baguette, preferably from the latest batch, still warm from the oven. Next door Laurent Dubois, master fromager (cheese-maker), is also ready. The pre-dinner buying rush is a well-known fixture of Parisian life. ‘Have you bought the bread?’, followed by ‘Do we have any cheese?’, are probably the sentences most commonly uttered in Paris every day between 6 p.m. and 8 p.m.

It has become a daily ritual: a dozen American tourists and their guide, who specializes in gastronomic tours of the French capital, have gathered in front of Laurent Dubois’ round glass domes, which exhibit his latest cheese creations – quince Roquefort, calvados Camembert, walnut Brie, among others. The group is given a mini-lecture on cheese before being invited to step into the shop for tasting and purchasing. Parisians have grown accustomed to living their daily lives among an ever-growing number of such visitors. Mass tourism has transformed many parts of Paris such as this one – place Maubert, the Left Bank and the vicinity of Notre-Dame – into what sometimes feels like a permanent beehive. It has its downside, of course, but Parisians and tourists share at least one thing: their love of Paris. A communion of spirit.

Inside Notre-Dame cathedral, a similar friendly co-existence prevails. On this Monday afternoon, while Canon Jean-Pierre Caveau, helped by the soprano Emmanuelle Campana and the organist Johann Vexo, leads vespers in the nave, hundreds of tourists wander quietly in the aisles and ambulatory. With fourteen million visitors in 2018, Notre-Dame is one of the most popular monuments in the world. Open every day of the year, free of charge, it offers two thousand Masses and celebrations annually.2

The countdown to Easter has started. The priest is reading Psalm 27:

At 6.18 p.m. a fire alarm rings and a message flashes on the cathedral security guard’s computer screen: Zone nef sacristie (Nave sacristy zone), except there is no fire in the sacristy, the small building on the south flank of the cathedral. The guard, who has only been doing the job for a couple of days and hasn’t been told that the fire-alert messaging system is particularly arcane and that the zones are vague, naturally concludes it is a false alarm. There have been a few of them lately, especially since the beginning of important restoration work to the spire, which is now covered with a giant metallic lacework of scaffolding. At 6.42 p.m. a second fire alarm rings.

A few minutes later, Monsignor Benoist de Sinety, the vigorous and youthful-looking 50-year-old vicar-general of the archdiocese of Paris, leaves his residence on rue des Ursins, a medieval street near the cathedral once called rue d’Enfer (Hell Street), and jumps on his scooter. Heading towards the church of Notre-Dame-des-Champs on boulevard Montparnasse for an evening of prayers, Monsignor de Sinety zips through the narrow streets of the island encircling the cathedral, rue Chanoinesse, then rue du Cloître-Notre-Dame, and is about to cross the Seine at pont de l’Archevêché when he briefly looks in his side mirror. He slams on the brakes and turns his head towards Notre-Dame. Flames are leaping out of the cathedral’s roof.3

*

The first call to the fire brigade is logged at 6.48 p.m., four minutes after the guard has finally been told that the fire-alert message indicates the cathedral’s main attic, not the sacristy, and two minutes after he has climbed the 300 narrow steps and opened the door to the inferno already raging. The ‘forest’, Notre-Dame’s latticework roof structure of 1,300 oak beams, most of which date from the thirteenth century, is being consumed alive.

At the Élysée Palace, the president finishes recording his address to the nation while French TV channels are busy preparing special editions to comment on his announcements. Not for long. Pictures and videos taken by passers-by, first of black smoke coming out of the spire, then of orange and red tongues of fire licking at the sky, are proliferating on social networks.

Exactly 19 kilometres away Marie-Hélène Didier, a National Heritage curator in charge of France’s religious art, and Laurent Prades, Notre-Dame’s general manager, have just arrived in Versailles; they are attending the reopening of Madame de Maintenon’s royal apartment at the palace. Franck Riester, France’s culture minister, is also there. After three years of painstaking restoration work, the four beautiful rooms where Louis XIV’s secret wife lived between 1680 and 1715 are about to open to the public. Champagne hasn’t yet been served when mobile phones start vibrating in guests’ pockets. Madame de Maintenon and Versailles will have to wait.4

With one hand fumbling in her bag for her car key, Marie-Hélène Didier immediately calls Philippe Villeneuve, a chief architect at Historic Monuments, one of thirty-nine responsible for France’s architectural heritage, each of whom looks after a portfolio of important buildings. In 1893, the Department of Historic Monuments started recruiting the most gifted art historians and architects of their generation through a series of thorough and demanding tests.5 ‘To keep a historic monument alive in our present times requires erudition, talent, respect, discretion and moral qualities.’6 They are France’s elite architectural corps.

Notre-Dame belongs to Philippe Villeneuve. Or rather, Philippe Villeneuve belongs to Notre-Dame. As a small boy with a passion for organ music, he found his vocation in architecture while seated on the wooden benches of the cathedral, listening for hours to Pierre Cochereau, Notre-Dame’s legendary organist,7 improvising on one of the world’s largest organs, with 5 manuals, 111 stops and 7,374 pipes.8

Philippe Villeneuve is in the Charentes region, in the south-west of France, and is already driving at 180 km/h to the nearest train station, La Rochelle.9 Marie-Hélène Didier, now too in her car, has clearly made the wrong decision. She is soon stuck in traffic on Paris’s Right Bank, between the Louvre and the Hôtel de Ville, and all she can do is switch off both the radio and Twitter and watch, feeling completely powerless. Notre-Dame is in flames right in front of her.

Fortunately, Laurent Prades has opted for public transport and hopped on the RER, the regional line to Paris from Versailles. The fastest train takes fifty-eight minutes. Saint-Michel-Notre-Dame station has just been closed, though, and he must exit at Musée d’Orsay. He will have to finish his journey by bike: luckily he owns a pass for the Vélib’ public cycle-sharing scheme which allows him to use any of the freely available bicycles found at docks on every Paris street corner. He will then need to get through police lines as fast as he can. As general manager of the cathedral he is not only in charge of its sixty employees but he also knows where the keys are – all 100 of them. He knows every code too, including those of Notre-Dame’s treasury and another discreet safe placed in the chapel called Notre-Dame des Sept Douleurs (Mater Dolorosa), at the far end of the cathedral, right behind the apse. In this double-bulletproof-glass safe lies the crown of thorns. Cycling towards the cathedral under a rain of ashes and fiery flakes, the 42-year-old Laurent Prades has one obsession: to save the Catholic world’s most precious religious relic from destruction.

*

‘The guilt,’ says Jean-Claude Gallet, three-star general, veteran of Afghanistan and commander-in-chief of the Paris fire brigade, ‘the guilt is overwhelming. How could we have arrived when the fire had already spread so dramatically? Did our switchboard miss a call?’10 In fact, the firemen haven’t failed and haven’t missed any calls. And it takes them only a few minutes to arrive after the first call, but it does indeed already appear too late to save Notre-Dame’s 800-year-old roof.

General Gallet knows about fire, all kinds of fire. After graduating from the elite mi...