![]()

1

Introduction

The purpose of this book is to help you improve your ability to solve mathematical, scientific, and engineering problems. With this in mind, I will describe certain elementary concepts and principles of the theory of problems and problem solving, something we have learned a great deal about since the 1950s, when the advent of computers made possible research on artificial intelligence and computer simulation of human problem solving. I have tried to organize the discussion of these ideas in a simple, logical way that will help you understand, remember, and apply them.

You should be warned, however, that the theory of problem solving is far from being precise enough at present to provide simple cookbook instructions for solving most problems. Partly for this reason and partly for reasons of intrinsic merit, teaching by example is the primary approach used in this book. First, a problem-solving method will be discussed theoretically, then it will be applied to a variety of problems, so that you may see how to use the method in actual practice.

To master these methods, it is essential to work through the examples of their application to a variety of problems. Thus, much of the book is devoted to analyzing problems that exemplify the use of different methods. You should pay careful attention to these problems and should not be discouraged if you do not perfectly understand the theoretical discussions. The theory of problem solving will undoubtably help those students with sufficient mathematical background to understand it, but students who lack such a background can compensate by spending greater time on the examples.

SCOPE OF THE BOOK

This book is primarily a practical guide to how to solve a certain class of problems, specifically, what I call formal problems or just “problems” (with the adjective formal being understood in later contexts). Formal problems include all mathematical problems of either the “to find” or the “to prove” character but do not include problems of defining “mathematically interesting” axiom systems. A student taking mathematics courses will hardly be aware of the practical significance of this exclusion, since defining interesting axiom systems is a problem not typically encountered except in certain areas of basic research in mathematics. Similarly, the problem of constructing a new mathematical theory in any field of science is not a formal problem, as I use the term, and I will not discuss it in this book. However, any other mathematical problem that comes up in any field of science, engineering, or mathematics is a formal problem in the sense of this book.

Problems such as what you should eat for breakfast, whether you should marry x or y, whether you should drop out of school, or how can you get yourself to spend more time studying are not formal problems. These problems are virtually impossible at the present time to turn into formal problems because we have no good ways of restricting our thinking to a specified set of given information and operations (courses of action we might take), nor do we often even know how to specify precisely what our goals are in solving these problems. Understanding formal problems can undoubtedly make some contributions to your thinking in regard to these poorly specified personal problems, but the scope of the present book does not include such problems. Even if it did, it would be extremely difficult to specify any precise methods for solving them.

However, formal problems include a large class of practical problems that people might encounter in the real world, although they usually encounter them as games or puzzles presented by friends or appearing in magazines. A practical problem such as how to build a bridge across a river is a formal problem if, in solving the problem, one is limited to some specified set of materials (givens), operations, and, of course, the goal of getting the bridge built.

In actuality, you might limit yourself in this way for a while and, if no solution emerged, decide to consider the use of some additional materials, if possible. Expanding the set of given materials (by means other than the use of acceptable operations) is not a part of formal problem solving, but often the situation presents certain givens in sufficiently disguised or implicit form that recognition of all the givens is an important part of skill in formal problem solving. That skill will be discussed later.

Practical problems or puzzles of the type we will consider differ from problems in mathematics, science, or engineering in that to pose them requires less background information and training. Thus, puzzle problems are especially suitable as examples of problem-solving methods in this book, because they communicate the workings of the methods most easily to the widest range of readers. For this reason, puzzle problems will constitute a large proportion of the examples used in this book—at least prior to the last chapter.

In principle, it might seem that most important problem-solving methods would be unique to each specialized area of mathematics, science, or engineering, but this is probably not the case. There are many extremely general problem-solving methods, though, to be sure, there are also special methods that can be of use in only a limited range of fields.

It may be quite difficult to learn the special methods and knowledge required in a particular field, but at least such methods and knowledge are the specific object of instruction in courses. By contrast, general problem-solving methods are rarely, if ever, taught, though they are quite helpful in solving problems in every field of mathematics, science, and engineering.

GENERAL VERSUS SPECIAL METHODS

The relation between specific knowledge and methods, on the one hand, and general problem-solving methods, on the other hand, appears to be as follows. When you understand the relevant material and specific methods quite well and already have considerable experience in applying this knowledge to similar problems, then in solving a new problem you use the same specific methods you used before. Considering the methods used in similar problems is a general problem-solving technique. However, in cases where it is obvious that a particular problem is a member of a class of problems you have solved before, you do not need to make explicit, conscious use of the method: simply go ahead and solve the problem, using methods that you have learned to apply to this class. Once you have this level of understanding of the relevant material, general problem-solving methods are of little value in solving the vast majority of homework and examination problems for mathematics, science, and engineering courses.

When problems are more complicated, in the sense of involving more component steps, and are not highly similar to previously solved problems, the use of general problem-solving methods can be a substantial aid in solution. However, such complex problems will be encountered only rarely by the beginning mathematics, science, and engineering students taking courses in high school and college. More important to the immediate needs of such students is the role of general problem-solving methods in simple homework and examination problems where one does not completely understand the relevant material and does not have considerable experience in solving the relevant class of problems. In such cases, general problem-solving methods serve to guide the student to recognize what relevant background information needs to be understood. For example, when one understands the general problem-solving method of setting subgoals, one can often set particular subgoals that directly indicate what types of specific information are being tested (and thereby taught) by a particular problem. One then knows what sections of the textbook to reread in order to understand the relevant material.

If, however, the book is not available, as in many examination situations, general problem-solving methods provide one with powerful general methods for retrieving from memory the relevant background information. For example, the use of general problem-solving methods can indicate for which quantities one needs a formula and can provide a basis for choosing among different alternative formulas. Frequently, a student may know all the definitions, formulas, and so on, but not have strong associations to this knowledge from the cues present in each type of problem to which this knowledge is relevant.

With experience in solving a variety of problems to which the knowledge is relevant, one will develop strong direct associations between the cues in such problems and this relevant knowledge. However, in the early stages of learning the material, a student will lack such direct associations and will need to use general problem-solving methods to indicate where in one’s memory to retrieve relevant information or where in the book to look it up. Assuming this idea is true (and this book aims to convince you it is), mastering general problem-solving methods is important to you both so you can use problems as a learning device and so you can achieve the maximum range of applicability of the knowledge you have stored in mind—on an examination, on a job, or whatever.

The goal of this book is to teach as many of these general problem-solving methods as I know about, so that if you spend the time to master these methods you can more effectively learn the subject matter of your courses. Also, since the ability to use the information given in most mathematics, science, and engineering courses is often primarily the ability to solve problems in these fields, the book aims to increase this ability to use knowledge.

RELATION TO ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

It should be emphasized that this text is primarily a practical how-to-do-it book in a field where the level of precise (mathematical) formulation is far below what I am sure it will be in the future, perhaps even the near future. Artificial intelligence and computer simulation of human problem solving are currently very active fields of research, and results from some of this work have heavily influenced this book. However, theoretical formulations of problem solving superior to those we currently have will eventually make the present formulation outdated. Nevertheless, the methods described in the present book, however imperfectly, can be of substantial benefit to any student who masters them. When someone has a beautiful mathematical theory of problems and problem solving sometime in the future, then clearer and more effective how-to-do-it books can be written. Meanwhile, it is my hope that this book will help many people to solve problems better than they did before.

APPLYING METHODS TO PROBLEMS

As discussed previously, to master the problem-solving methods described in this book, it is necessary to study the example problems illustrating their use. The problems and solutions analyzed in Chapters 3 to 10 illustrate the use of the methods discussed in the particular chapter. Chapter 11 considers a variety of homework and examination problems for mathematics, science, and engineering courses. Of course, you probably have lots of your own problems to solve in school or work, and you should begin using the methods on these problems immediately. Merely reading this book provides only the beginning concepts necessary to mastering general problem-solving methods. Practice in using the methods is essential to achieving a high level of skill.

Everyone who solves problems uses many or all of the methods described in this book, but if you are not an extremely good problem solver, you may be using the methods less effectively or more haphazardly than you could be by more explicit training in the methods. At first, the application of such explicitly taught problem-solving methods involves a rather slow, conscious analysis of each problem.

There is no particular reason to engage in this careful, conscious analysis of a problem when you can immediately get some good ideas on how to solve it. Just go ahead and solve the problem “naturally.” However, after you solve it or, even better, while you are solving it, analyze what you are doing. It will greatly deepen your understanding of problem-solving methods, and you might discover new methods or a new application of an old method.

As you get extensive practice in using these problem-solving methods you should become so skilled in their use that the process becomes less conscious and more automatic or natural. This is the way of all skill learning, whether driving a car, playing tennis, or solving mathematical problems.

![]()

2

Problem Theory

FOUR SAMPLE PROBLEMS

To illustrate the concepts involved in the theory of problems described in this chapter, we will begin with four sample problems.

Instant Insanity

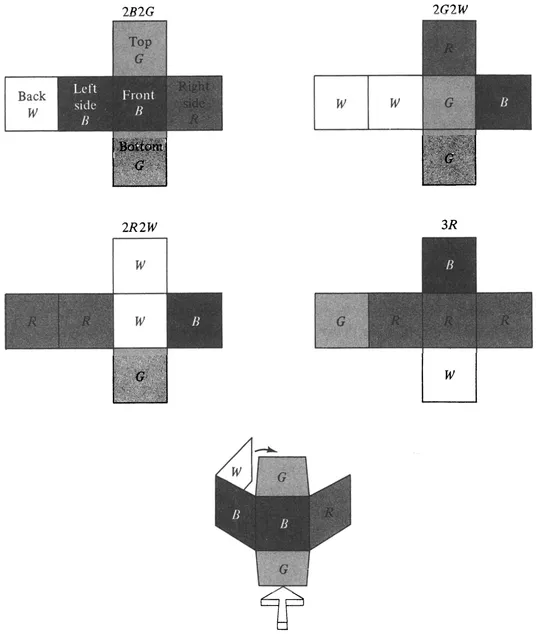

Instant Insanity is the name of a popular puzzle consisting of four small cubes. Each face of every cube has one of four colors: red (R), blue (B), green (G), or white (W). Each cube has at least one of its six faces with each of the four different colors, but the remaining two faces necessarily must repeat one or two of the colors already used.

The exact configurations of colors on the faces of the cubes are shown in Fig. 2-1. The faces of the cubes in the figure have been cut along the edges and flattened out for easy presentation on the two-dimensional page. (To reconstruct the cube in three-dimensions, one would simply cut out the outlined figure, turn the top flap over on the top and the bottom over on the bottom, and wrap the left side and back around to join up with the right side at the rear of the cube.) For convenience, the faces of one cube in the figure have been labeled front, top, bottom, back, left side, right side. If you think of the front cube as being closest to you (facing you), then mentally constructing the cube from the two-dimensional drawing should be relatively easy to do. However, you may wish to buy the puzzle to provide a more concrete and enjoyable representation.

FIGURE 2-1

The six colored faces of each of the four cubes in the Instant Insanity puzzle. You could cut out each of the above figures and fold along the edges to make cubes. In the above figure R = red, B = blue, W = white, and G = green. The cubes have been given these “names”: 2B2G, 2G2W, 2R2W, and 3R, which indicates the colored faces, of which they have more than one.

The goal of the puzzle is to arrange the cubes one on top of the other in such a way that they form a stack four cubes high, with each of the four sides having exactly one red cube, one blue cube, one green cube, and one white cube.

Chess Problem

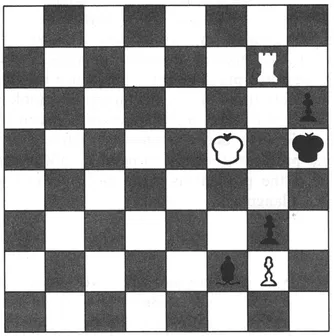

From the board configuration shown in Fig. 2-2 describe a sequence of moves such that white can achieve mate in five moves.

Find Problem from Mechanics

What constant force will cause a mass of 3 kilograms to achieve a speed of 30 meters per second in 6 seconds, starting from rest?

Proof Problem from Modern Algebra

You are given a mathematical system consisting of a set of elements (A, B, C), with two binary operations (call them addition and multiplication ) that combine two elements to give a third element. The system has the following properties: (1) Addition and multiplication are closed; that is, A + B and A Bare members of the original set for all A and B in the set. (2) Multiplication is commutative; that is, AB equals BA for all A and B in the set. (3) Equals added to equals are equal; that is, if A = A’ and B = B’, then A + B = A’ + B’, for all A, B, A’, B’ in the set. (4) The left distributive law applies; that is, C(A + B) = CA + CB, for all A, B, C in the set. (5) The transitive law also applies; that is, if A = B and B = C, then A = C. From these given assumptions, you are to prove the right distributive law—that is, that (A + B)C = AC + BC, for all A, B, C in the set.

FIGURE 2-2

Part of a famous chess problem. White to achieve mate in five moves.

WHAT IS A PROBLEM?

All the formal problems of concern to us can be considered to be composed of three types of information: information concerning givens (given expressions), information concerning operations that transform one or mo...