![]()

Chapter 1

Shanta Apte and the unexpected

Anupama Kapse

Shanta sings

With their enhanced realism, talkies sealed the fate of male actors who played female parts on stage and in early Indian silents. The Gandharva Natak Mandali, which established Bal Gandharva as a celebrated female performer put up its last show on December 31, 1934 (Nadkarni 1987: 111). By the 1930s, educated young women from high-caste, high-class families broke the taboo on acting and became key attractions of the talkies. Women such as Durga Khote were given top billing in both advertisements and reviews that began to appear in English language dailies such as The Bombay Chronicle and The Times of India. Along with journals such as Filmland and Film India, newspapers that covered mostly political events began to include regular columns on major studios such as Prabhat, New Theatres and Bombay Talkies. Stars such as Devika Rani (Bombay Talkies) and features such as Devdas (P. C. Barua, 1935, New Theatres) were of particular interest. A Times of India review applauds Durga Khote’s work as Saudamini, pirate queen of Prabhat’s Amar Jyoti/The Eternal Flame (1936), thus: she ‘gives to the picture its strong virility. … She speaks and acts with appropriate force and dignity’ [my emphasis] (Anon. 1936: 7).

Durga Khote’s own role model, the celebrated male actor Bal Gandharva was, however, known for being far more feminine in his theatrical performances. His ‘seductive’ facial expressions and hand gestures made him a perennial favourite in Goa and Maharashtra during the teens and the twenties. Theatre-goers admired his ivory, ‘porcelain smooth’ hands, their ‘sleek, curved shape [and] … the closing and opening of the actor’s tapering fingers’; the ‘feminine charm’ with which he shook his lower lip (Nadkarni 1987: 93, 100). Khote remembers the ‘indescribable’ beauty of his hands, ‘whether they were carrying a garland at [Rukmini’s] swyamwar, Sindhu’s hands holding the wooden stick of the stone grinding mill, Draupadi’s piteously pleading hands spread before Krishna for help, or even a courtesan’s hands lovingly offering a paan’ (Khote [1976] 2007: 44, cited in Kosambi 2015: 271).

Bal Gandharva went to great lengths to make his female appearances convincing. He would lighten his skin with specially ordered makeup from Max Factor and wear custom wigs designed by an Italian saloon named ‘Fucile’, located in Bombay (Nadkarni 1987: 93). Gandharva’s popularity rested upon the enhancement of femininity, while Khote’s performance was lauded for its regal gravitas, an attribute of male monarchs in traditional theatre. Critics praised her stately, authoritative bearing to the extent that any male actor cast against her risked being overshadowed and needed to differentiate the register of his performance. In Ayodhyecha Raja (V. Shantaram, 1932), Prabhat’s first talkie and Khote’s second, Khote appeared in the role of Queen Taramati. A stage actor named Gole (first name unknown) was initially cast as her husband, the selfless, long-suffering King Harishchandra. Gole found Khote’s proximity so unsettling that he had to be replaced by music director Govind Rao Tembe, a well-known actor and composer who was able to match Khote’s ‘imposing’ stature (Godbole 2015: 71).

Khote was not literally ‘manly’; rather, the talkies’ new patrons were impressed by her muted femininity. In contrast, the extravagant Bal Gandharva once complained about wearing plain cotton saris as his brocades had become unaffordable after Mahatma Gandhi launched his swadeshi campaigns. He began to drench his saris in eau-de-cologne to make them cling to his body (Nadkarni 1987: 80, 99). Meera Kosambi observes that ‘no respectable woman would have draped the sari tightly enough to reveal the contours of her body. … A man dressed as a woman could take liberties that women themselves were not allowed’ (2015: 271). Khote thus embodies the transformations that well-born women underwent when they embraced acting, traditionally a male profession. As a first-generation actress who had crossed over from elite to a relatively mofussil underclass, she was required to ‘dignify’ acting through subtle gradations in screen femininity. She could appear majestic, but if she appeared too feminine she risked travestying the heightened codes of femininity established by male performers.

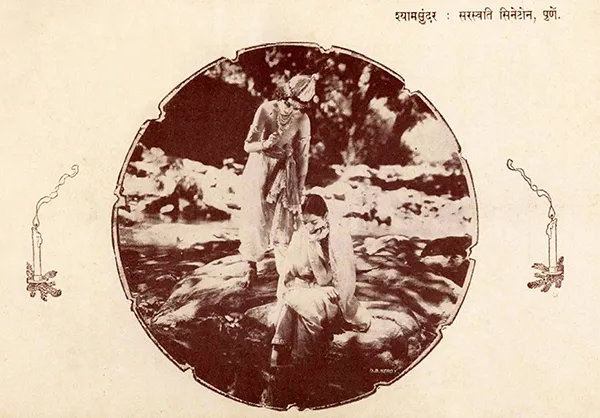

I begin with Khote in an attempt to outline the specific contributions Shanta Apte (1916–1964) made to song performance and acting during this era, as Khote’s contemporary and successor. If Khote was forceful, then her twenty-year-old co-star Apte was ‘captivating’ and ‘enchanting’. Khote excelled at playing a ‘difficult’ role while Shanta Apte was praised for ‘carrying the picture on her shoulders … her singing is … one of the major beauties of [this] production’ (Times of India, 26 June 1936: 7). Apte started her career as a child star in Bhalji Pendharkar’s mythological Shyam Sundar (1932).1 Christian-born Shahu Modak co-starred as Krishna in a joint debut (Figure 1.1). Modak was lauded for his remarkable singing talent while Apte was barely noticed in her first film (South China Morning Post, 10 February 1934: 12). Nevertheless, the picture ran for twenty-five weeks, a record run that echoed the new craze for talkies. It became the first film to add a song sequence by popular demand after its release (Godbole 2015: 51).

Figure 1.1 Shanta Apte and Shahu Modak, pictured together in the booklet for Shyam Sundar (1932). Courtesy of the National Film Archives of India, Pune.

Amar Jyoti established a firm reputation for Shanta Apte as a vivacious singing star. In Rajput Ramani (Keshav Rao Dhaiber, 1936) Apte once again played second lead, this time to Nalini Tarkhad. However, reviews singled Apte out for carrying the film on her shoulders: ‘the picture really belongs to Shanta Apte, who steals it entirely by her vivid personality, her wonderful singing [and] the naïve naturalness of her acting’ (Times of India, 13 November 1936: 9). Elements of her work as a child star were thus recast in the mould of an effervescent child-woman, a trait enhanced by her light singing style. Although she played second lead to Khote in Amar Jyoti, Apte’s virginal charm was widely appreciated in her adult roles (Durga Khote was separated from her husband but was often referred to as ‘Mrs Khote’). If Apte was an ingénue, Khote was admired for her majesterial qualities, which were ‘charming by contrast’ (9): too much sexuality was inadmissible for both. Together both stars personified the complementary elements of screen femininity in the early talkie, of which Amar Jyoti remains the best example (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Durga Khote, Shanta Apte and Vasanthi in Amar Jyoti (1936). Public domain.

To be sure, Apte’s star appeal depended on her ability to sing and act at the same time. Close associate, friend and lyricist Shantaram Athavale describes this transition as one fraught with intense disagreement and doubt. Prabhat’s reputation grew with the success of director V. Shantaram’s early talkies, Ayodyecha Raja/Ayodhya Ka Raja, Jalti Nishani/Agnikankan (Branded Oath, 1932) and Maya Machchindra (Illusion, 1933), which were released in Hindi and Marathi versions. Shantaram started his career as an assistant photographer under the master scenarist Baburao ‘Painter’, who founded the Maharashtra Film Company in Kolhapur in 1929. The Prabhat team included Painter’s disciples V. Damle, who did the sound with a newly bought Audio Camex machine, and S. Fattelal, who designed the massive sets and elaborate costumes. Keshavrao Dhaiber joined Prabhat as the principal cameraman, with Keshvarao Bhole as the music composer. Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen describe the early Prabhat features as neoclassical ([1994] 1999: 178). Themes were drawn from mythological stories and historical epics, while the sets often featured elaborate plaster of Paris statues and columns. The ornamental grandeur of the sets and Shantaram’s astute stewardship were crucial to the studio’s success.

On par with its competitors Bombay Talkies and New Theatres, Prabhat was known for its decorative realism and stylized treatment of nationalist themes, not to mention its reputed actors. Publicity materials describe the 175 feet long, 80 feet broad and 55 feet high studio as a mammoth film city or ‘Prabhat Nagar’ (Times of India, 8 October 1934: 14). Newspapers argued that the talkies ensured a ‘rosy’ and profitable future for Prabhat, which drew large audiences across the country and participated in international film festivals with Amar Jyoti’s release. The studio controlled every aspect of film production including the hiring of stars, distribution and publicity, and agendas that were meticulously documented in deeds and contracts.2 A documentary, Prabhatche Prabhatnagar (V. Shantaram, 1935) was made to promote its films and show off the studio’s state-of-the art cameras, lighting and costume departments, and sets and machinery; attractions displayed to visitors invited to marvel at Prabhat as a ‘museum’ of the talkies.

Amrit Manthan/The Churning of Nectar (V. Shantaram, 1933) was Prabhat’s first major, all-India hit, with Nalini Tarkhad as a just princess who attempts to overthrow a sacrificial cult. Shanta Apte plays her aide: her ghazal ‘Raat aayi hai naya rang jamane ke liye’ (Night fall ushers new colors) attracted large crowds in Punjab, a major centre in the talkie circuit that extended Prabhat’s reach further north to Lahore. Like Bombay Talkies’ founder Himansu Rai, Shantaram visited UFA studios in Germany to supplement the Indian elements gleaned from his guru Baburao Painter. Following this visit, Amrit Manthan marks a distinct shift towards expressionism: Shantaram’s most famous shot is an extreme close up of the ‘eye of evil’ taken with a telephoto lens. Evoking megalomania and tyranny, it doubled as a veiled reference to British colonialism. Audiences went wild for Apte, now hailed as ‘a singing siren’ (Times of India, 7 August 1937: 18), but she would again be cast as second lead to Leela Chitnis in Vahan (Beyond the Horizon, K. Narayan Kale, 1936). Shantaram thought that Apte could sing but had little knowledge of acting, while music director Keshav Rao Bhole felt that her singing style was ‘too classical’. Worse, Keshav Rao Dhaibher, director of Rajput Ramani (Prabhat’s first solo Hindi release) was attracted to Nalini Tarkhad, and favoured her over Apte. In spite of being sidelined, Apte’s songs rescued an otherwise unremarkable film (Athavale 1965: 151).

John Belton has argued that ‘sound recording and mixing lack the authenticity of the photographic image, which guarantees the authenticity of reproduction … The microphone records an invisible world—that of the audible, which consists of different categories of sound—dialogue, sound effects, and music … regularly broken down into and experienced as different elements’ (1985: 64). There are several extant accounts of the frustrations accompanying Prabhat’s attempts to normalize sound. As a hero, Govindrao Tembe did not stop singing while Ayodyecha Raja was being filmed. The camera had to continue rolling (Godbole 2015: 69) until he stopped. When he was finally cast in a male role in Dharmatma (1935), Bal Gandharva could not follow Shantaram’s directions. It was hard to break his performance into shots that broke the linear temporality and continuity of stage performance (Athavale 1965: 135). The audience was invisible. Instead of requests for encores, Gandharva had to contend with demands for retakes. Used to hearing rather than reading prompts, the thespian forgot his lines. More unfortunately, he could not find the right pitch for the microphone as he was partially deaf in one ear (Athavale 1965: 171; Kosambi 2015: 333). The film incurred losses that Amar Jyoti more than made up for.

Upon viewing the rush print of Ayodyecha Raja the day before its release, Damle discovered that the sound was out of sync (Godbole 2015: 68). As in early sound films elsewhere, the Audio Camex equipment picked up far too much ambient sound. Prabhat built a soundproof studio to fix this. Musicians who would sit in front of the stage now sat behind the camera and ‘background’ music was performed onsite so as not to interfere with spoken dialogue. If, as John Belton notes, the coming of sound often ‘bec[a]me unreal in [its] quest for realism’ (1985: 67–68), then there were important differences that revolved around the use of songs in the Indian context. Playback was introduced in 1935 (Pande 2006; Majumdar 2009) but Prabhat stuck to synchronized songs – technically, they were cheaper. Non-naturalistic forms of theatre were slowly being brought in line with fresh conventions of realism as the actor performed without a live audience in front of a camera, microphone and studio technicians. To this end Kunku/The Unexpected/Duniya Na Mane (V. Shantaram, 1937), which I examine in my next section, included a background score that was shot without any musical instruments: sound was produced on the set by props such as cups, clocks and canes, which ...