![]()

1

On a Friday morning in late winter, New Yorkers are fighting the remnants of yet another surprise storm. Trains are delayed, puddles of slush surpass ankles, and umbrellas flip inside out. Yet climbing up the narrow and uneven staircase to a second-floor yoga studio in a former factory building in the Bowery, a loft where Keith Richards once lived, the unpleasantness of the journey is alleviated by the arrival. Inside the airy space, a gray light filters in from three tall windows looking out onto a strip of boulevard, once home to drunks and derelicts, that today boasts athleisure boutiques, juice shops, an upscale organic grocery store, and this establishment, with a cheeky name to acknowledge its singularity: The Studio. What sets this space apart from the innumerable yoga studios in New York City is its unique offering, Katonah yoga, which draws on Taoism and Chinese medicine, and the advanced students who call this studio home. The Studio is, as its website proudly proclaims, “where your teacher comes to practice.”

Despite the slush and snow outside, The Studio’s main teaching salon is packed cheek by jowl with students and their requisite props. A basic Katonah setup includes a mat, two blankets, a long strap for adjustments, four blocks, and a cloth sandbag for weighing down various body parts. Several people have draped themselves over folding chairs in supported backbends, blocks under their heads and their limbs trussed up, a somewhat medieval-looking arrangement reminiscent of the rack. Other students cluster in small groups to laugh and catch up, creating an atmosphere that’s more cocktail party than silent monastery.

Then Abbie Galvin enters the room. A petite sixty-three-year-old with a mop of curly brown hair highlighted with blond streaks, this unassuming yogini in Adidas wind pants and a white boatneck top is the reason the people in this room have braved the morning’s gale-force winds. She got in late last night from a training in LA, where students traveled from as far as Europe to study with her. If she’s tired or jet-lagged, she’s not showing it.

Immediately she starts making adjustments, bringing another block for a fellow who’s upside-down over a chair, and pointing students—many of whom are also Studio teaching staff—to where they can most usefully provide the many hands-on tweaks Katonah yoga is known for.

She notices a newbie, Margo, off in a corner in expensive leggings and a high ponytail—Abbie knows the hundreds of students who are regulars by name and face—and introduces herself. She asks Margo to sit with her feet together to create a diamond shape with her legs, and wraps a strap under her hips. Abbie is reading Margo’s feet, which is something like a palm reading, except where lines might indicate your longevity (or lack thereof) or love life (or lack thereof), the crests and wrinkles of the feet correspond to strengths and weaknesses in the body and their correlative spiritual attributes. The practice comes out of Taoism, but Abbie has made the ancient technique pragmatic.

Abbie translates the lines of Margo’s feet. By now, half a dozen students have gathered around. “See how the ball of the left foot is flatter than the fullness of the ball of the right foot? That means the left lung isn’t getting enough air,” Abbie says. The flatness is the result of a dip in Margo’s hip, itself the product of her organs being “collapsed,” as Abbie terms it, or not functioning at their optimal capacities.

“Ah, that makes sense,” says one of Abbie’s disciples.

“Of course it makes sense,” Abbie jokes. “I’m a person who makes sense!” Her teaching style is more brassy Borscht Belt Joan Rivers than guru en route to nirvana.

Abbie continues diagnosing newbie Margo by placing a tiny foot on her sternum. The woman grows several inches: “Now this is how you plug in, how you rise up, how you put yourself in the center of yourself.”

“Wow, it feels so awkward,” Margo observes.

“Everyone is off-center,” Abbie tells her, along with the several students who are now taking notes. “It’s not pejorative. If something is wrong, it’s just because you don’t know. Now you’ve got lungs, a socket, an antenna,” she says, using the metaphor-heavy language of Katonah. “You’re plugged in. Your job is to reference this idea, instead of just doing you.”

Whereas many yoga teachers will urge students to “listen to their bodies” to find shapes that feel right to them, Katonah stresses objective measurement, using props like blocks and straps to ensure limbs land where they are supposed to. “Freedom is not doing whatever the fuck you want,” Abbie says. “It’s about finding freedom within confinement. It’s about having good boundaries.”

This is all before class has officially begun.

UNLIKE MOST CLASSES, WHERE yogis line up their mats to face the teacher at the front of the room, Katonah students place their mats to face the center. The configuration creates a more communal experience, and Abbie is rarely in one spot for longer than a minute. She commences with a pose recognizable to any lay student of yoga. “Let’s get into a dog,” she says, and the room suddenly quiets. “It’s not the most interesting pose,” she acknowledges with a laugh. “Now get your ass way up!” I giggle. “Now look way out,” she continues. “That’s the way toward your future. Would you rather look at your crotch or into your future?”

Abbie guides us into a modified cat-cow stretch, a gentle undulation of the spinal column. But things get interesting when she asks us to cross our legs behind, and to begin flipping our wrists to “move currency” through the body. “Beautiful, Jonathan!” she shouts across the room to a fellow whose body type is more plumber than yogi. “So nice, Alex!” admiring the form of a Studio teacher with triceps sharp like knives.

In Abbie’s classes, students hold poses for much longer than the typical few breaths, although Abbie would likely quibble with my phrasing. “You don’t hold poses,” I hear her explain from across the room. “You move currency through forms. You orient yourself.” She urges us to find the balance between exertion and punishment: “You don’t drive until you run out of gas; you drive until you reach your destination.”

In a particularly pretzely forward fold, where we swim our arms to grab opposite ankles, a regular, Harry, shouts, “This is hard!”

“Life is hard,” Abbie claps back. “You could look a little happier!” Toward the end of class, she tells us to bring our mats to the wall to use the hard surface behind us as leverage to go deeper into a lunge known as pigeon pose. “But don’t take all day!” she shouts with a smile as we find ourselves new spots. The laughter breaks through the sound of weary breathing.

Abbie’s gift is seeing the wonkiness that resides in all bodies. She can spot a wrinkle in the neck or a torqued hip from across the room. She often demonstrates proper alignment on individuals, wrapping her ubiquitous strap around a waist and placing a foot into the crook of a hip to magically imbue the person with more inches and internal space, as a small cabal of teachers and seasoned students forms around her to watch. At one point, she walked all 105 pounds of her body up a gentleman’s back. Her classes are more of a workshop than a traditional flow, and devotees come not only to work up a sweat but to gain knowledge of her philosophy, both in theory and in how it manifests in the body.

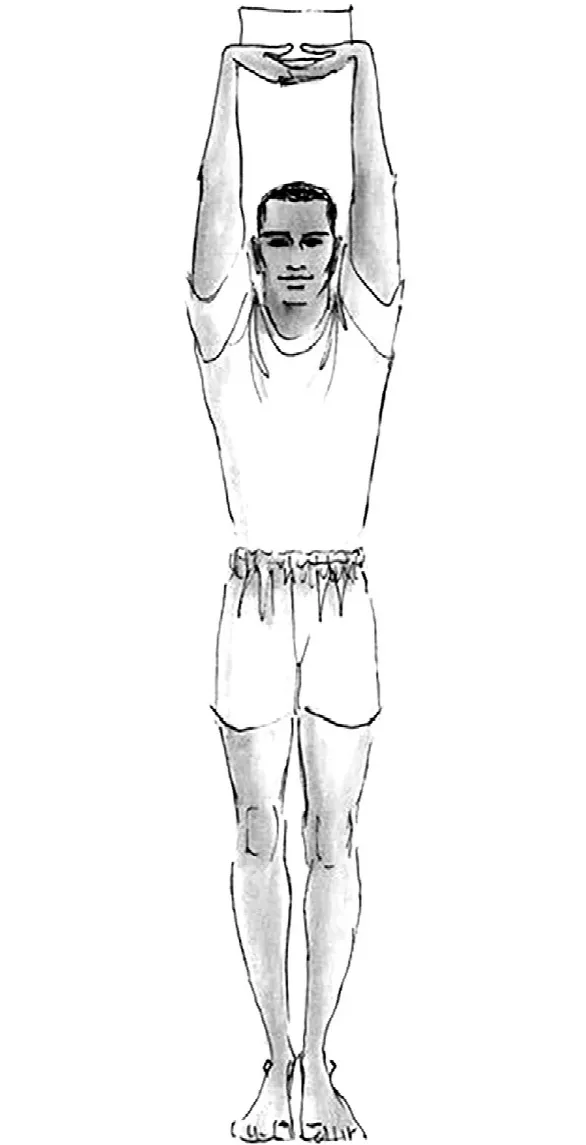

Abbie’s microscopic attention to detail cuts both ways. Toward the class’s close, she readies us for King of the Mountain, a pose where you interlace your fingers, palms up, and hold your arms above your head for a full nine minutes with a yoga block balancing on your palms, “your crown.” I urge you to attempt this for thirty seconds. My arms go tingly in under a minute.

King of the Mountain Pose

“Liz, you have trouble keeping your arms up, right?” she shouts to me in the farthest corner of the room, where I’ve sought refuge in an attempt to hide myself from the teacher-students and their circus-like contortions. My face flushes guiltily. I’ve been practicing yoga off and on for twenty years, and like to think I know a thing or two.

She calls me over to stand against a wall, where she places three blocks behind my upper, middle, and lower back, and one between my thighs. She has another student put a block behind my head while she lies on her back driving her feet into my hips. All thirty-odd students in the class are staring at me as Abbie points out my asymmetries and the fruitless angle at which I was attempting to hold up my arms without the scaffolding she has built around me. I feel a mustache of perspiration forming on my upper lip. “Straighten your arms,” she urges me. She’s narrating for the class now: “Her lungs are starting to fill, and she’ll be able to start breathing. That’s it, right! That’s where she belongs.”

After all the blocks and feet and straps have guided me into the position in which the pose is meant to be assumed, I find I can hold my arms up effortlessly for the entire nine minutes. I feel that elusive currency I’ve heard her mention coursing through my body, as though for the first time all the organs and muscles of my body are conspiring to help rather than hurt me. When I release my arms back to their sides and shake out my legs, I feel a new lightness, a flush of energy. I can see why people get addicted to this kind of yoga.

![]()

2

I sometimes think how odd it is that both a mastiff and a Chihuahua can be called “dogs.” The same holds true for Abbie Galvin’s bespoke Katonah style, whatever Vinyasa flow you’ve been doing at the gym, and yoga as practiced in India four and a half thousand years ago.

Yoga derives from the Sanskrit word yuj, meaning “to unite” or “to join,” in the way one would hitch an animal to a wagon (similar to yoke). The metaphor is about connection—the individual deriving power from a greater source outside oneself. The word comes from Sanskrit speakers of the Bronze Age who were migrating from modern-day Russia to the Indian subcontinent via the Indus Valley, circa 2500 BCE. Most of the yogic traditions of this era were transmitted orally—the highest teachings kept secret intentionally—and what was written down comes to us mostly through religious texts. The Rig Veda (circa 1500 BCE), a collection of hymns and one of the four canonical Hindu texts, depicts warriors practicing yoga prior to battle. The Bhagavad Gita, written sometime between 500 and 200 BCE, depicts a dialogue between the warrior Arjuna and his charioteer, Krishna, who reveals himself to be the Supreme Lord. Krishna lays out three paths of yoga through which the student can come to know his salvation. These include the path of action, or karma yoga; devotion, or bhakti yoga; and knowledge, jnana yoga. While the Bhagavad Gita mentions several modern-sounding yoga practices, such as breath control, this was intended for “withdrawal of the senses”—to receive strength from a higher power—rather than mind-body balance. Self-realization was the ultimate goal, with practice likely reserved for a rarefied group of holy men in the noble Brahmin caste.

The Yoga Sutras, 196 aphorisms on the theory and practice of yoga, was written circa 400 BCE and compiled by the author Patanjali. Little is known about his life, or if he is even a single individual. But his legacy is unparalleled. The Yoga Sutras are widely considered the ur-text of classical yoga, referred to as raja, or “royal” yoga, with philosophical roots not only in Hinduism, but also in Buddhism, Jainism, and other ascetic traditions of the Indian subcontinent of the era. The sutras lay out yoga as a system of living, the eight limbs (or elements) of this system being the yamas, moral imperatives such as nonviolence and truthfulness; niyama, virtuous habits and behaviors; asana, posture; pranayama, breath control; pratyahara, withdrawal of the senses; dharana, concentration; dhyana, contemplation; and finally samadhi, oneness. But while the word asana appears here as the third limb of yoga, it is defined not as the cycle of poses we think of today but merely as the position of the body that sets you up for seated meditation practice. The biggest difference between ancient and modern yoga is the emphasis on physicality. For thousands of years yoga was more synonymous with long sessions of stationary meditation than with exercise.

An important outgrowth of the Yoga Sutras was Tantra, which for the first time looked to the physical body as the route to enlightenment, aiming to awaken dormant energies. Tantra broke with the belief that there is a separation between the material and spiritual worlds; rather, the practitioner of Tantra can break down binaries such as pain and pleasure, or male and female, because all is contained in the universal consciousness. Everything is divine. This democratic worldview was reflected in the wide array of people who practiced Tantra: men as well as women, laypeople and nobles alike.

Hatha yoga evolved in part out of Tantra, with the teachings of hatha (meaning “sun” and “moon”) attempting to integrate the panoply of yoga systems that had sprung up across the subcontinent and urging the yogi to “traverse a path toward a goal.”3 The fifteenth-century Hatha Yoga Pradipika lays out a system of asanas that would be familiar to a yoga student today, including virasana (hero pose), gomukhasana (cow face pose), and savasana (corpse pose). Accompanying purification rituals were meant to ready the human body to commune with higher powers. Some of these practices are still familiar, such as neti, or cleansing of the nasal passages with water, which has become a recommended treatment for sinus problems, and mudras, gestures meant to balance the energetic channels of the body, which you might see your teacher demonstrate by placing thumb and forefinger together during seated meditation. Rituals you likely won’t see at your yoga studio include dhauti, which entails cleansing the stomach by swallowing a long piece of cloth, and basti, a yoga enema where one sucks water into the colon by creating an abdominal vacuum.

Hatha was practiced in India until the colonial era, when the postural shapes of lotus and backbending became associated with a British disdain for the “backwardness” of wandering yogis. As Mark Singleton writes in Yoga Body,4 his seminal history of physical yoga practice, “The emergence of the yogi as panhandling entertainer was a response to the uncompromising British clampdown on ascetic trade soldiers from the nineteenth century onward.” British colonists and Christian missionaries saw Hatha yoga as savage.

But as yoga was being dismissed by outsiders in India, it was becoming an object of fascination elsewhere in the world. In 1842, three Harvard alumni formed the American Oriental Society, which hoped to study a vastly defined swath of land they deemed “the Orient,” from Egypt to Japan. This “new” field of study was very much in vogue, and language and translation were essential to the endeavor.

The ability to disseminate Sanskrit texts in English made a big impact on the American Transcendentalist movement, which was then taking root in Harvard’s backyard. In 1843, Ralph Waldo Emerson read the firs...