![]()

Chapter 1

Facts About Life During The Civil War That Are Fiction Today

Religion was discussed by lots of people.

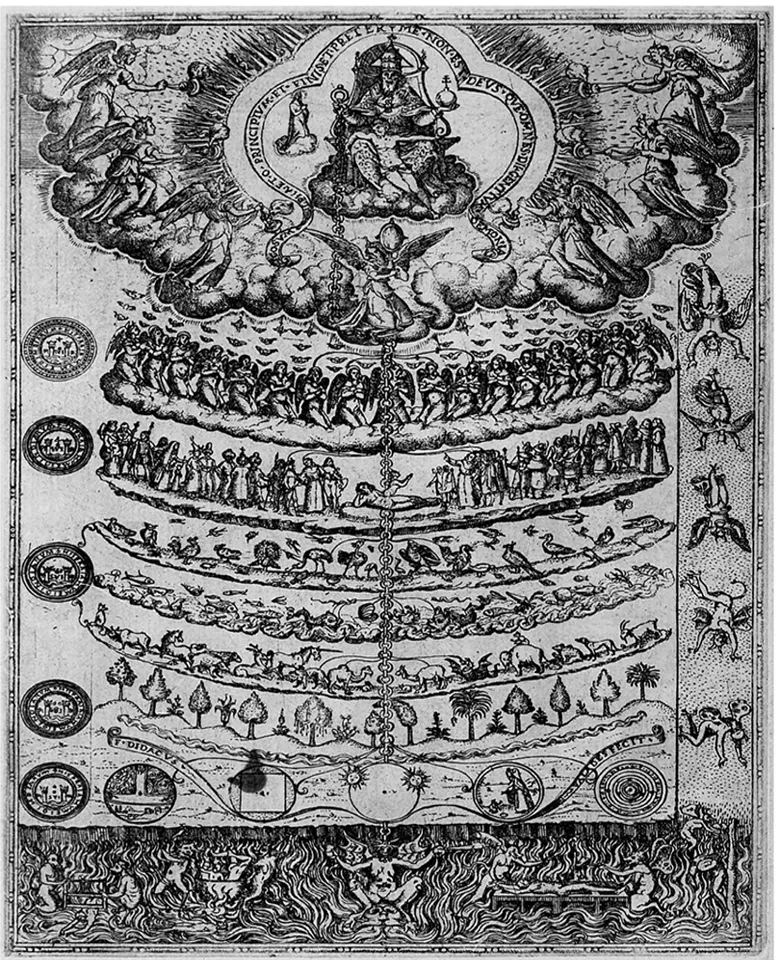

Nearly everyone was a religious believer during the civil war. It is not an idea that we find easy to understand today. This does not mean that people were nice all the time (far from it, as you will see in the book), or went to church every Sunday, or had religious thoughts every day. It does mean that nobody really doubted the basic truth of Christianity, the importance of the church, the existence of the soul, Heaven and Hell, in a system created by God. The social system on earth, with its powerful and powerless people, was a creation of God, a ‘chain of being’ that linked everybody together.

New ideas about religion were rare before the time of Henry VIII. After that, when people were having new ideas about religion, they were still talking about it, not rejecting it. People discussed religious questions far more than we do, and gave important meanings to things that people today might think are not worth worrying about. Take for, example, predestination – the belief that those going to Heaven, the elect or the ‘Saints’ – have been decided in advance by God and there is nothing that can be done about it on earth, and your good works and charity will make no difference. Some Protestants, mostly Puritans, believed in predestination and spent a lifetime hoping that they would be ‘in that number, when the saints go marching in’, to quote the song and apologies to Southampton Football Club – or the ‘Saints’, as they are still called.

The period before the civil war was full of religious disagreement. Should there be statues of the Virgin Mary in churches? Should altars Facts About Life During The Civil War That Are Fiction Today have rails around them? Should people turn their back to the altar? Where should the font be, at the entrance or in the church? Should people bow at the name of Jesus? Stained glass? Who should preach? Who should be in charge of the church, if anybody? Bishops, yes or no? This brings us to…

The Great Chain of Being. The Greatest Being is the King.

People cared about Bishops – enough to fight about them.

The least interesting word in this book is ‘Presbyterian’. I worry every time I use it that people will stop reading the book and do something more interesting. Presbyterian churches do not have bishops, and from a modern point of view that’s about it – what’s the fuss?

The existence of bishops and archbishops is not a subject that gets most people over-excited today. In the more religious sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, attitudes were different, stronger, and harder for people today to understand.

Some Protestants loathed bishops, because in the Catholic Church they were used to strengthen the power of the Pope. It suited British monarchs to have bishops despite the fact that many European Protestant churches had abolished them. It allowed British monarchs to control the nation’s religious life. Kings made the rules and bishops dealt out the punishment for breaking them.

English Protestants grumbled about bishops from Queen Elizabeth’s time. Many so-called ‘Puritans’ were disappointed that the new English protestant church had kept its bishops. Scottish Protestants also had bishops forced on them in 1584. When Elizabeth I died in 1603, this issue had not been settled.

Key Word – Episcopalian is the opposite of

Presbyterian and means a church run by bishops.

The other option was Presbyterianism, which had no bishops and local elders had control instead. This reduced the power of the monarch, but usually just increased the power of the local religious busybodies (so their enemies said). It did not mean than people could worship as they wanted; it just took the power away from the monarch. As James I said, rightly as it turned out – ‘No bishop, no king’. Bishops were abolished in England in 1646; three years later the king was beheaded. James got that right, perhaps more due to the stupidity of his son than his own powers of prediction.

The more radical alternatives were ‘Independent’ churches that were run, as the name suggests, by the local people on their own. They were free from both the king and the Presbyterian ‘morality police’. Some modern examples that had their roots in the civil war are Quakers and Baptists, both of which developed different ideas to the Church of England and still exist today enjoying the tolerance that they did not experience 300 years ago.

Independent churches were forbidden before 1640. Churches like those run by the female preacher Dorothy Hazzard in Bristol existed underground before the civil war but started to appear in public in the 1640s during the chaos caused by war. There is more about these groups in the book.

Bishops do not matter as much today, but in our story, please remember that bishops are a bit like Marmite; except that people don’t fight, maim and kill in arguments about yeast extract. Talking about fighting….

People didn’t really believe in ‘Live and Let Live’.

Today, in many parts of the world, there are societies where people of different religious beliefs or none can live together. The vast majority accept this, even though it does create problems now and then. This seems a reasonable position to us; religious faith is a matter of personal opinion and choice; people of different religions can work together as citizens of the same country; tolerating others is a good thing!

In the seventeenth century, this would have seemed wrong. It was more important to know the ‘truth’ than to be tolerant. The ideal situation was for a national church, with its entire people worshipping in exactly the same way. It was believed that a unified religous belief bound the people of a nation together. By saying the same prayers, going through the same church services and enjoying the same religious festivals, you become one nation.

It was also feared that a person who believed differently might not be loyal. In England, a Catholic could be accused of being loyal to the Pope, not the monarch. It was also feared that those with ‘wrong’ beliefs endangered their soul. So, it was a good thing to change people’s mind, to ‘proselytise’ (try to convert people, or brainwash them, depending on your view). It is not popular today, but 300 years ago, it was your duty. You were offering them hope in this world and salvation in the next. That is why some religious groups still knock on your door on a Sunday afternoon. They feel that it is their duty.

The idea of ‘live and let live’ did gain some ground in the war, although the conflict itself was not about religious toleration when it started in 1642. New groups like Baptists and Quakers pushed themselves forward and more or less dared people to stop them. Jews were allowed back into Britain for the first time during Cromwell’s Protectorate, but some people think this was done for an obnoxious reason – so they could be there for the end of the world and the ascent of Christians into Heaven and the Puritans could look on their disappointed faces as they either chose conversion to the truth or eternal damnation.

Throughout the whole of the seventeenth century, the negative attitude of Protestants towards Catholics is hard for most people today to understand, despite the fact that religious intolerance still bubbles under the surface in our so-called tolerant society.

Talking to God did not make you odd.

Lots of people today believe in the power of prayer, lighting a candle for the sick or other ways of asking for God’s help. In the seventeenth century, almost everybody believed God was active in the world and could choose to show his anger and appreciation. He could also help and hinder a person or a cause. For example, God had scattered the Spanish Armada with a gale (with the slightly unfortunate name of the ‘Protestant wind’) in 1588.

A good Christian would aim to do God’s work, and many Protestants believed that they had a personal relationship with Him. This was not in the form of a regular chat, but a kind of dialogue; they asked for a sign of God’s acceptance – his ‘favour’. ‘Godly’ people would try to behave in a way that He would approve; they would be regularly checking the health of their soul. Some godly people suffered through their life if they believed they had failed God’s tests; others would check everything that happened to them to search for evidence of God’s approval.

When Cromwell (allegedly) told his army in Ireland to ‘Trust in God and keep your powder dry’, he was telling them that because they were doing God’s work, they had to take the greatest care; but victory would have been His work no matter what they did. It was King Charles’s failure to win any wars that convinced Cromwell that God had withdrawn His support for the monarchy, and that Cromwell’s victories were a result of God’s blessing. Cromwell never gave himself any credit, which sounds modest, but he did see himself as an instrument of almighty God, which makes him seem a bit weird by today’s standards.

The strengths and dangers of this belief are obvious. Belief in God’s judgment could improve behaviour; but what if you decide that God’s work included punishing the Irish, like Cromwell did? Or Charles believing that starting a second civil war was what God wanted? Bad people used God to justify evil actions; we have seen this in our times. It was a tricky idea then, and it still is.

They were a long, long, long way from democracy in the seventeenth century.

Democracy as we know it – the vote for every adult, a government answerable to the people and a monarchy with limited power – was not what the civil war was about. When the war started, it was a row about how power should be shared out among the people who already had it. One side wanted a stronger monarch, and the other wanted a weaker one. Nobody went to war for votes for all men, let alone women.

Charles I and Jeffrey Hudson. Henrietta brought him up a Catholic – that’s Jeffrey, not the king. (Wellcome Collection)

It was a war about freedom. Freedom was not the same as democracy. It still isn’t. Equality is a different thing altogether; many people today believe that equality is a mad idea, which is what people thought about democracy in the seventeenth century. They thought the same in the eighteenth century too, much of the nineteenth and some of the twentieth. Oliver Cromwell and King Charles would both have agreed on this.

There were some democrats, but they were few and far between. They had a brief moment of influence. One group, the Levellers, are very popular today but they were a small group at the time. They are important today because they called for democracy in Britain, but they failed utterly in their aims and ambitions at the time. Cromwell had some of them shot, and nobody really minded very much at the time.

LITTLE KNOWN FACT – Henrietta Maria had

a constant companion, Jeffrey Hudson, an 18in

tall child, who was about 8 when given to her as

a gift. Hudson was a member of the court and

minor celebrity.

Even before the war started, it was a world of pain and heartache.

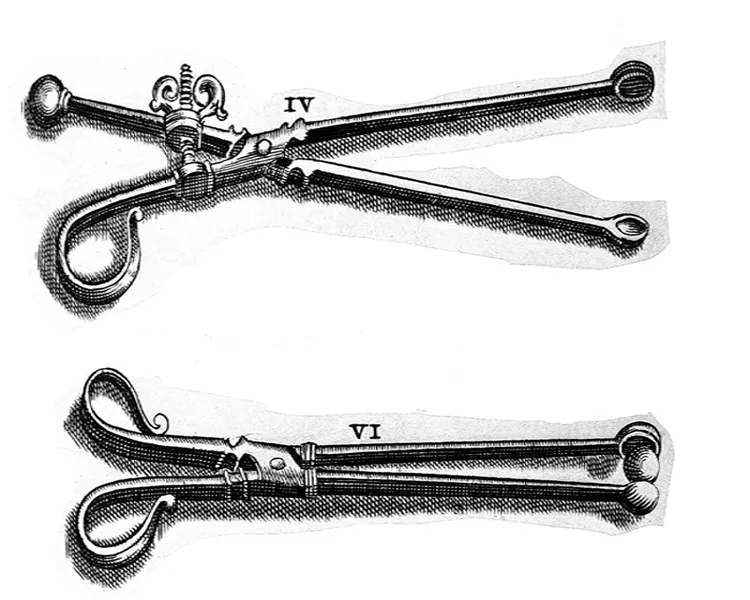

It is hard to know where to start. The pain-killing tablet did not exist; they could not dodge pain like we can. Dirty food and water made the stomach ache and puke more than we could ever imagine. Teeth were rotten, and skin and breath were bad. Medicine often helped with longstanding illnesses but was useless for injuries, plagues and emergencies. The cure for most epidemic diseases was death. Soldiers died after the battle because of the poor understanding of wounds – especially infections caused by dirty clothes being pushed into bodies by bullets and weapons. This was still happening in the First World War. Pregnancy and childbirth were a potential death sentence for mother and child. Many people were forced to make agonising decisions that would follow them through life. In May 1629, with his wife in labour, a breech birth was discovered and Charles had to choose between the life of his child or that of his wife.

Bullet extractor. Yes, it hurt.

Child mortality was the main reason why the average age of death was less than 30, even for the richest. It was normal to see your child die. There is no reason to believe that the people of the time got used to it, or that it affected them any less than it does now; for most people we have no evidence, but where we do, people were clearly devastated. In 1639, King Charles and his wife lost their new born child Catherine after a few hours; the couple, distraught and traumatised, collected mementoes of their baby like people would today. When Oliver Cromwell’s eldest son Robert died in the same year, he reported that ‘it was like a dagger to my heart’.

They knew what pain and loss was and they knew about war; many of the leaders of the civil war had fought bloody battles in Europe. When both sides chose war, they could not use ignorance as an excuse. They had seen Europe tearing itself apart over religion in the depressing but accurately named Thirty Years War, yet still they knowingly opted for war. That is how serious the issues were.

Permanent standing armies were unpopular.

You may have thought as much about armies as you have about bishops, but this was a big issue in the seventeenth century. Most people today are happy that Britain has a full time professional army, to be used for the protection of the country’s interests. We may disagree about the size and role of our armed forces, but virtually nobody wants them abolished.

This was not the case in the seventeenth century – there was no full time regular ...