![]()

CHAPTER 1:

SETTING THE SCENE

London at the time of Newman’s birth had expanded over the 1,750 years since its foundation by Roman settlers in AD 50.

It became the capital of England in the twelfth century and continued to grow in importance, due in large part to the presence of the royal court. By 1800, the city numbered more than a million inhabitants. The nineteenth century witnessed an unprecedented boom as the British empire expanded, and by 1900 London was the largest city in the world with a population in excess of six million inhabitants.

As it grew, London became a city of contrasts. No other writer captured the sense of the city and its colourful characters better than Charles Dickens. London had magnificent public buildings and institutions, and miserable slums and poorhouses. As the gentry built elegant residences and employed domestic servants, migrants, especially the impoverished Irish, filled the city to fuel the burgeoning economy.

The banks of the Thames, the artery of commerce, housed the docklands, rife with prostitutes and a warren for murderers. The stench of the East End was infamous and few, beyond its inhabitants, ventured into the maze of streets where refuse and excrement harboured typhoid, dysentery and cholera.

The Industrial Revolution in England developed production methods that had not changed for centuries. The spinning jenny transformed the woollen industry, while the steam engine heralded the locomotive. Coal, used to fuel factories and heat homes, turned the buildings black with carbon deposits and poisoned the citizens. Trains, trams and omnibuses pushed people out to settle in new suburbs, covering acres of green land and verdant forests with red and brown brick houses. While the rich strolled down the fashionable streets to visit their tailors or jewellers, the poor queued outside pawnbrokers, clutching their miserable possessions, which they lent the brokers until times improved. Often, rather than improving, they deteriorated, and the pubs and alehouses became the refuge of their wretched lives. When all hope died they were literally carted off to the workhouses or prison. Disease ensured that the last chapters of their lives were mercifully short, and every cemetery had a plot where paupers were thrown and covered with quicklime.

Nor was this phenomenon confined to London. Cities such as Manchester and Birmingham repeated the excesses of London. The rich accumulated wealth and occasionally salved their consciences by contributing to charities such as Thomas Coram’s Foundling Hospital, or the almshouses administered by several parishes.

Men were encouraged to join the army, at once relieving national unemployment while simultaneously expanding the empire upon which, in the words of the hymn, the sun never set. Queen Victoria, whose reign began in 1837, and her consort, Prince Albert, sought to strengthen ties between the royal houses of Europe through marital alliances. The country was ruled by the monarch and governed by parliament without a constitution. Socially, divorce was prohibited by law, abortion confined to the back streets and visible homosexual acts were criminal and punishable with hard labour or exile. The death penalty was administered by hanging, and executions took place in public.

Christianity, in its various forms, was the predominant religion of Britain. St Augustine was sent by Pope Gregory the Great to bring the faith to the Angles in the late sixth century and, over the centuries, Christianity gradually spread across the land. Catholicism, with its loyalty to the pope, was banished in the mid-sixteenth century when Henry VIII established himself as head of the Church of England in an effort to provide a legitimate heir to the Tudor throne. The last great split within the Anglican Church came when the Methodists broke away at the end of the eighteenth century.

Successive monarchs granted privileges to the Anglican Church, while new movements, such as Methodism and Liberal Christianity, gained popular support. The Salvation Army, founded in 1865 by the Methodist preacher William Booth, offered practical help with food and clothing, thus alleviating poverty to some degree. In 1829, Catholic Emancipation ended almost two centuries of penal laws, leading to a gradual although uneven improvement of the position of Catholics in society. But even their assimilation was slow. Jews, who worked largely in banking, the legal profession and the clothes trade, were the largest non-Christian group in England.

Despite the gloomy excesses of the century, London expanded in power and finance. Several museums and national art galleries opened or expanded. The British Museum was founded in 1753 and the National Gallery in 1824. Great Britain emerged from the Napoleonic Wars greatly enhanced, and throughout the nineteenth century the nation was the most economically prosperous in Europe, dubbed ‘the workshop of the world’. Despite the disparity of wealth, and the poverty of so many, Britain developed an almost impregnable belief in its superiority. The Victorian era was marked by strict social convention, and the Victorians themselves believed they were the most enlightened and civilised people to inhabit the British Isles.

John Henry Newman was born in London, at 80 Old Broad Street, on 21 February 1801. The house has long since been demolished, although a plaque commemorates the site. His parents, John Newman and Jemima Fourdrinier, had been married in 1799 at Lambeth in Surrey. Jemima, a descendant of prosperous French Huguenot papermakers and printers, was twenty-nine and her husband was thirty-four. John, whose immediate ancestors were from East Anglia and Holland, was a banker in the financial district of Lombard Street. His father was a grocer who had moved from Cambridgeshire to London. John founded a bank with his uncle and cousin, Richard and James Ramsbottom, which allowed him purchase a four-storey brick house in Southampton Street. It was a stone’s throw from Bloomsbury Park in a settled, respectable area. John Henry was baptised on 9 April that same year by the Reverend Robert Wells at the parish church of St Benet Fink.

In later years Newman recalled his parents with great affection. He had a tender love for his mother who was devout and read him stories from the Bible. His father was typical of his age, talking little about his religious beliefs but nonetheless assiduous in the practice of his Anglican faith. Newman remembered his paternal grandmother and his father’s sister with particular affection

The following year Jemima gave birth to a second son, Charles Robert. The first daughter, Harriet Elizabeth, was born in 1803, followed by a third son, Francis William, in June 1805. Jemima employed a nanny to assist her in caring for the four infants. A second daughter, Jemima Charlotte, was born in 1808, followed by Maria Sophia in 1809.

The middle-class family was able to provide early schooling at home with a governess, Mary Holmes, and in 1808, when Newman was seven, he was enrolled in Great Ealing School, which had been founded in 1698. Ealing was regarded as one of the finest schools and had a strong emphasis on sports, in which the boy had little interest. Louis Philippe, the future king of France, taught mathematics, a discipline in which Newman soon excelled. Directly across the road was the parish church of St Mary and the parish poorhouse.

Newman was a voracious reader, devouring exotic tales such as the Arabian Nights and the stories of Ulysses and Aeneas. While the boys played cricket, ‘fives’ tennis and other team games in the adjacent fields or swam in the school pool, Newman remained in the classrooms, neatly dressed in a waistcoat and trousers. His vivid imagination absorbed a vast amount of literature. One of the earliest surviving letters came from the then eight-year-old John Henry, written in beautiful copperplate to his mother.

Newman held the headmaster, Reverend Dr George Nicholas, then in his late thirties, in high regard. The school produced notable figures of the Victorian era, including the novelist William Thackeray, the biologist Thomas Huxley, the librettist William Schwenck Gilbert, the sculptor Richard Westmacott and Henry Rawlingson, a noted scholar of Assyrian cuneiform. Reverend Walter Mayers of Pembroke College, Oxford, was a regular visitor to the school and later John Henry was to attribute to him the means by which he came to a lively religious faith.

The school day was divided between lessons and physical exercise. Newman learned to dance, sing, fly kites and play cards and chess. He climbed trees and garnered a small group of like-minded friends who formed a secret society of which he was the leader. From time to time he won a book on prizegiving day. In addition to Latin, which he began to study at the age of nine (and Greek the following year), he added French, a language that was highly regarded at the time. At school he begin his studies in the viola, which was to be his companion until the last years of his life. He also had his first horse-riding lessons.

Newman boarded with some 290 other boys and, once a month, each child was able to go home on Saturday afternoon, returning on Sunday evening before supper. School holidays were valued by Newman chiefly because they afforded him time for uninterrupted reading. He recalled in latter life how he read the novels of Sir Walter Raleigh before it was time to get up and he also delighted in other novels, which he read throughout the day. He developed a precocious interest in religious literature. Writing in a brief autobiography five decades later, Newman recalled a French priest who taught English at school and a couple of Catholic families in the village. Apart from those isolated figures, the young man’s world was entirely Anglican.

At the age of fifteen, a little over a year before he left school, the teenager had a religious experience which had a profound and lasting effect on his personality. Years later Newman described it as a conversion that made him more aware of the presence and majesty of God. It was a gradual realisation that matured between August and December 1816, and it was during these months that he decided to lead a celibate life according, as he believed, to God’s will. He recounted this religious experience in his brief autobiography as being ‘more certain than that I have hands or feet’. The religious awakening came about through reading works by the sixteenth-century Swiss reformer, John Calvin, and his followers. The young Newman was deeply impressed with this Evangelical Protestantism. It concentrated on the personal salvation of each individual, which had been obtained by Jesus’ atonement with God the Father. Evangelical preachers underscored the grace by which each sinner had been saved by Jesus’ death. This resonated with a form of piety the young boy had learned from his mother. He also read Joseph Milner’s Church History and Newton’s The Prophecies, which introduced him to the Catholic religion and convinced him that the pope was the antichrist.

On 8 March 1816 Newman’s father’s bank had collapsed due to the effects of the Napoleonic Wars and he was unexpectedly faced with the task of paying creditors and searching for new employment. The family were forced to move to Alton in Hampshire, where John senior secured employment managing a brewery.

Having graduated from school in early 1816, Newman had to consider his future career. His first thought, and at his father’s prompting, was to enrol at Lincoln’s Inn to study law, but he decided instead to study humanities at Trinity College, Oxford. Newman successfully sat an entrance exam for Trinity College, where he commenced a degree in Classics and mathematics on 14 December 1816. The following year, on 8 June, he came into residence within the college and on 30 November he made his Holy Communion in the collegiate chapel. Among his fellow students was George Spencer, son of Earl John Spencer, who subsequently converted to Catholicism and became a celebrated member of the Passionist Congregation.

Given his father’s precarious financial situation and encouraged by his tutor Thomas Short, the young Newman sat for a scholarship on 18 May 1818. He was successful and was awarded tuition and sustenance fees.

![]()

CHAPTER 2:

OXFORD

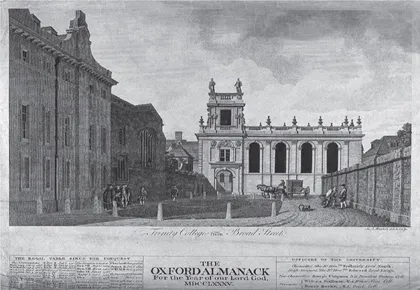

Line engraving of Trinity College, Oxford, from Broad Street.

The twin universities of Oxford and Cambridge were the premier seats of learning in Victorian England. Monks studied at Oxford as early as 1096 and the university expanded in 1167 when Henry II banned English students from studying at the University of Paris. After a row between Oxford students and townsfolk in 1209, several students and tutors moved east to Cambridge where they founded a new college. With the break with Rome under King Henry VIII, both universities became Anglican and remained so until 1856.

Trinity College, Oxford, dated from 1555, when Thomas Pope bought Durham House where the monks of Durham Abbey and cathedral had studied since 1291. The house had been appropriated by Henry VIII in 1545. The elegant sandstone building was small, and there were no more than a few score undergraduates, who attended a number of tutorials each week.

Newman was impressed by the work of a former fellow of Trinity, Thomas Newton, who later became Bishop of Bristol and Dean of St Paul’s in London, and by the Cambridgeeducated clergyman, Joseph Milner, and his brother Isaac, who wrote the History of the Church of Christ. Of all the works Newman read in his early years at Trinity, A Commentary on the Whole Bible, by Reverend Thomas Scott, made the deepest impression. Newman tried unsuccessfully to meet Scott, who was also one of the founders of the Church Missionary Society.

Oxford tuition consisted of reading widely according to texts prescribed by the tutor and discussing them in private sessions. Books were expensive and a large selection, many of them centuries old, was kept in the oak-panelled library. Books could be requested from the librarian who curated the volumes. Medieval manuscripts were still commonly available in college libraries in Newman’s day. During term time, he studied for ten hours a day, and up to fourteen close to exams.

Students, usually no more than half a dozen, gathered in the rooms of their tutors weekly. The tutor discussed the reading material that had been set the previous week and answered questions. The students boarded in the college, attended Matins and Evensong in the college chapel and dined in Hall. Discipline was strict and undergraduates were expected to honour their college. Drunkenness or other forms of poor behaviour were admonished and punished.

The first written glimpse of John Newman’s propensity for friendship occurred in November 1818 when, along with his new friend J.W. Bowden, he composed two cantos, entitled St Bartholomew’s Eve. Newman showed delight at finding a friend who shared his passion for the romantic medieval world.

Newman also read the more secular works of the historian Edward Gibbon, whose Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire fascinated him, and the works of the Enlightenment philosopher David Hume. He diligently attended his tutorials with Dr Thomas Short, submitted written essays and was confident of achieving a good grade in his final examination. At his father’s insistence, he put his name down for Lincoln’s Inn in 1819, with the intention of studying law.

Shortly after his final examination for a Bachelor of Arts taken on 5 December 1820, the results were posted on the board opposite the porter’s lodge inside the main arched entrance. Newman had been called for the examination a day before he expected. To his shock and bitter disappointment, he did poorly, achieving only a third-class BA degree. He smarted under the humiliation, but years later he claimed that his father’s financial situation had prevented his studying for an honours degree.

On 1 November 1821 his father was declared bankrupt. Everything in the house was sold. When he was in extreme old age, a Mrs Fox wrote to Newman saying that she had come across old viola scores inscribed with his name.

While he hoped to remain at Oxford, there was little chance that he could find a position at Trinity College. He now had to make the difficult choice between applying to another college for a fellowship or returning to London in the hope of finding employment.

Becoming a fellow at an Oxford college required that one remain celibate and unmarried. It was a throwback to the era when monks were lecturers and taught their novices. Those who accepted fellowships knew the sacrifices that would be required for the needs of the college. Teaching was not a wellpaid profession and fellows often became clergymen in order to have ‘a living’, or parish, which would supplement their income and provide a residence in later life. On 11 January 1820, John Henry had decided to take Holy Orders in the Church of England. Some weeks later, he applied to Oriel College in the hope of receiving a fellowship and thus becoming a member of the academic staff, for which lodgings were provided.

Oriel, Oxford’s oldest college with a royal charter, had been founded under Edward II in 1326. The holdings of the library dated to the mid-twelfth century and the college had been largely rebuilt in the mid-seventeenth century. Although a small college, it was elegant and had a good reputation for theology, medicine and law, and boasted eminent graduates such as Henry VIII’S chancellor, Sir Thomas More, adventurer and writer Sir Walter Raleigh and many members of the British aristocracy. The college’s reputation had taken a downturn in the early eighteenth century, but between 1780 and 1830, the provost and fellows improved academic standards by extending the library and raisin...