![]()

Dental diseases have been a part of human existence since the days of earliest man. Paleolithic human remains contain evidence of advanced dental attrition and periodontal disease.1 Ancient Egyptian skulls contain evidence of dental caries and bone destruction from periodontal infection.1 Toothache is among the common ailments described in the earliest known textbooks of medicine. How did man cope with the excruciating pain of toothache and how did he accommodate to the loss of teeth? How did the practice of dentistry develop and flourish as a separate profession from medicine? To answer these questions and uncover the origins of dentistry, we must examine the records of ancient civilizations.

Ancient Egypt

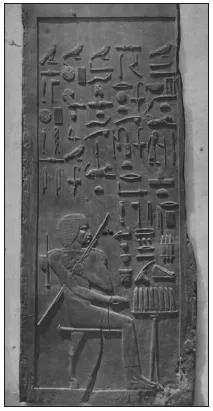

The Egyptians created numerous tomb inscriptions and papyri that have allowed us to form a vision of their way of life, including their approach to maintaining health and dealing with disease. The healing arts were closely integrated with their religious beliefs, and practitioners of medicine were members of the priesthood. Tomb inscriptions and early histories have suggested that Egyptian medicine may have been diversified. Herodotus, the Greek historian who traveled through Egypt, described the country as rich with practitioners, some specializing in diseases of the eyes, some for the heart, some for the gut, and some for the teeth.2 Egyptian tomb inscriptions have revealed that approximately 150 individuals practiced medicine; at least three of them, and perhaps as many as nine, appeared to have treated dental problems.3,4 The earliest dentist, Hesyre, is depicted on carved wooden panels recovered from excavations at Saqqara near Cairo (Fig 1-1). The panel inscription shows that he held the titles of both physician and dentist.4

Fig 1-1 Wooden panel recovered from an Egyptian burial chamber depicting Hesyre and identifying him as a physician and a dentist.

Egyptian medical practice was dominated by the use of herbal remedies concocted in the form of emetics, diuretics, purgatives, and palliative dressings.5 The Egyptian pharmacopeia consisted of mineral, plant, and animal products, often in the form of powders or salves. Egyptian surgeons were adept in the use of the knife and cautery for excision or ablation of diseased tissues.

Examinations of the skeletal remains recovered from Egyptian burial sites have shown that 10% of teeth had dental decay, and 20% contained evidence of periodontal disease. Dental calculus (tartar) was present on 50% of all teeth.6 Radiographs of two royal mummies, Amenhotep III and Ramesses II, revealed extreme tooth abrasion, periodontal disease, and periapical abscesses but no evidence of dental treatment.4 From thousands of Egyptian mummies that have been examined, there is no evidence that Egyptians performed any dental operations. Although instruments that may have been used in medical practice have been recovered in burial chambers, none appear to have been specifically designed for use in dental procedures.4

In his studies of Egyptian skulls, F. F. Leek concluded that excessive attrition of occlusal surfaces was the greatest cause of death of the dental pulp, leading to abscess formation, osteomyelitis, and the spread of infection into the jaws.1 Erosion of enamel and dentin was caused by the consumption of coarse bread and fibrous vegetables.7 The masticating (grinding) surfaces of the first molars exhibited the most severe wear, with the crowns often eroded to the gum line.

Tooth erosion and dental abscesses affected all classes, including members of the royalty.8 Loss of alveolar bone from periodontal disease is a common finding in ancient Egyptian skulls. The cause of the bone loss appears to have been an excessive accumulation of tartar on the roots of the teeth. No toothbrushes or instruments for scraping tartar have ever been found among Egyptian artifacts. Although dental decay was relatively rare in ancient Egypt, it became more prevalent at the time of the construction of the Great Pyramids. Excavation of 500 skeletons of aristocratic families at gravesites of the Giza pyramids revealed that the prevalence of tartar, caries, and dental abscesses were equal to that found among modern Egyptian populations. This decline in dental health may have been the result of changes in the quantity or form of carbohydrate intake. In 1920, paleoanthropologist Sir Armand Ruffer concluded, “Carious human teeth from ancient remains have been discovered in so many places that it is legitimate to doubt whether there was ever an epoch when the human species was not cursed by toothache.”7

From the archaeologic record, it appears that Egyptians did not practice operative dentistry.1 No tooth filled with gold or any other metal has ever been found within Egyptian tombs. Evidence suggests that severely infected and loose teeth were not extracted.8 It would seem that a suffering dental patient had nothing but herbal remedies and magical incantations to afford relief from the pain of toothache and infection.

Among the papyri that have been recovered from Egyptian gravesites, the Ebers Papyrus and the Edwin Smith Papyrus are special sources of medical information. The ability to decipher the hieroglyphic script of the papyri and tomb inscriptions was made possible by the discovery of the Rosetta Stone during Napoleon’s illfated expedition to Egypt in 1799. The stone fragment found in the village of Rosetta in the Nile Valley was inscribed with a message written in the three writing systems used in Egypt: the hieroglyphic (or picture form), the hieratic (religious form), and the demotic (used in everyday communication). In 1822, Jean-Francois Champollion, a master of Greek and eastern languages, translated the demotic text into French and thereby was able to decipher the hieroglyphic sign text. Some hieroglyphics suggest that there may have been physicians for the teeth, as depicted by the juxtaposed symbols of an eye (for he who cares for) and a tusk (for teeth). Similarly, the juxtaposition of a bird (signifying the greatest), a tusk (teeth), and an arrow (a medical practitioner) was translated to mean the “greatest of those who deal with teeth” (upper right corner of Fig 1-1). However, not all experts of Egyptian hieroglyphics are in complete agreement on these interpretations.1

The Ebers Papyrus, dating from around 1500 BC, is significant because of its description of the heart and its blood supply, evidence of the relatively advanced knowledge of the vascular system as well as the major organs of the human body, believed to have been gained in the practice of embalming and mummification. Dental diseases such as gumboils, pulpitis, and alveolar abscesses are described in the Ebers Papyrus and confirmed by the pathologic findings of the skeletal remains.9 Recipes for powders and ointments for tooth and mouth ailments are contained among the 700 formulas listed in the Ebers Papyrus.1

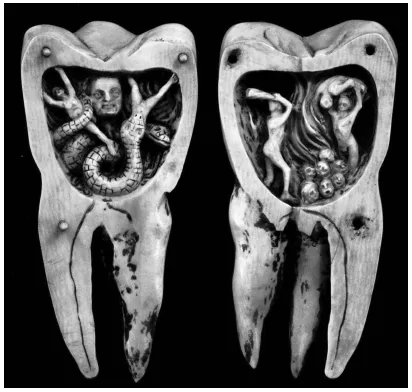

The Papyrus Anastasi is of interest to dental science in that it contains the idea that toothache was caused by worms that had burrowed into the tooth’s interior (Fig 1-2). The earliest version of this myth can be traced to a Mesopotamian clay tablet, dating back to 1800 BC, discovered in the ancient city of Sumer (now Nippur), Iraq.2 The myth of the tooth worm continued to be popular well into the late Middle Ages and was accompanied by the prescription that toothache could be treated by fumigating the infected tooth with the fumes from burning henbane seeds.

Fig 1-2 Ivory carving depicting worms and demons as the cause of toothache.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus, an even older text dating back to 2700 BC, contains 48 medical case histories of Egyptian medical practices for dealing with various injuries, including a description for reducing fractures of the mandible.2 The level of anatomical and physiologic knowledge contained in the Edwin Smith Papyrus is superior to other known papyri. Its emphasis on surgical technique suggests less reliance on the healing power of magic and religious incantation. However, with the exception of the mandibular fracture description, there are no other references to oral diseases in the Edwin Smith Papyrus.1

Based on research and critical examination of the literature, Thomas Nickol concluded that there was no evidence of any prosthetic work being carried out on the dentition or of any surgical treatment of teeth by medical practitioners in ancient Egypt.10 The only treatment of dental disease and mouth ailments was by herbal preparations applied to the problematic sites by either physicians or, more likely, artisans of a lower, nonpriestly class. According to Guerini, there is no proof that any fillings or artificial teeth were ever found in mummies.11 In the thousands of Egyptian skulls excavated at burial sites, there are only two examples of attempts to secure loose teeth with gold wire. These were recovered from a burial chamber at Giza in 1914.2

Guerini wondered why the Egyptians, talented in the craftsmanship of gold and other plastic arts and fond of beautifying the human body, did not undertake dental restorative work.11 The artisans who fabricated the exquisite burial masks and other ornamental objects recovered from the pyramids had the necessary talent...