![]()

The physical world is a cunning, deceitful character, full of lies, or worse, half-truths. It is not to be trusted at any time, nor at any cost. The brain is a flawed detective with a loaded die for a compass, working on lousy pay with fuzzy data, and a strict, sometimes literal, deadline. But over eons of evolutionary time, the brain has always had one crucial advantage: it knows that the physical world has to play by certain rules, rules that are ultimately derived from the laws of physics. Armed with this singular insight, the brain tests and retests, millisecond by millisecond, multiple competing hypotheses about what in the world might have produced the evidence of its own eyes, ruthlessly casting aside red herrings and fallguys one by one, by one, until there is only a single suspect who does not have a rock-solid alibi: and that is the one chosen by the brain, that is what we see.

— Stone (Vision and Brain, 2012)

Much like the physical world, cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) has to play by certain rules, rules that are ultimately derived from the laws of physics. It is a beautiful instrument but can be cunning, deceitful, and full of lies (or worse, half-truths). When can we trust it? How much can we trust it? And at what cost?

Why We Wrote This Book

The purpose of this book is twofold. First, we wish to address cone beam imaging in endodontics from both technical and theoretical perspectives. We will examine how it differs from periapical (PA) projection radiography by developing a more sophisticated understanding of how the image is acquired, processed, and reconstructed prior to it being viewed and interpreted. Each of these phases in cone beam technology has its own important parameters that could fill an entire chapter. Therefore, the chapters in this book will provide the practicing clinician a background for understanding how CBCT volumes are reconstructed from the projection data that are typically observed as the examination is performed.

Second, we will introduce vital perceptual and cognitive issues related to image interpretation and important considerations in the related academic field of perception metrology (how perception is measured). These issues affect diagnosis, treatment planning, decision-making, and how treatment outcomes are assessed. The chapters on these topics are heavily referenced for the reader interested in further study of this important area.

The overall goal of this book is to introduce the potential and capabilities of modern CBCT imaging and compare and contrast them with traditional PA radiography. The authors strongly believe that a fuller understanding of how a CBCT image is acquired, processed, reconstructed, viewed, and interpreted will result in a more sophisticated and skilled use of this tool, thereby avoiding many common errors that have frequently resulted in overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Issues with Existing Work

Unfortunately, expertise on the interpretation of traditional PA and panoramic radiography does not transfer well to CBCT interpretation, which requires an understanding of the physics of the image generation process and the underlying nonlinear mathematical process for reconstructing the imaged section. While we all took physics and calculus as prerequisites for dental school, that knowledge has likely been lost in the intervening years or decades. In his preface to Intermediate Physics for Medicine and Biology (Springer, 2007), Russell K. Hobbie acknowledges similar discrepancies in medical students:

Between 1971 and 1973 I audited all the courses medical students take in their first two years at the University of Minnesota. I was amazed at the amount of physics I found in these courses and how little of it is discussed in the general physics course.

I found a great discrepancy between the physics in some papers in the biological research literature and what I knew to be the level of understanding of most biology majors or premed students who have taken a year of physics. It was clear that an intermediate-level physics course would help these students. It would provide the physics they need and would relate it directly to the biological problems where it is useful.

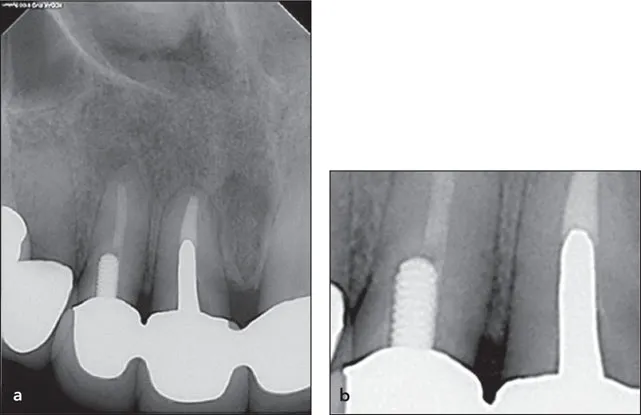

Therefore, the authors will make every effort to tie some of this more difficult material to clinically relevant problems, using the absolute minimum amount of mathematics. One only needs to reflect back to the introduction of digital PA radiography and the widespread interpretive errors made in the viewing of those radiographs to appreciate how a new modality in imaging can have detrimental clinical ramifications and consequences not anticipated at its introduction. Consider the image-processing effects that resulted in findings of “recurrent decay” or “open margins” and the ensuing overdiagnosis (incorrect diagnosis) and unnecessary treatment that resulted. Figure 1-1 clearly shows a digital image-processing ringing artifact at the sharp edges of the porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns, potentially leading to a misinterpretation of open margins. However, the clinical examination of the marginal integrity with the microscope revealed no such findings.

Fig 1-1 (a) A ringing artifact is present at the sharp edges of the porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns, potentially leading to a misinterpretation of open margins. (b) Closer inspection reveals a matching white trace following the crown margins and the outline of the cast post in the central incisor. (Courtesy of Dr Jeffrey B. Pafford, Decatur, Georgia.)

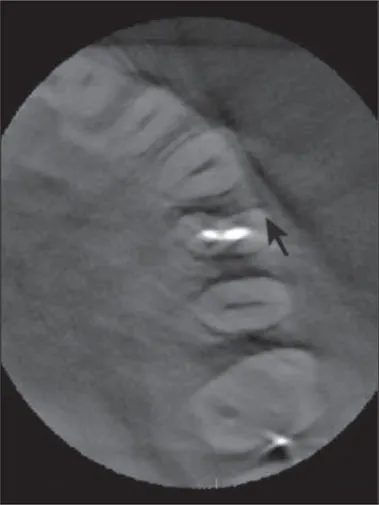

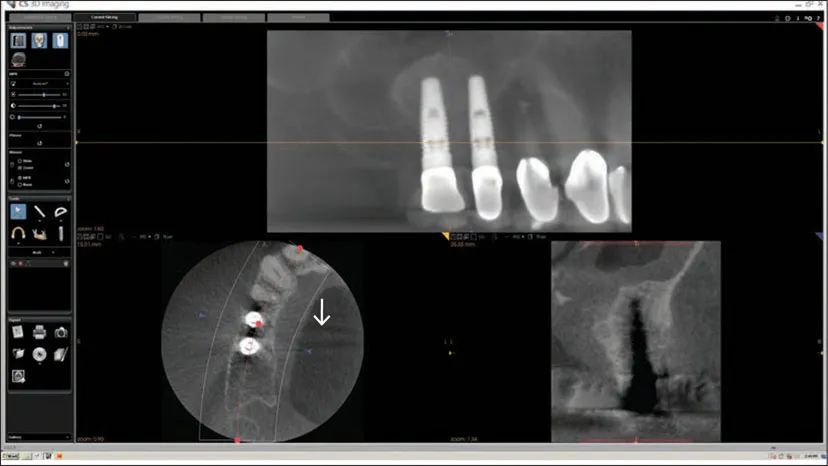

The cases and reconstructions in Figs 1-2 to Figs 1-9 show a variety of findings that appear to mimic actual pathology such as cracks and fractures, decay, and bone loss as well as unusual root forms—essentially every finding that we identify with PA radiography. Which of these findings are real? Which are full of lies? Which are worse—half-truths?

Fig 1-2 The arrow is as it appears in a textbook on endodontic radiology, and it is said to “point to the crack on the buccal aspect of the maxillary first premolar.” While there appears to be a radiolucent line where the arrow points that mimics our mental model of what a crack might look like in imaging, is that actually evidence of a crack? How confident should we be as to the presence of a crack based on that finding? Is there not a nearly identical finding on the untreated canine? What else could explain these findings? What other artifacts appear present in this reconstructed section? (Reprinted with permission from Basrani B. Endodontic Radiology, ed 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.)

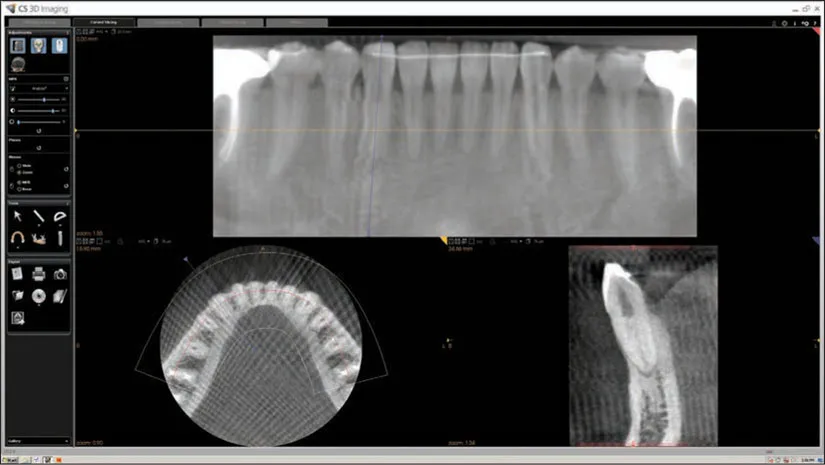

Fig 1-3 Here in the pseudo-PA reconstruction, the bone between the implants appears fairly normal, but in the axial and transsagittal slices, there appears to be marked bone loss between the implants. How do we understand and reconcile these seemingly disparate findings? In the axial slice, there are also converging dark/light streaks (white arrow) from the two implants appearing to go across the palate toward the contralateral side. What is the cause of that finding? What does that finding suggest?

Fig 1-4 Here in the pseudo-PA reconstruction, the second premolar and molars appear “double,” but the incisors, canines, and first premolar appear fairly normal. There are many streaks in the axial slice. The canal spaces are not very visible, and the image appears grainy. What are the causes of these imaging findings?

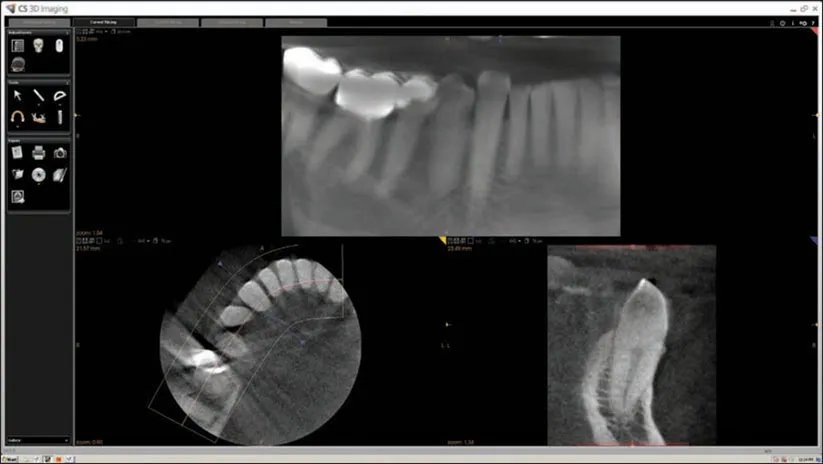

Fig 1-5 On this pseudo-PA reconstruction, why do the roots of the mandibular incisors look so different in mesiodistal width? In the transsagittal slice, is the premolar decayed?

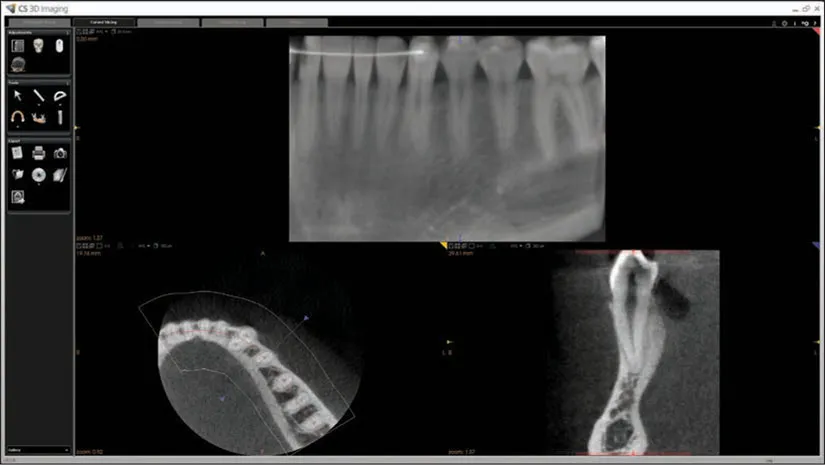

Fig 1-6 In this case presented in a paper, how confident should we be of the claimed perforation? Are there any other hypotheses that might explain the radiographic findings? (Reprinted with permission from Scarfe WC, Levin MD, Gane D, Farman AG. Use of cone beam computed tomography in endodontics. Int J Dent 2009;2009:634567.)

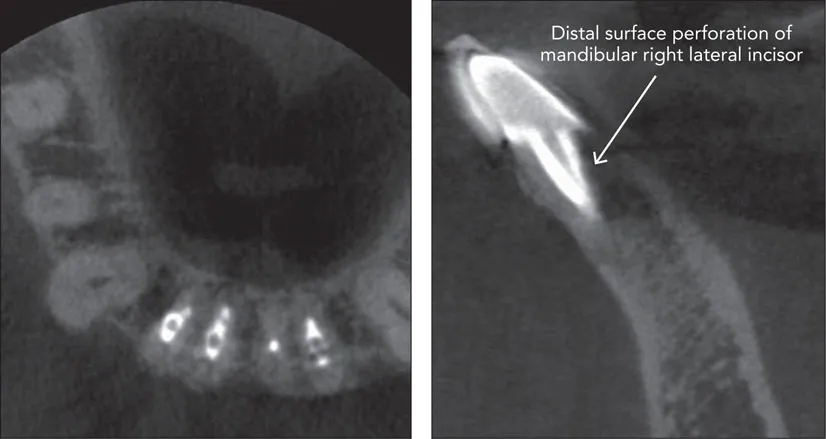

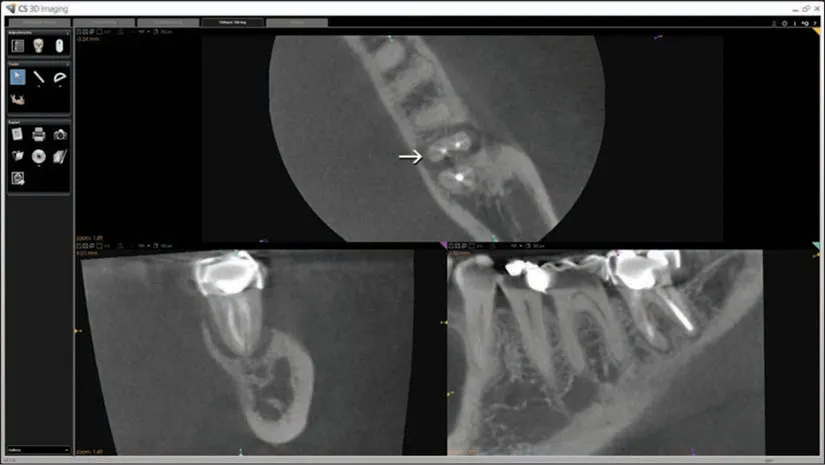

Fig 1-7 (a and b) Does the axial slice (arrow) show an ectopically placed canal? Is there a lateral canal feeding the lateral root “lesion”? Is that a large “lesion” in the furcation of the first molar? Is there sinusitis? Do the sagittal (arrows) and coronal slices have evidence of resorption? Why do these images look so grainy and low in contrast?

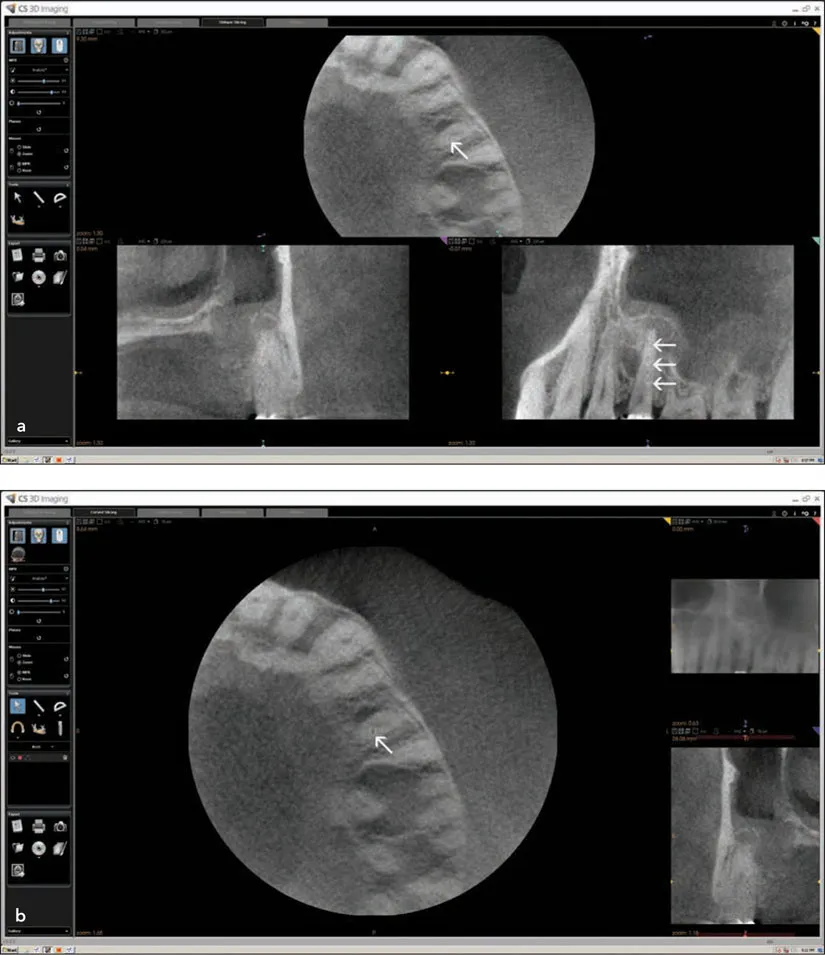

Fig 1-8 In the axial slice, there appears to be a vertical root fracture or crack on the lingual aspect of the mesial root (arrow) similar to the finding presented in Fig 1-2, and the distal root appears cracked in a mesiodistal direction. Is the “lesion” in the furcation bone between the mesial and distal roots bone loss related to the crack?

Fig 1-9 What is causing the crosshatching pattern across the entire axial slice? In the pseudo-panoramic image, the canine has a very odd appearance, yet it appears fairly normal in the transsagittal slice.

Even the most experienced and competent clinicians make these interpretive mistakes because the eyes see only what the mind has language to describe. Over 50 years ago, well before CT scans, Tuddenham provided some insight into the difference between seeing what we know and knowing what we see:

Meaning is ascribed to this incomplete representation of the retinal stimulus pattern by matching it with our memories of previous visual experiences, and perception is thought to occur when the transmitted pattern is identified with and completed from one of those traces of memory. There can be no perception, therefore, without some degree of recognition.

What if there are no previous visual experiences to be had? Without an understanding of the differences in the digital image generation processes and associated potential artifactual findings, and without appropriate language to describe those findings, one is left with description and characterization based on what one understands about film. As these examples show, we are seeing descriptions and characterizations with CBCT that rest upon the previous visual experiences from PA projection radiography. This book is an attempt to provide the clinician with an improved and more sophisticated understanding of CBCT imaging technology that will hopefully lead to improved clinical performance and patient outcomes.

Why It Matters

In their two-part review article, Miracle and Mukherji bring issue to the increasing use of a point-of-service model of dentomaxillofacial imaging with CBCT, citing concerns with appropriateness, outcomes, and lack of training and expertise by the prescribing and interpreting clinician:

Both in medical and oral and maxillofacial imaging in dentistry, CBCT has been largely adopted as an office-based service.

As with any emerging imaging technology, use of CBCT scanners has been the subject of criticism as well as acclaim. The technology itself is limited by lack of user experience and what is currently a relatively small body of related literature. The point-of-service operational model that dominates diagnostic head and neck CBCT imaging practices has also drawn criticism.

The advent of CBCT technologies has also fueled the controversy surrounding office-based imaging, which is usually performed and interpreted by nonradiologists often without the accreditation, training, or licensure afforded by the radiology community.

Dentists have traditionally been able to fly under the radar when it comes to interpreting imaging and planning treatment based on that interpretation. We have not been held to the same standard of care as medical radiologists or trained to the same level. We should consider this issue very carefully as a specialty. For these and other reasons, we feel that the subject, although difficult and technical, is important and should constitute the very first step in any clinician’s education in learning how to use this wonderful new instrument. Endodontics can be practiced at a high level without CBCT imagi...