![]()

1.

Towards a Treaty

FROM THE TIME OF THEIR FIRST FLEETING ENCOUNTER WITH EUROPEANS in the seventeenth century through to the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and formal British annexation in 1840, Māori communities underwent enormous changes. Along the way they had seen growing numbers of Europeans settle in their country, the independence of which had been formally recognised by the British government just a few years before it determined to negotiate for the transfer of sovereignty over New Zealand to itself.

1.1 Early Māori and Pākehā encounters

The first known encounter between Europeans and Māori occurred in December 1642, when Dutch explorer Abel Tasman anchored in Golden Bay. Cross-cultural misunderstandings resulted in the killing of four of his crew, with an unknown number of local Māori killed in retaliation. It was a further 127 years before the next Europeans ventured towards the New Zealand coastline. James Cook made three voyages between 1769 and 1777. He was followed by French explorers Jean François Marie de Surville in 1769 and Marion du Fresne in 1772. Further bloodshed resulted, but mutual curiosity and exchange, trade, sexual relations with local women, and other forms of hospitality also marked these later encounters. Contact with the outside world, whether for better or worse, thereafter became a regular feature of the Māori experience, especially for coastal tribes.

1. First encounter with Abel Tasman begins with a wary standoff

Abel Tasman, Journal, 19 December 1642, in Robert McNab (ed.), Historical Records of New Zealand, 2 vols, Government Printer, Wellington, 1914, vol. 2, pp. 21–22.

Early in the morning a boat manned with thirteen Natives approached our ships; they called out several times, but we did not understand them, their speech not bearing any resemblance to the vocabulary given us by the Hon. Governor-General and Councillors of India, which is hardly to be wondered at, seeing that it contains the language of the Salomonis Islands [Solomon Islands], &c. As far as we could observe, these people were of ordinary height; they had rough voices and strong bones, the colour of their skin being between brown and yellow; they wore tufts of black hair right upon the top of their heads, tied fast in the manner of the Japanese at the back of their heads, but somewhat longer and thicker, and surmounted by a large, thick white feather. Their boats consisted of two long narrow prows side by side, over which a number of planks or other seats were placed in such a way that those above can look through the water underneath the vessel; their paddles are upward of a fathom in length, narrow and pointed at the end; with these vessels they could make considerable speed. For clothing, as it seemed to us, some of them wore mats, others cotton stuffs; almost all of them were naked from the shoulders to the waist. We repeatedly made signs for them to come on board us, showing them white line and some knives that formed part of our cargo. They did not come nearer, however, but at last paddled back to shore.

2. James Cook’s observations on Māori society

James Cook to John Walker, 13 September 1771, in Robert McNab (ed.), Historical Records of New Zealand, 2 vols, Government Printer, Wellington, 1914, vol. 2, pp. 79–80.

The inhabitants of the country are a strong, well-made, active people, rather above the common size. They are of very dark brown colour, with long black hair. They are also a brave, warlike people, with sentiments void of treachery. Their arms are spears, clubs, halberts, battleaxes, darts, and stones. They live in strongholds of fortified towns, built in well chosen situations, and according to art. We had frequent skirmishes with them, always where we were not known, but firearms gave us the superiority. At first some of them were killed, but we at last learned how to manage them without taking away their lives; and when once peace was settled, they ever after were our good friends. These people speak the same language as the people in the South Sea Islands we had before visited, though distant from them many hundred leagues, and of whom they have not the least knowledge or of any other people whatever. Their chief food is fish and fern roots; they have, too, in places, large plantations of potatoes [kumara], such as we have in the West Indies, and likewise yams, etc. Land animals they have none, either wild or tame, except dogs, which they breed for food. This country produceth a grass plant like flags, of the nature of hemp or flax, but superior in quality to either. Of this the natives make clothing, lines, nets, etc. The men very often go naked, with only a narrow belt about their waists; the women, on the contrary, never appear naked. Their government, religion, notions of the creation of the world, mankind, &c., are much the same as those of the natives of the South Sea Islands.

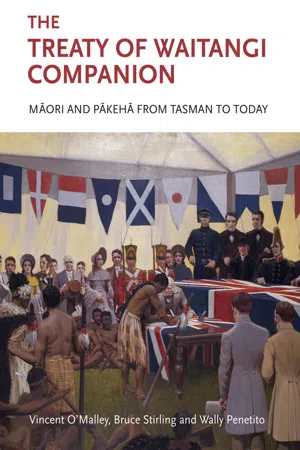

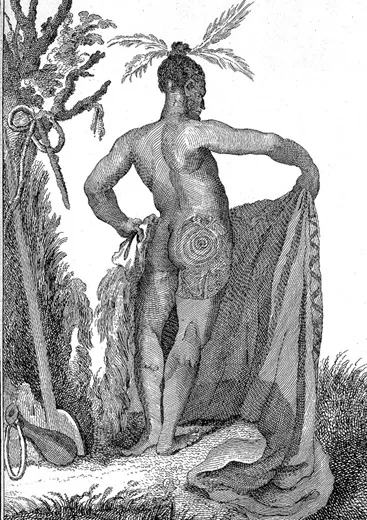

Figure 1. Despite the bloody outcome, Marion du Fresne and many of his crew were inclined to idealise Māori as ‘Noble Savages’, as seen in this portrait from an unknown artist on the 1772 voyage to New Zealand of Northland chief Te Kauri. artist unknown, ‘tacouri’, [1783], publ-0150-002, atl

3. Cook’s visit to Whitianga recalled by a chief many decades later

John White, Ancient History of the Maori, His Mythology and Traditions: Tai-nui, 6 vols, Government Printer, Wellington, 1888, vol. 5, pp. 128–29.

We were at Whitianga when a European vessel came there for the first time. I was a very little boy in those days. The vessel came to Pu-rangi (distant) and there anchored, soon after which she lowered three boats into the sea, which pulled all over the Whitianga Harbour. We saw the Europeans who pulled in those boats, and said that those Europeans had eyes in the back of their heads, as they pulled with their backs to the land to which they were going. These Europeans bought our Maori articles, and every day our canoes paddled to that ship, and what we bought from those Europeans was nails, flat iron (hoop), and axes. [… .]

When that first ship came to Whitianga I was afraid of the goblins in her, and would not go near the ship till some of our warriors had been on board. It was long before I was reconciled to those goblins or lost my fear of them. At last I went on board of that ship with some of my boy-companions, where the supreme leader of that ship talked to us boys, and patted our heads with his hand. He was not a man who said much, but was rather silent; but he had a grand mien, and his appearance was noble, and hence we children liked him, and he gave a nail to me.

4. Marion du Fresne’s breach of tapu results in his killing

Augustus Earle, A Narrative of a Nine Months’ Residence in New Zealand, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman, London, 1832, p. 122.

Marion’s entire ignorance of the customs of the New Zealanders occasioned that distressing event: as … strangers, not acquainted with their religious prejudices, are likely to commit some fatal error; and no action is more likely to lead a party into danger than an incautious use of the seine, for most of the beaches … are taboo’d. This led to the dreadful fate of Marion and his party. I understood from George, that when Marion’s men assembled to trail their net on the sacred beach, the natives used every kind of entreaty and remonstrance to induce them to forbear, but either from ignorance or obstinacy, they persisted in their intentions, and drew their net to the land.

5. His death is revenged many times over

Jean Roux, Journal, June 1772, in Robert McNab (ed.), Historical Records of New Zealand, 2 vols, Government Printer, Wellington, 1914, vol. 2, p. 433.

I am perfectly convinced that these people had no acquaintance with Europeans, and that they were consequently in complete ignorance of the effect and carriage of our firearms, seeing that they imagined they could ward off the bullets by the cloaks they wore … I estimate that about four hundred and fifty men had remained to defend the fortress. Of this number, only two large canoesful got away, the rest had either been killed or had been drowned, for they threw themselves into the sea to escape our fire … .

1.2. Whalers, sealers and traders

By the early decades of the nineteenth century, small numbers of whalers, sealers, traders and other Europeans had established a permanent presence in parts of coastal New Zealand, especially in Northland and the deep south. Escaped convicts from Australia, runaway sailors and other ‘rough’ characters were prominent among their number, and the early colonial frontier was often a brutal place. Maltreatment or exploitation of Māori was frequent. Eager to engage in trading and other opportunities, Māori often responded to these insults with remarkable restraint. The killing of most of the crew and passengers of the sailing ship the Boyd in December 1809 in response to one incident of abuse was a notable exception. Most of the small number of European men who chose to settle in New Zealand at this time found a degree of protection through intermarriage with Māori women. But incorporation into the tribe brought its own obligations to actively contribute towards the welfare of the community.

1. Mistreatment of Māori sailors results in destruction of the Boyd

Samuel Marsden, ‘Observations on the Introduction of the Gospel into the South Sea Islands: Being my First Visit to New Zealand in December 1814’, in Robert McNab (ed.), Historical Records of New Zealand, 2 vols, Government Printer, Wellington, 1908, vol. 1, pp. 356–57.

I made a few presents to the chiefs, and after some conversation on various subjects … I enquired how they came to cut off the “Boyd” and to murder the crew. Two of them stated that they were at Port Jackson when the “Boyd” was there, and had been put on board by a Mr. Lord in order to return home – that George (their head chief) had fallen sick while on board, and was unable to do his duty as a common sailor, in consequence of which he was severely punished – was refused provisions, threatened to be thrown overboard, and many other indignities were offered to him, even by the common sailors. He remonstrated with the master, begged that no corporal punishment might be inflicted on him, observing that he was a chief in his own country, which they would ascertain on arrival at New Zealand. He was told he was no chief, with many abusive terms which he mentioned, and which are but too commonly used by British seamen. When he arrived at Whangaroa his back was in a very lacerated state, and his friends and people were determined to revenge the insult which had been offered to him. He said that if he had not been treated with such cruelty the “Boyd” would never have been touched.

2. Abuse of Māori acknowledged in official proclamation

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 18 December 1813.

WHEREAS many, and, it is to be feared, just Complaints have been lately made of the Conduct of divers [sic] Masters of Colonial and British Ships, and of their Crews, towards the Natives of New Zealand, of Otaheite, and of the other Islands in the South Pacific Ocean: And whereas several Ships, their Masters, and Crews, have lately fallen a Sacrifice to the indiscriminate Revenge of the Natives of the said Islands, exasperated by such Conduct … .

Figure 2. Te Matenga Taiaroa was (along with Tuhawaiki) one of the leading Ngāi Tahu chiefs who played a pivotal role in welcoming European traders and sealers to the southern districts in the pre-Waitangi era. auguste jagerschmidt, ‘tairoa [sic], king, otago’, 1841, rex nan kivell collection, nk10377/2, national library of australia

3. Māori demonstrate remarkable restraint in many circumstances

Augustus Earle, A Narrative of a Nine Months’ Residence in New Zealand, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman, London, 1832, pp. 253–54.

I once saw, with indignation, a chief absolutely knocked overboard from a whaler’s deck by the ship’s mate. Twenty years ago so gross an insult would have cost the lives of every individual on board the vessel; but, at the time this occurred, it was only made the subject of complaint, and finally became a cause of just remonstrance with the commander of the whaler. The natives themselves … have invariably told me that these things occurred from our want of knowledge of their laws and customs, which compelled them to seek revenge. “It was,” they said, “no act of treachery on our part: we did not invite you to our shores for the purpose of plunder and murder; but you came, and ill used us: you broke into our tabooed grounds. And did not Atua give those bad white men into the hands of our fathers?”

4. Early European residents deemed ‘refuse’

John Dunmore Lang, New Zealand in 1839, or, Four Letters to the Right Hon. Earl Durham, Governor of the New Zealand Land Company … On the Colonization of that Island, and the Present Condition and Prospects of its Native Inhabitants, Smith, Elder & Co., London, 1839, p. 3.

With a few honourable exceptions, it consists of the veriest refuse of civilized society – of runaway sailors, of runaway convicts, of convicts who have served out their term of bondage in one or other of the two penal colonies, of fraudulent debtors who have escaped from their creditors in Sydney or Hobart Town, or of needy adventurers from the two colonies, almost equally unprincipled.

5. Charles Darwin is also unimpressed

Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, 2nd edition, John Murray, London, 1845, p. 430.

In the afternoon we stood out of the Bay of Islands, on our course to Sydney. I believe we were all glad to leave New Zealand. It is not a pleasant place. Amongst the natives there is absent that charming simplicity which is found at Tahiti; and the greater part of the English are the very refuse of society. Neither is the country itself attractive.

6. But Māori curiosity remains

John Logan Campbell, Poenamo: Sketches of the Early Days of New Zealand. Romance and Reality of Antipodean Life in the Infancy of a New Colony, Williams & Norgate, London, 1881, p. 162.

The fact that Kanini had bagged a brace of Rangatera Pakehas became known from one end of the Hauraki to the other in just about as short a time as if there had been telegraph stations the whole way. The result was that a stream of visitors set in in a strong current to rub noses with the old man – ostensibly to do this, but in reality to satiate their curiosity in having a look at us and hearing all about us, and to whom we were to be married was, of course, a point of intense interest.

Now every time any of these visitors came we had no choice but to gratify their curiosity by turning out for inspection. But inasmuch as we only knew Maori enough to the extent of being able to say “Tena koe?” (“How do you do?”), and as that terminated our conversational powers in their vernacular, nothing then was left us but to stare at each other. In this little part of the performance we had no chance against our new friends, who beat us hollow at it. Sitting squatted on the ground, rolled up in their mats, or last new blanket donned for the occasion, they had a power of endurance which put to shame us poor civilised creatures.

7. Frederick Maning explains the obligations of a Pākehā-Māori towards his chief

Frederick Maning, Old New Zealand; A Tale of the Good Old Times, Robert J. Creighton and Alfred Scales, Auckland, 1863, pp. 180–82.

Firstly.- At all times, places, and companies, my owner had the right to call me “his pakeha.”

Secondly.- He had the general privilege of “pot-luck” whenever he chose to honour my establishment with a visit; said pot-luck to be tumbled out to him on the ground before the house, he being far too great a man to eat out of plates or dishes, or any degenerate invention of that nature; as, if he did, they would all become tapu, and of no use to any one but himself, nor indeed to himself either, as he did not see the use of them.

Thirdly.- It was well understood that to avoid the unpleasant appearance of paying “black mail,” and to keep up general kindly relations, my owner should from time to time make me small presents, and that in return I should make him presents of five or six times the value: all this to be done as if arising...