This is a test

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Globalisation and the Wealth of Nations

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Neither an argument for nor against globalization, this book is a careful and thorough analysis of the issues of globalization and an imaginative, wide-ranging picture of the globalizing world. It aims to both inform and enable readers to improve their own decisions about how to harness globalization, the economic theory behind it, the political and social consequences, and the various options for nations in a globalized world. Case studies aid in the exploration of this largely unstoppable but governable force in the world today.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Globalisation and the Wealth of Nations by Brian Easton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Globalisation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Diminishing Distance

One

Globalisation • An Introduction

This book is underpinned by five propositions about globalisation:

- Globalisation is the economic integration of regional and national economies.

- It is caused by the falling cost of distance.

- It has exceptionally powerful effects when the reduced costs of distance combine with economies of scale.

- It first became important in the early nineteenth century.

- It is not solely an economic phenomenon in a historical and geographical context. It has political and social consequences. In particular, it impacts on, but does not eliminate, cultural differences, and it reduces, but does not eliminate, the policy discretion of nation-states.

I will introduce the book by elaborating on each proposition. (Chapter 20 gives a brief introduction to the standard theory of economic growth.)

1. Globalisation is the economic integration of regional and national economies.

It is possible to write an entire book on globalisation without defining the term. Fortunately, in recent years economists have moved towards a common definition, although the one used here is slightly wider because it includes regional as well as national economies. From a historical perspective, the integration of nations was preceded by the integration of regions. The standard economic definition presupposes that regional integration is no longer important. But there are four reasons why regions still matter.

First, we can learn much about national integration by studying regional integration. Second, regional integration and relocation is still going on within nations. And we must also explain the role of cities, intensely local phenomena which are nevertheless integral to globalisation. Additionally, two regional integrations provide possible models for the future world economy. The US economy may be thought of as an early example of a mini-globalised world in which states are not very powerful. The European Union is a more recent mini-globalised world in which states have retained more authority. Each offers a possible system of world economic arrangements, a topic explored towards the end of the book.

2. Globalisation is caused by the falling cost of distance.

Comprehending globalisation requires an understanding of the role of space (geography) in economics, for economic space is connected by the costs of distance. These are much more than transport costs. They include the costs of storage, security and insurance, information transfer, timeliness and those arising from lack of intimacy.

A quantitative indication of their significance can be found in a study of paper trade costs by James Anderson and Eric van Wincoop.1 They calculate that the average American manufacture incurs a mark-up of 55 per cent between the factory door and the domestic consumer. This covers such things as shipping, storage and the retailer’s margin. But for exports the total mark-up is 170 per cent. On average a product going out an American factory door worth $100 sells in America for $155 and overseas for $270. One might associate the 55 per cent mark-up with regional trade costs, and the 74 per cent mark-up from $155 to $270 with international trade costs.

Clearly trade costs are a large part of the cost to a purchaser. Actual figures vary greatly on the basis of both destination and product. A Barbie doll manufactured in Asia for $1 sells for $10 in the US, a mark-up of 900 per cent.

Anderson and van Wincoop attribute about a third of the export trade costs (the 74 per cent mark-up) to transport costs – both the costs of direct freight and the time value of goods in transit. The other two-thirds are incurred by border-related barriers – barriers raised by differences of language, currency and information; the costs of contracting and insecurity; and barriers erected by policy (both tariff and non-trade). Policy barriers contribute just a seventh of export trade costs, less than currency barriers, freight costs and the time value of goods in transit, and only slightly greater than information and language costs.

Tariffs are treated here in a similar manner to any other cost of distance. Economists have a substantial theory on tariffs (which largely ignores costs of distance). Converting these other costs into tariff equivalents means that the economic theory applicable to tariffs also applies in most respects to these costs.2

Despite this insight, an investigation of the consequences of distance is not high among economists’ priorities. An American textbook which I greatly admire, Paul Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld’s International Economics: Theory and Policy,3 devotes just two pages of more than 750 to transport costs. In contrast, there are some 40 pages on tariffs, even though these are such a small proportion of total trade costs. This is all the more surprising, given that Krugman is one of the pioneers of the modern theory of spatial relationships in economics.

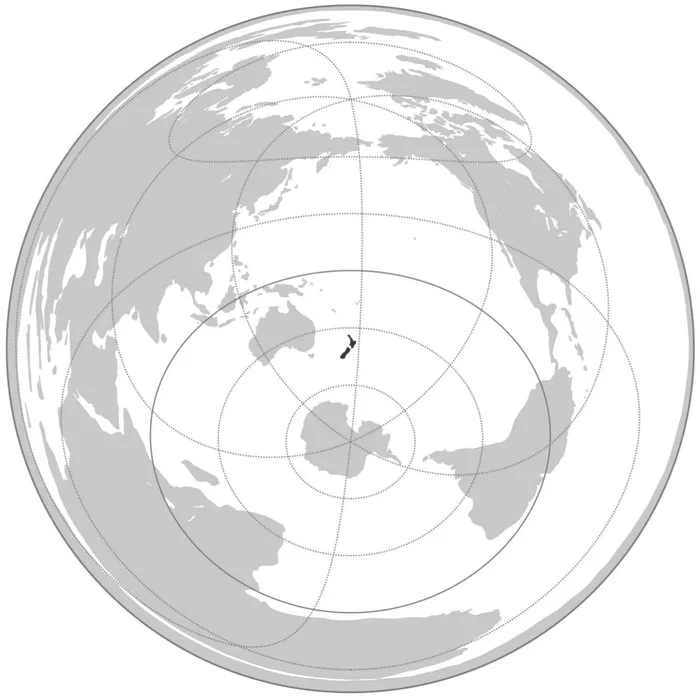

New Zealand’s world 150 years ago

Throughout the book we will see examples of the dramatic fall in trade costs over the last two centuries. (There is no comprehensive study of the extent of this decline.)

Geoffrey Blainey entitled a history of Australia, The Tyranny of Distance (and New Zealand was even further away from the places that mattered). But effective distance has been changing. In the early nineteenth century it took the Brontë sisters a couple of days to get from their Yorkshire vicarage to London, longer than it takes today’s Australasians to fly in from the other side of the globe.

Because the phenomenon has so many dimensions, and because it applies to so many things – different products, people, information – it is difficult to illustrate the falling costs of distance except by giving examples. One study suggests that the cost of ocean shipping relative to general prices fell by more than 86 per cent between 1790 and 1990.4 Even this figure does not allow for the additional savings from trips becoming shorter and safer (or for declining wharf costs).

Time is money – and easier to measure. The travel time between New Zealand and England has fallen dramatically over the last 150 years. In the mid-nineteenth century it took a boat three to four months to sail from New Zealand to England, then the centre of its economic world. Imagine that effective distance is symbolised by the circle shown on the opposite page with the diameter of the width of this page.

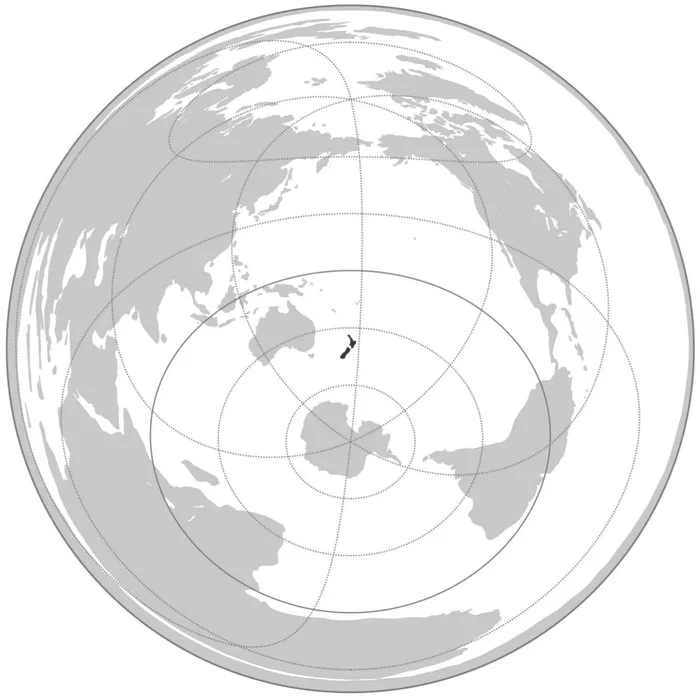

Today a boat – faster (and safer) and using the Panama Canal – can do the trip in three to four weeks. The circle now, shown below, has a diameter of a quarter of the width of the page.

New Zealand’s shipping world today

Even this underestimates the reduction. While goods largely go by ship, nearly a fifth of New Zealand’s merchandise exports and imports are now airfreighted. Most people fly to and from New Zealand. A direct flight to England takes just over a day. Relative to the time it took 150 years ago, this takes up almost no width on the page.

New Zealand’s air travel world today

Information travels even faster. It can be electronically transferred between New Zealand and England (or just about anywhere else) almost instantaneously. Whereas a nineteenth-century letter was carried by ship right across our notional page, today’s travel time is smaller than the full stop which ends this sentence.

There are many more instances of this dramatic reduction in effective distance. However, while the tyranny of distance has diminished, reports of its death are exaggerated. The world itself is not a full stop.

Nor has the shrinkage been uniform. Costs have diminished at different rates for different sorts of goods and services, for people, and for information. Tariff theory predicts complex outcomes where tariffs are not reduced to zero and the reductions are not proportional. In fact, a partial reduction in some tariffs can make an economy worse off.5

Once the point of the importance of costs of distance is grasped, it is astonishing how often one observes their significance – and how often others do not. Chapters 2 (Samoa and Hawaii) and 3 (refrigeration in New Zealand) illustrate how much the world can change when costs of distance change. Which leads us to the next proposition.

3. Globalisation has exceptionally powerful effects when the reduced costs of distance combine with economies of scale.

Economists often assume that producing more requires an increasingly greater effort, a notion captured in the phrase ‘diminishing returns’ and signalled by rising unit (or average) costs as output in a fixed time period increases. This is perhaps no more than an example of the laws of thermodynamics. The introduction of a new technology may mean that more can be produced for less (at a lower cost), but for a particular technology it is usual for diminishing returns to apply.

However, over some ranges of production, unit costs may fall. The second item usually costs less to produce than the first. But the unit costs of some processes continue to fall even within the normal range of production. The reasons for economies of scale are numerous. They include indivisible inputs (as when a machine costs the same whether it produces a single item or many); start-up costs; learning effects; specialisation; the economies of increased dimensions (insofar as the thickness of the wall of a tank is fixed, its cost rises with the square of its dimensions, but its capacity with the cube); greater use of flow production rather than batch production; smaller inventories; the division of labour. Any short list is inevitably incomplete.

Economies of scale are important in economic growth (and are frequently realised when the costs of distance fall). But they generate some deep analytic problems for economists. It would take another book to explain them in detail to a lay audience – and the explanation may be so complex that this book cannot be written. A central problem is that once there are economies of scale the standard account of competitive markets does not work properly. While markets will continue to produce and distribute products, they may no longer do so efficiently, using the minimum of resources.

Once there are economies of scale odd things can happen – or do they just seem odd because we are so familiar with the outcomes of the standard model? It may be that we so often use the assumption of diminishing returns that outcomes caused by other factors strike us as unusual. Yet the reality may be the other way around. It was appropriate for economists to focus initially on diminishing returns. Having got that analysis broadly right, in the last quarter-century they have moved on to more analytically complicated cases in which there are increasing returns.

In particular, falling costs of distance enable economies of scale to be reaped. The theory is superbly developed in The Spatial Economy: Cities, Regions and International Trade, by Masahisa Fujita, Paul Krugman (again) and Tony Venables (‘FKV’). Do read this book if you are able. But be warned: it is based on mathematical models, some of which are quite challenging – even for its authors.

An illustration may be useful at this point. Suppose that steel mills have enormous economies of scale, so that the unit cost for large production is very much lower than when production is small. If costs of distance are high, the mill’s market may be local, and so small that no steel is produced and the locality – and all localities – has no access to cheap steel. Now suppose the costs of distance fall. The potential market increases to the point that it is commercially viable to supply it from one large plant. A whole range of uses – many hitherto unknown – appear. As we will see in Chapter 4, the forces unleashed may be powerful, dynamic and transformational.

The results can be unexpected. In Chapter 6 we see that the location of an industrial plant with large economies of scale is determined by luck and history. (The phenomenon could also be illustrated for cities in Chapter 5, but here the principle of agglomeration effects – industry economies of scale – is the focus.) Later in the book there is an account of the world economy. Because of economies of scale, countries go down one of two distinct development paths: one in which the economy benefits from economies of scale (the Rich Club), and one in which it does not (the Poor Club), with hardly any countries in between. The result is both a powerful account of the history of the world economy and an extraordinary – yet plausible – suggestion of how it may develop in the future.

Subsequent chapters in Part I extend the underlying notions to intraindustry trade, services in international trade and migration.

4. Globalisation first became important in the early nineteenth century.

There is much argument as to when the processes of globa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Prologue

- Preface : Yet Another Book on Globalisation?

- A Note on Statistics

- Acknowledgements

- Part One : Diminishing Distance

- Part Two : The Nation-State and Diminishing Distance

- Part Three : Economic Development

- Part Four : The Future

- Epilogue : Democracy in a Globalised World

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright