![]()

![]()

| 1 | Cairo as Neoliberal Capital? |

| From Walled City to Gated Communities |

Eric Denis

Insecurity and a Land of Dreams

Ahmed Ashraf al-Mansuri will not be slowed down too much by traffic this evening.1 His chauffeur is without equal for sinuously extricating him from the agitation of the inner city. Blowing the horn and winking to the police, the driver climbs up the on-ramp and merges onto the new elevated beltway. He dashes quickly westward, toward the new gated city in the once-revolutionary Sixth of October settlement. Without so much as a glance, Mr. al-Mansuri has skimmed over that unknown world where peasants are packed into an inextricable universe of bricks, refuse, self-made tenements, and old state housing projects. When it occurs to him to turn his head, it is to affirm that he has made the right choice in moving far away from what he thinks of as a backward world that remains a burden for Egypt, and that diminishes and pollutes the image of Cairo. He knows that he has again joined the future of Egypt. At any moment, he thinks, this crowd could mutate into a rioting horde, pushed by who knows what manipulating sheikh’s harangue.

Neither the heat, nor the muffled noise of the congested streets has penetrated his air-conditioned limousine. Ahmed Ashraf al-Mansuri considers the prospect of a round of golf, followed by a discussion at the club house with his friend Yasin from the Ministry of Finance, then a short stroll home. The stress of his day is already fading away.

Since 8 AM, shadows had begun to haunt Ahmed as he looked out from the eleventh-floor windows of the Cairo World Trade Center dominating the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and looming over the corniche that lines the Nile River. He is experiencing a downturn in his business transactions—that important monopoly on ice cream was not granted to him and the opportunity to buy an apartment building escaped him. ‘Risky’ remains his watchword. Would that it were owing only to this currency devaluation of which no one knows the way out, or the disappearance of foreign exchange. Fortunately, he has obtained a respectable distribution contract with an international chain of hotels to buy his cartons of milk that he packages in his small factory. He will have to go there tomorrow to accelerate production before going to the office. He has hardly the time to call his son who is in his third year in political science at SOAS (the School of Oriental and African Studies) in London. But in his car his anxieties fade away as he commutes away from downtown Cairo, past the Pyramids, into the desert. Then Mr. al-Mansuri arrives home, entering the gates of his new residential community, Dreamland.

There he passes Abu Muhammad, his usual caddy who, having finished his day, is waiting for the minibus that will take him to his small apartment of forty square meters, shared with some ten other waiters and workers living in the oldest quarters of the town of Sixth October, farther to the west on the desert plateau. His wife and children, having never migrated to the capital city, have remained in the village near the city of Mansura in the Delta.

The wife of Ahmed Ashraf al-Mansuri has not been to Cairo for more than two weeks. She comes only to visit a female cousin in Utopia, a near-by gated community. After her foray to the shopping center, she is late picking up her children. They are returning from an afternoon at the amusement park with Maria, the Ethiopian maid. The children are playing now in the pool, watched over by Mahmoud, the security guard. Maria, the Ethiopian maid, knows that she will return to her room—a small room without windows behind the kitchen—but only later that evening. There are the guests; she will have to help the cook after putting the children to bed.

New Risks and Privatized Exclusivity

With the above fictionalized narrative, we arrive on the desert plateaus bordering the city and suburbs of Cairo. To the east and to the west, for a dozen or more years, promotion of the construction of private apartment buildings has led to the acquisition of vast expanses of the public domain, putting them in the hands of development contractors. More than one hundred square kilometers are actually under construction, that is to say, a surface equivalent to more than a third of the existing city and suburbs, which has been fashioned and refashioned among the same founding sites for a thousand years. Dozens of luxury gated communities, accompanied by golf courses, amusement parks, clinics, and private universities have burgeoned along the beltways like their siblings, the shopping malls. (See Abaza, and Elsheshtawy (chapter 7) in this volume for analysis of the growth of luxury malls in Cairo.) Against an extremely compact ‘organic’ urban area, the model for the dense, non-linear ‘Asiatic’ city analyzed by orientalist geographers, is juxtaposed against the horizon of a new city more like Los Angeles, gauged from now on according to the speed of the automobile. This new dimension of Cairo is marked by a flight of the urban elites made more visible by the de-densification of the urban center.2 This radical reformulation of the metropolitan landscape, which its promoters invite us to view as an urban renaissance or nahda ‘umraniya, is completely in tune with the parameters of economic liberalization and IMF-driven structural adjustment.

To be sold, the gated communities brandish and actualize the universal myth of the great city where one can lose oneself in privatized domestic bliss. Promoters exploit more and more the stigmatization of ‘the street,’ spread by the media on a global scale, and finally of the Arab metropolis as a terrorist risk factory that is necessarily ‘Islamic.’ Far from being rejected, the Islamist peril is exploited by the Egyptian authorities to legitimize political deliberalization, while it promotes a particular landscape of economic restructuring. The current regime redirects and displaces the urgency of law and the immediate interests of Egypt’s elites through the affirmation of market and security systems, of which the gated communities are a prominent feature.

Within this optic, the gated communities must appear as a privileged window onto the reality of liberalization in Egypt. Analysis of these settlements allows one to understand how mechanisms of risk control impose social exclusion (the reverse side of elitist globalization) and how they define the risks themselves. Urban ecology and the priorities of security are reversed to favor suburban desert colonies: defensive bastions against the lost metropolis. At the heart of this reversal, global/local developers and state agencies play out the transfer of power to businesspeople associated with the construction of a new hybrid, globalized Americano-Mediterranean lifestyle.

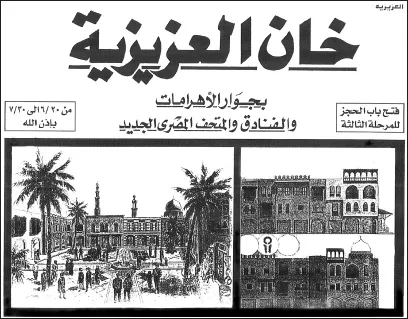

Advertisement for a new gated community in Cairo that appropriates neoorientalist/Islamic models, (al-Ahram 1996, n.d.).

At the center of this new way of life are Egypt’s elites, themselves connecting together the archipelago of micro-city communities that they administer as if they were so many experimental accomplishments of a private democracy to come. The gated communities, like a spatial plan, authorize the elites who live there to continue the forced march for economic, oligopolistic liberalization, without redistribution, while protecting themselves from the ill effects of its pollution and its risks. In the same way, these elites rejoin the transmetropolitan club of the worldwide archipelago of walled enclaves (Caldeira 2000). The potential guilty anxieties relative to the suffering of ordinary city dwellers are, then, masked by global rejection of the city, according to an anti-urban discourse that incorporates and naturalizes pollution, identifying it with poverty, criminality, and violent protests against the regime. In this elite perspective, Cairo has become a complex of unsustainable nuisances against which nothing more can be done, except to escape or to protect oneself. Urban risk, and, by the same token, urban ecology, are radically recomposed.

In the rest of this chapter, I will trace the material development of the gated communities, their promotion and appropriation. Then I will identify the risk discourses that create the foundation for, and enable the legitimation of, the renewed management of social distances. But first, it is appropriate to define what we mean by fear, risk, myth, and urban ecology.

Contouring Risk and Legitimacy in the Landscape

Risk is understood as a social and political construct that crystallizes, sorts, and normalizes dangers, fears, and anxieties that define and limit a given society (Hacking 2003). The formulation of risks allows one to focus on modalities of individual and collective action, and to determine strategies of habitation, in order to protect integrity and the sense of being among one’s own, or, simply, diversity control. As places in which diversity and coexistence are maximized, metropolitan areas are, in their material, social, and political expressions, the product of responses and reactions to the dangers that are negatively associated with density and diversity. Dimissive fears, like those associated with pollution, nourish the procedures of self-definition and delimitation of a city community. They facilitate the creation of ‘society’ (Douglas 1966; Douglas and Wildavsky 1982). Like marginalities, fears define borders. They lie at the heart of the interactionist formulation of identity as relationships of domination.3

The specter of risks, projected through media and representational structures, normalizes collective fears (Weldes et al. 1999). It claims to validate legitimate worries and put aside superstitions that appear as backward. This work of definition authorizes a system of protection of individual or collective control, and the establishment of norms and institutions, such as insurance, legislation, armed forces, police, medicine, borders, architecture, urban planning, etc. Measures taken to acknowledge risk aim at replacing chance occurrences with predictable events.

Always present is the myth of the urban Babylon, portrayed as a prostitute and as a place of potentially unfathomable corruption and loss. As always, this image serves to reify diffuse anxieties that threaten the stability of a regime embedded in urban order. Risk myths allow the legitimation of borders and of territorial command. The definition of risk enters into the heart of procedures that stigmatize subordinate groups, designate ‘scapegoats,’ and map illegitimate territories (Girard 1982). It lies at the foundation of the designation of clandestine transients—those who do not have their place in the city and must be kept at a distance because they threaten its harmony.

It is, therefore, more than coincidental that, precisely in Egypt, the word ‘ashwa’iyat, which derives from the Arabic root that signifies chance, appeared at the beginning of the 1990s to designate slums, shantytowns, and the selfmade satellite cities of the poor, i.e. illegal and/or illegitimate quarters. By the end of the 1990s, the term came to describe not just spaces but peoples, encompassing a near-majority of the city as risky, ‘hazardous,’ errant figures. The figure of the errant is that which most frightens this urban society. Seen as the invading silhouette of the decidedly peasant migrant from the provinces, the fallah (peasant) frightened and still frightens urban society. This designation also reanimates the classic Muslim opposition between the fallah and the hadari (the urban or ‘civilised’), and between settled and nomad communities.

Today Egypt’s globalizing metropolis finds itself at a point of instability, swaying between a society in which fatalism and malediction play a major role in the management of crises and catastrophes, and the ‘society of risk’ characterized by a lack of certainty, in which it becomes impossible to attribute uncertainty to external or ungovernable causes. In reality, the level of risk depends on political decisions and choices. It is produced industrially and economically and becomes, therefore, politically reflexive. Egypt, however, analyzed from the perspective of Ulrich Beck, reminds us that old modernization solutions are untenable, because religious radicalism and authoritarian practices are growing, but are always attributed to foreign plotting, denying the development of a reflexive national public and repressing internal debates (1992). In this context, risk remains an ambivalent object that produces exclusionary norms while ancestral myths and beliefs are reappropriated and remade in order to master and stabilize current forms of political monopoly.

Gated communities are one of the most striking and revealing products of this new ecology of risk and monopolization of politics. They reveal processes of disorganizing and reorganizing modes of living and cohabiting in the city, that is, the dynamics of spatializing a new neoliberal ‘moral order’ and justifying it through risk discourse (Park 1926).

The New Liberal Age and the Material Framework of Colonial Nostalgia

The state’s offering of a new exclusive lifestyle ignited an explosion. From 1994, when the Ministry of Housing began on a massive scale to sell lots on the desert margins of Cairo, the number of luxury construction projects very quickly surpassed market absorption capacity. The region of Greater Cairo includes a limited number of middle-class families; not more than 315,000 families’ current expenses exceed LE2,000 per month ($350 in 2005 dollars). And these are counted as the 9.5 percent most wealthy.4 Yet within this limited market, 320 companies have acquired land and declared projects that, in potential volume, total six hundred thousand residences.5 In the first years since the boom, no less than eighty gated city projects have been erected, with many sectors presold, and the first families settled. In 2003 alone these companies put some sixty thousand housing units of villas and apartments on the market. Where will all these rich families come from?

Utopia, Qattamiya Heights, Beverly Hills, Palm Hills, Belle Ville, Mena Garden City, Dreamland: these are some of the gated communities under development. These developments are marketed as the cutting edge of a post-metropolitan lifestyle, invented between the imaginaries of ‘fortress America’s’ sprawling cities and the new risk-apartheid of Johannesburg (Blakely and Snyder 1997). However, if the ensembles of villas respond perfectly to the global concept of the protected city, encircled by a wall and assuring a totally managed autonomy, this is not just an importation of a universal model. Th...