![]()

1 Coptic Ostraca from Hagr Edfu

Anke Ilona Blöbaum

WHILE THE GREEK AND COPTIC documentary texts of late antique Tell Edfu are well represented in the scientific discourse,1 very little information is known about comparable material from Hagr Edfu. In fact, a number of Greek and Coptic ostraca have been located in Hagr Edfu as well.

In the year 1941, a number of Coptic and Greek ostraca were found near the ruins surrounding the nineteenth-century church. Unfortunately they were never published and their whereabouts remains unknown (Fakhry 1947: 47; Gabra 1985: 11; 1991: 1200; Effland 1999: 25).

Forty years later, during an excavation conducted by the inspector of Edfu at that time, Mohamed Ibrahim, another large number of ostraca were discovered at the site. They were found near the northern wall of the modern monastery, Dayr Anba Bakhum (Monastery of St. Pachomius). These ostraca were previously mentioned by Gawdat Gabra (1985: 12; 1991: 1200), Andreas Effland (1999: 29), Anne Boud’hors (1999: 4), and Elisabeth O’Connell (Davies and O’Connell 2009: 56f.; 2011: 106). They are currently the focus of an editing project associated with the Institute of Egyptology and Coptology at the University of Münster, Germany.2

The following short overview of the material is based on the photographic documentation undertaken in the year 1981 during the excavation.3 The corpus consists of approximately 180 ostraca. Ten of them are inscribed on recto and verso. As most of the material is broken into pieces, the number of fragments is accordingly higher. It is possible to join several fragments. The size of the ostraca and state of preservation of the texts differ greatly, from tiny fragments measuring not more than three centimeters in height and width, with only a few words or even letters, to completely preserved ostraca measuring more than twenty centimeters in height or width. Most of the texts are Coptic, only two (or possibly three) ostraca are Greek without a doubt;4 due to their state of preservation, the language and script of approximately a dozen other pieces are difficult to assess.

The types of hands vary. They show a whole spectrum from inexperienced hands to very skillful writing using ligatures. So far, it has been possible to assign only two ostraca to the same (unnamed) scribe with confidence. Unfortunately, only set phrases of the beginning of a letter are preserved on both fragments.

Indeed, most of the texts are letters (for issues of letters and genre, see Choat 2006). Only a few pieces do not belong to this genre. Phraseology and titles clearly set the corpus into a probable monastic context. It seems to be the correspondence of a relatively small community of monks or people related to a monastery and a settlement located nearby (cf. Boud’hors 1999: 4; Davies and O’Connell 2009: 56). This differs from the mainly economic and administrative character of the Greek and Coptic documentary texts from Tell Edfu (Boud’hours 1999a: 4).

The dialect is mainly Sahidic. Particular dialectal forms can be related to the variations of the language in the Coptic texts of Tell Edfu (cf. Bacot 2009: 5ff.). Personal names, like Abraham, Victor, Jacob, Dios, or Kolluthos, find parallels in the epigraphic evidence of Hagr Edfu (O’Connell in Davies and O’Connell 2009: 56), and in the Greek and Coptic texts of Tell Edfu (cf. Bacot 2009: 198ff.; Remondon 1953: 225ff.). But this common Onomasticon gives no further results. Specific persons or places are not identified yet. The subjects of the letters deal mainly with personal concerns, mostly in connection with requests. Difficulties and questions concerning, for example, payment, rent, and delivery of goods such as bread, oil, clothing, and papyrus are described.

As mentioned above, most of the texts contain letters, or rather letter fragments. Only a few texts do not belong to this group. Three of them form a small unit of their own because they all belong in a context of education and writing practice (for Greek school text, see Cribiore 1996; for Coptic, see Cribiore 1999).

There are at least three other ostraca that could possibly also be classified as writing exercises, because the hands seem unskillful and inexperienced, and the orthography is incorrect. But in each case the preserved text is characteristic of a letter, thus making it difficult to decide whether it could be an exercise for a letter or a real letter written by a scribe lacking experience. Without additional clues, I prefer to omit these texts in the following presentation.

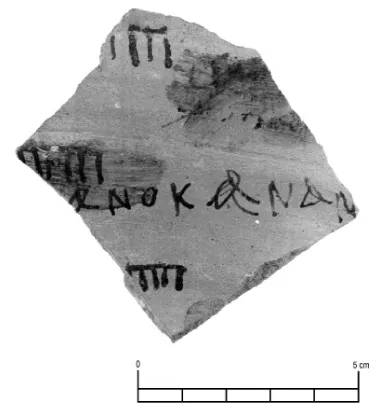

1. Fragment of a writing exercise: grouped lines and isolated words5

The first exercise is written on a small fragment of pottery (h: 8 cm, w: 7.5 cm). The left margin of the ostracon is incomplete. Parts of four lines are preserved. Three of them consist of groups formed by vertical and horizontal lines (ll. 1, 2, and 4) and the third of two single words. The sherd was reused: in the upper half, two text groupings have been rubbed out. One part (between lines 1 and 2 on the right) was left blank. The group in line 2 and the beginning of line 3 are written over the other cleaned part. In all probability this was done by the same student.

The hand is very unskilled. The groups of lines seem to form rows of the letter

, but a closer look reveals that it is more a general exercise of writing horizontal and vertical lines than practice of isolated letters. In each case a long continuous horizontal line on the top is combined with three to six vertical lines. Maybe this was a first step of practice before starting to write isolated letters. But the student skipped this next step. Instead of isolated letters, the writer attempted two words:

and

(l. 3). The letter

, in particular, shows a lack of practice. In one case the student had to rewrite the letter twice. Obviously this is an exercise of a writer who has just started to learn.

Fig. 1.1 Writing exercise: grouped lines and isolated words (D. Johannes)

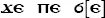

2. Ostracon with writing exercise: isolated letters and syllables

The second ostracon with a writing exercise seems almost completely preserved (h: ca. 8 cm, w: ca. 6.5 cm). Only the right margin is probably incomplete. The edges are worn and at the upper left a small part of the surface is damaged. The hand is more skillful than the one in

figure 1.1, but still gives the impression of inexperience. It is very difficult to recognize any structure or pattern in the text, or, rather, the scrawl, because the student wrote several times on the sherd without first making erasures. As a result, the upper part is not very clear or legible. At least eight lines can be recognized. Three of them were probably written first, the five others over them. It is also possible that a fragment of a non-practice ostracon was reused. Because the whole text in every discernible layer was obviously written by the same hand, this option is not very plausible. The more legible traces give the impression of a student’s exercise of isolated letters, with a special focus on

, and probably also syllables. In the last two lines, for example,

(?), and

(?) are recognizable.

Fig. 1.2 Writing exercise: isolated letters and syllables (D. Johannes)

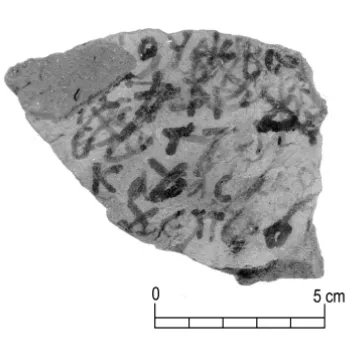

3. Ostracon with writing exercise: isolated letters, syllables, set phrases, and book-hand

The last of the three writing exercises is an almost completely preserved ostracon (h: ca. 19 cm, w: ca. 11 cm) that shows four different types of training. The hand is very skillful and practiced. Unfortunately the text was rubbed out, so that only some of the content is recognizable. These traces can be divided into four different parts. The first part consists of eleven or twelve lines, most of which were damaged by the cleaning. The words

and

give the impression that the writer had worked on formulating a letter. It is also possible that he reused an ostracon with an old letter for his exercise. In any case, it is clear that all the text was written by the same hand. Thus its identification as an exercise

is more probable.

6 The second part is located below the first. Consisting of three lines, it shows an exercise of a book-hand. The text does not make much sense but this could be because of the damage. Apparently the scribe was concentrating more on forming particular letters, and he did this quite succ...