![]()

At one level, the accession of Merenptah was marked by the addition of a uraeus to the brow of a number of his princely representations,1 and of a new column of text with his kingly titles to the monumental processions of the royal sons in the Ramesseum (fig. 5).2 At another, it provided the world with its first new king of Egypt for nearly seven decades—a world that was changing fundamentally from that which had existed at the accession of Merenptah’s father.

Merenptah adopted the wholly new prenomen Baenre (

n , “Soul of Re”), plus the alternate epithets “beloved of Amun” (

mry-’Imn— or

) and “beloved of the gods” (

). For a nomen, he added to his birth name the epithet “satisfied with Truth” (

, and minor orthographic variants).

3 The remainder of Merenptah’s titulary showed wide variation between monuments and locations, demonstrating the transition seen during the New Kingdom from the Horus, Nebti, and Golden Falcon names being true and generally immutable “names,” to their becoming little more than epithets.

4The King’s Great Wife was a certain Isetneferet (C). An early assumption was that she was none other than Merenptah’s full blood sister, Isetneferet (B), but nowhere does the queen bear the expected resulting titles “King’s Daughter” or “King’s Sister.” Accordingly, it has been suggested that Merenptah might have espoused the like-named daughter of Khaemwaset C, that is, the king’s niece.5 However, this cannot be proved and it is quite possible that she was of non-royal birth, married to Merenptah long before he had any thought of succeeding to the throne. Isetneferet C is shown on a pair of stelae in the Eighteenth Dynasty rock temple of Horemheb at Gebel Silsila (fig. 12),6 as well as in Merenptah’s own shrine there (fig. 23)7 and on the back pillar of a usurped statue of Amenhotep III at Luxor temple.8 A companion piece has the king’s sister Bintanat in the same location; whether this indicates that Merenptah espoused Bintanat, or simply reflects Bintanat’s position as a queen dowager of her father, Rameses II, is uncertain.9

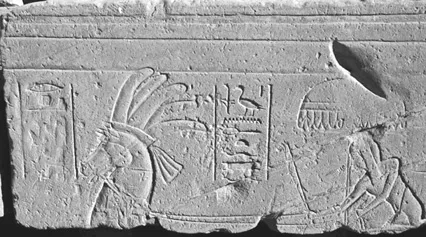

Fig. 12. Merenptah, Isetneferet, and Sethy-Merenptah A offer to Ptah on a stela inscribed at Gebel el-Silsila by the vizier Panehsy.

Of the offspring of Merenptah and Isetneferet, his ultimate heir, Sethy-Merenptah (A),10 is well known from a broken statuette,11 a number of his father’s statues,12 stelae at Gebel el-Silsila,13 his father’s battle reliefs (fig. 13),14 a notation of the verso of the Papyrus d’Orbiny,15 and possibly a column-drum.16 A further son, Khaemwaset (D), is shown in the king’s Palestinian war reliefs at Karnak (fig. 14; see below),17 while a daughter, Isetneferet (D), may be named in another papyrus.18

The possibility that Merenptah had a third son is raised by five monuments that clearly belong together. They name a prince Merenptah (B) whose titulary differs but slightly from those borne by Merenptah himself before he acceded to the throne (lacking perhaps most significantly “Eldest King’s Son”), and like him with uraei added to their brows.19 Most crucially, two of these monuments are statues of Senwosret I, usurped (apparently for the first time) by Merenptah as king, at which time the prince’s inscriptions seem also to have been added.20 Since Merenptah is hardly likely to have taken over the statues to make them represent himself as king, and also show himself in his former status as a mere prince on the same monuments, the presence of uraei on the brows of the latter images is distinctly problematic.

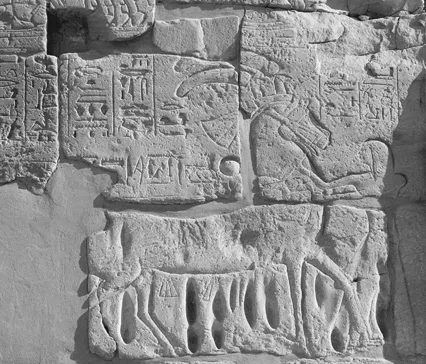

Fig. 13. Crown prince Sethy-Merenptah A on a block from his father’s battle reliefs at Karnak. His name and titulary have been largely erased.

Fig. 14. Khaemwaset D as depicted in his father’s battle reliefs at Karnak.

One possibility is that they all actually represent crown prince Sethy-Merenptah, with the first element of his name for some reason omitted. The other is that the prince was indeed a son of Merenptah whose uraeus was added as a result of some aspect of the family intrigues that came to the surface at Merenptah’s death. We will return to this in the following chapters. A prince Ramessu-Merenptah might also have been a son of Merenptah—unless he was actually Merenptah himself before his accession.

Little is known of the events of the first years of Merenptah’s reign, apart from some inspections of temples in Years 2 and 3.21 However, in Year 5 a coalition of Libyans and the so-called Sea Peoples from the northeast Mediterranean22 made an incursion into northwest Egypt before being defeated at “Perire,” a place of imprecise location, but certainly in the southern part of the western Delta.23 These events were recorded in the king’s Great Karnak Inscription and associated reliefs in the Cour de la Cachette in the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak (fig. 15).24

Fig. 15. The Cour de la Cachette at Karnak, showing the eastern wall that bears Merenptah’s account of his Libyan campaign.

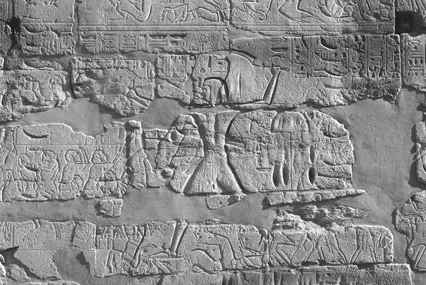

Further military activity was directed to the east and was commemorated in a set of reliefs on the outer wall of the Cour de la Cachette (figs. 16–17). These were carved over part of an unfinished version of the Qadesh reliefs of Rameses II, which were masked in plaster.

Fig. 16. The Ashkelon Wall at Karnak, bearing the victory reliefs of Merenptah and the Hittite treaty of Rameses II (fig. 11). Merenptah’s images were carved over what was originally the right-hand part of an unfinished depiction of Rameses II’s Battle of Qadesh, continued from the left-hand section on the adjacent outer face of the south wall of the Hypostyle Hall.

Fig. 17. Detail of Merenptah from the Ashkelon Wall; note the erased and surcharged cartouches.

As Rameses II had himself carved a fresh set of battle reliefs over another part of this palimpsest Qadesh tableau (on the outside wall of the Hypostyle Hall), for many years the Cour de la Cachette-wall reliefs were misattributed to Rameses II as well. However, the latest work on them, by Peter Brand, has confirmed Frank Yurco’s earlier assessment that they were certainly carved for Merenptah, whose cartouches were subsequently erased.25 The campaigning shown in these reliefs seems to illustrate the coda to the victory stelae that were erected in Merenptah’s memorial temple (figs. 18–19)26 and in the southeast corner of the Karnak Cour de la Cachette.27 In the stelae, the polities of Canaan, Ashkelon, Gezer, Yenoam, and Israel are poetically described as having been defeated by Merenptah, and it appears that at least some of them were depicted in the reliefs.28 The mention of Israel has long made Merenptah a figure of particular interest to students of the ...