This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

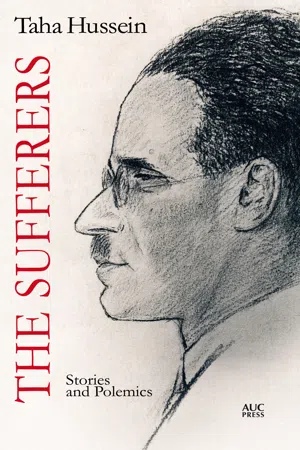

Taha Hussein (1889-1973), blind from early childhood, rose from humble beginnings to pursue a distinguished career in Egyptian public life, but he was most influential through his voluminous, varied, and controversial writings. The stories in The Sufferers were first published in the periodical al-Katib al-Masri in 1946, but were banned by the government when collected in book form in 1947. The collection was finally published in Lebanon, and was only published in Egypt after the 1952 Revolution.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Sufferers by Taha Hussein, Mona El-Zayyat in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Littérature générale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LittératureSubtopic

Littérature généraleSaleh

“When you hear the shaykh raising his voice with the last Allahu akbar, tell me. If you do that, then you are truly my son.”

The boy smiled at his mother, who had been speaking to him while stroking his cheek, and said, “And if I don’t, then whose son would I be?”

The boy’s mother was taken aback for a moment, and her sons and daughters around her laughed. But she slapped the boy’s cheek tenderly and said, “You have a cheeky tongue and are given to argument.” Then, slipping a piece of sugar in his hand, she repeated, “When you hear the shaykh raising his voice with the last Allahu akbar, tell me, and if you do so, you will get another like it before you sleep.”

The boy bit the sugar eagerly, saying, “Now that makes sense!” Then he darted out, followed by the laughter of his mother and of her sons and daughters around her.

The house was in a bustle that evening as guests of influence and importance in the province had arrived. They had not come empty-handed bringing with them many rare objects as presents.

The mistress of the house was always keen to be hospitable to guests and so was waiting for the last Allahu akbar with which the shaykh would raise his voice, ending his sunset prayers.

The various courses had been prepared and were waiting to be served as soon as the guests were done with their prayers. The tharid, the first of these courses, was almost ready. The bread had been cut into little pieces and placed in a large dish and the broth had been prepared, as well as the rice. The garlic had also been diced. However, the final touches to this dish should only be done at the last moment to avoid the bread becoming soggy with the broth, and to prevent the aroma of the garlic and the vinegar it has been browned in from escaping. The rice should also not be allowed to grow cold, or the melted ghee that has been poured over it will coagulate.

For all these reasons the boy had to listen to the prayers of the shaykh until he raised his voice with the last Allahu akbar, when he should rush to his mother and tell her, and she, in turn, would rush to these mixtures of bread, broth, garlic, vinegar, and rice and combine them in the large dish awaiting them. Once dinner had begun with this dish, it would be followed by the other dishes in their own time, for there is no harm in delay.

Yet the boy told his mother nothing, because he heard nothing. He was distracted from both the first and the last Allahu akbar by a serious matter. The shaykh and his guests finished their prayers. They sat down to talk and wait for the dinner that would be brought to them. The shaykh was restless as he waited. He was not accustomed to such slackness when entertaining guests. More than once he thought of clapping his hands to inform the household members that they were wailing. But he was embarrassed to do so, disliking the idea that he would be suspected of needing to warn the household and that it, in turn, would be suspected of inattention and carelessness. So he continued conversing with his guests in a raised voice. One of his daughters, passing behind the door, heard this loud conversation and rushed to her mother telling her what the son had neglected to tell her. An instant later the guests were at their table, eating noisily.

The boy had meant well. He had taken up his observation post in a nook of the courtyard where several pieces of iron, which he considered to be his treasure, lay. He would often sit alone there, gathering and separating the iron, and pounding the pieces against one another. This was the pastime in which he indulged, sometimes alone, sometimes with his little sister.

He sat in his little nook with his iron and he decided to play with it as soon as he had finished eating the sugar, while lending an ear to the shaykh and his guests, listening to their prayers and waiting for the moment when the shaykh’s voice would rise with the last Allahu akbar. He would then hurriedly slip to his mother to tell her, before returning to his play.

But he had hardly settled down in his nook and started to gnaw on the sugar, when he felt a hand on his shoulder. He looked up and saw his classmate, Saleh, leaning toward him, touching his shoulder with one nand and holding in the other a bunch of wild flowers, which he offered with a smile.

He looked at Saleh and was horrified by his tattered clothes. His chest showed more than it should. His shirt was split at the shoulders, revealing them unbecomingly. His garment was threadbare and filthy—it bared more of the boy’s body than it covered. It seemed to be a collection of tatters sewn together and hung on a weak and feeble body to conceal whatever they could, so that it would not be said that he was going naked.

The boy raised his head and saw Saleh’s face, pale and full of misery, but with a smile full of sadness and hope.

He saw two restless eyes Hitting around, down to the iron bars scattered on the ground, up to the piece of sugar in the boy’s hand, and further up, toward the grape vines hanging on the wall and over the posts supporting them.

Saleh’s hand was still extended to his companion with the artless, coarse bouquet of wild flowers. He said, “I didn’t want to go home without coming and giving youthese buds that haven’t bloomed yet. Take them and put them in a container with some water and wait until morning. They will open up and become beautiful, sweetsmelling flowers!”

The boy said nothing. He took the flowers and gave Saleh what remained of the piece of sugar in his hand, beckoning him to sit down and join him in play.

Saleh took the sugar and contemplated it for a long time. He brought it close to his mouth, and took it away again. Then he gave it a last, short look and quickly stuffed it in his cheek and waited for it to melt slowly, prolonging his pleasure. Then he sat down and began to turn over the pieces of iron with his friend.

The silence between them did not last long. They began to talk about the kuttab (the school where they learned the Quran), their classmates, the field, and the villages. All this made the boy forget about the shaykh’s prayers, the guests, and the news he should have taken to his mother. Only the voice of his sister calling him to dinner from behind the door startled him.

The shaykh and his friends had finished their dinner, as well as the last prayer and what invocations followed it. The night-time coffee had been served. The mistress of the house, assembling her sons and daughters to dinner, had noticed our naughty friend was missing and had sent his sister to search for him.

When the boy heard his sister calling him, he hesitated in answering her as he did not know how to deal with his friend. But Saleh’s low, sad voice was saying, “Answer. You are being called to dinner.”

The boy said to Saleh, “And have you had your dinner?” Saleh answered, “I will have dinner when I go home,” and he stood up heavily and turned to leave. Had he been able to, he would have stayed. But he went.

The boy went back to his mother, carrying the flowers. When she saw him she reprimanded him for forgetting her order. But she asked him who had brought him the flowers.With a quiver in his voice, the boy said, “Saleh, the son of Hajj ‘Ali brought them to me.”

“And you gave him nothing?” his mother asked.

“I gave him what I had left of the piece of sugar,” said the boy.

His mother replied, “And what do you think he can do with the piece of sugar? Do you think he can ward off his hunger with it? Did you not ask him to stay for dinner?” Confused, the boy said, “I started to, but didn’t dare.” His mother said, “Follow him quickly and bring him back to have dinner with you.”

The boy darted out like an arrow, barely passing through the door before calling his friend. He did not need to run any further, nor did he need to repeat his call. For Saleh was standing in front of the house, leaning against the wall, staring in front of him. He had one leg forward, the other backward, wanting to go, and wanting to stay. When he heard his friend calling him, he answered meekly, “Here I am, what do you want?”

“I want you to stay to dinner,” said the boy.

Saleh said nothing but turned to his friend and quietly followed him, his head downcast, as a dog follows his master when summoned.

When the boy closed the door behind him he found that one of his sisters had placed a stool in his nook. On it was a round tray with all the dishes that had been offered the guests. She had chosen not to share the dinner with the family and had insisted on serving the two companions.

When they had finished eating, Saleh left with a full stomach, and the contented boy returned to his mother.

Stroking his head, she told him, “If a classmate of yours visits you at dinner time, you mustn’t let him leave without inviting him to share your meal.” Then, after a short pause, she said, “Do you know that Saleh only brought you these flowers to be invited to dinner?”

“I didn’t know,” answered the boy. His mother said, “He saw the guests when they came, and he saw the presents they brought, and realized there would be plenty to eat in the house this evening. He wanted to get some of it, and so used these flowers as a pretext to come to the house.”

“If only you had seen his clothes and how his chest and his back and his shoulders showed through them!” exclaimed the boy.

His mother said, “When you come out of the kuttab tomorrow, persuade him to come with you. I have some of your clothes to give him.”

Then she turned her attention to her other sons and daughters, talking to them about the guests and the dinner. She reprimanded one daughter for having forgotten to stir the rice when she dropped it into the boiling water, almost turning it into a sticky, useless dough. For rice should not coalesce, nor should its grains be allowed to stick together. Each grain should be separate. She praised the other daughter for being careful with the faluzag. She had not prepared it as a liquid that runs off the spoon as a soup would, nor had she made it so solid that it would need to be cut into pieces. She had not neglected to stir it, and so had avoided the disagreeable lumps that make it unpalatable and difficult to eat. It had been smooth and pleasant to the tongue. Hardly had it entered the mouth than it was summoned by the throat. It was also light and tasty.

While she was talking to her daughters about these things, by which she taught them the art of cooking, and while her listening sons laughed heartily, the boy interrupted her and asked her why Saleh had not had dinner at his home.

“Didn’t I tell you that he knew we had lots of delicious food and that he wanted to get some of it?” asked his mother.

The boy said, “But I see guests calling at our neighbors and I know they will have many delicacies, yet I don’t go to their children and try to get some of what they have.”“Because you don’t need to, since you’re not deprived,” she said.

“So Saleh is deprived, then?”

His brothers and sisters were getting annoyed at his persistence, but his mother was amused, and said, “Because your father has a source of livelihood, while Saleh’s father has been reduced to poverty.”

“Why?” asked the boy.

“You are a chatterbox,” answered his mother. Then she turned to the eldest of her daughters and said, “Take him to bed. It’s late and time for him to sleep.”

Next morning, the boy woke up and went to his kuttab as he did five days a week.

It might occur to the reader to ask me about this boy. What is his name? Where does he come from? Who is his family? Who may he be? If these questions have occurred to the reader, I would answer him—as Diderot used to answer his readers when he imagined they were questioning him about aspects of his novels—that he is taxing both himself and me with questions, the answers to which might be useful in rendering a novel symmetrical and well built, its parts in harmony and enjoying the proper sequence of events as required by the old critics. But I am not trying to construct a novel and thus do not have to make it obey the literary laws outlined by the great critics.

For a novel to be perfect, the place and time must be specified, and the identity must be revealed of the persons to whom events are happening or who cause these events and of those who are exposed to misfortunes or who contrive them.

I am not writing a novel that obeys artistic principles, and, had I been, I would not have taken it upon myself to submit it to these principles. For I do not believe in them, nor do I attend to them, nor do I admit that the critics— whoever they may be—are entitled to set down for me any rules or laws whatsoever. Nor do I acccpt from the reader,however high-placed he may be, any interference between me and whatever words I set forth. They are but words that occur to me and that I dictate, then publish. Whoever wishes to read them may do so and whoever grows weary of reading them may turn away. Whoever wishes to approve of them may do so with thanks, and whoever wishes to be scornful of them may also do so, with thanks.

The important thing is that words should occur to me and that I should dictate and publish them and that the reader should find that which allows him to practice his freedom of will, which is capable of either enticing him to read or impeding him from doing so.

It is also important that the reader should feel that he has a selective taste by which he can recognize art and by which he can accept or reject it; this is no small matter. I do not want the reader to think that I am lording over him, or that I am being unfair to him. For I am the last person to be domineering and the least likely to be unjust.

I have a most intense love and respect for the reader. But I do not like him to dominate me or to be unjust to me either. Nor do I want to force my taste on him, as I would not like him to force his on me. Freedom should be the sound basis for the relationship between the reader and myself, when I write and when he reads. If I respond to these questions and thus reveal the home town of this boy and his environment, and if I make known his family, then this narrative will be longer than I like.

There is not only one boy in this narrative, there are two: one of them is Saleh, who makes of the wild flowers a means of obtaining his dinner, and the other is that boy at whose home Saleh finds that dinner. To be fair, I admit tha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Modern Arabic Writing

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Translator’s Introduction

- Introduction

- Saleh

- Qasim

- Khadija

- Al-Mu‘tazala

- A Comrade

- Safaa

- Danger

- Social Awareness

- The Burden of Wealth

- Generosity

- Ailing Egypt