![]()

GROUPS, COMMUNITIES AND

CATCHMENTS

![]()

10

Managing floodplains in northern

Australia

Tony Searle

The Mary River floodplain in the Northern Territory is part of a large network of over 10 000 km2 of coastal freshwater wetlands. The geomorphology of the Mary River floodplain system has resulted in the formation of a vast and comparatively long-lasting shallow wetland. This special habitat results in a biodiverse and ecologically valuable environment. The Mary River region supports tourism, recreational fishing and pastoral industries; the extended retention of fresh water throughout the driest part of the year is of particular value to grazing in the region.

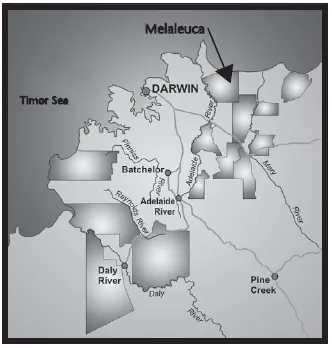

‘Melaleuca Station’ is a 300 km2 property (30 000 ha) situated 200 km east of Darwin owned and managed by the Paspaley Pearls Company. Sixty per cent of the station is made up of seasonally inundated floodplain which is influenced by both fresh and saltwater river systems. Much of the remaining country is tropical savannah woodland. The average annual rainfall is 1800 mm, usually spread over a four-month summer period.

MIMOSA PIGRA

Mimosa pigra is regarded as one of the worst weeds in Australia and was declared a weed of national significance by the Australian government in 1999 (Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council 2006). Mimosa aggressively outcompetes native plant species, rapidly forming impenetrable and unpalatable thickets, and can spread quickly and colonise wetland areas. Mimosa can block access to stock watering points, hamper mustering and destroy productive native floodplain grasslands. It affects production, cultural and conservation values of wetlands – pastoralists are among the worst affected. Fifteen catchments in the Northern Territory are currently affected by mimosa, the greatest impact being felt on the landscape and ecology of the Mary, Daly, Finniss, Reynolds and Adelaide River systems.

Figure 10.1: The location of stations involved in co-ordinated weed management. Melaleuca is the property to the west of the Mary River (top right)

As mimosa has now spread extensively across multiple catchments, land tenures and properties, it is imperative that landowners work together to co-ordinate a systematic management approach across catchments. Melaleuca Station has been a major player in a three-year project which has resulted in 17 pastoral properties in the Mary, Daly, Finniss, Reynolds and Adelaide River catchments joining forces to create a united front against mimosa. The area involved exceeds 10 000 km2.

Melaleuca Station was originally part of Point Stuart Station, used predominantly for buffalo grazing. In 1980 the mimosa infestation was small, but by 1995 one-third of the property (more than 10 000 ha) was infested. The property’s carrying capacity was limited to 200 head of cattle as all the productive country had been rendered useless by the aggressive weed. The mimosa had rapidly formed dense and impenetrable monospecific stands. Its rapid expansion could be attributed to buffalo numbers and the inaction of the previous owner.

THE MIMOSA PIGRA CONTROL PROGRAM

In order to regain the valuable floodplain country, Melaleuca Station developed a Mimosa pigra control program. The plan aims to clear the mimosa strategically and systematically, and thereby regain productive land for both cattle production and environmental purposes. In this type of program, the achievement of management objectives will only become evident in the long term and this has to be acknowledged from the outset. Patience is required after initial clearing of mimosa, and continuing maintenance, monitoring and management is imperative. Once a control program is initiated, ‘commitment’ is the key word. Reinfestation, if untreated, is only one wet season away.

CONTROL METHOD

- The mimosa infestation is tackled one plot at a time (plots are 500–1000 ha). The plot to be cleared is selected one year in advance. In the early wet season (December) the plot boundary is sprayed to create a 100 m perimeter of dead mimosa (Figures 10.2, a, b and c).

- In the late dry season (October) of the following year the plot perimeter is chained and sprayed again (chaining is a common method of clearing land by dragging a heavy chain between two tractors, to uproot plants). The woody debris is then stick-raked up against the green mimosa plants within the plot (Figure 10.2d).

- The plot is then burnt, using an accelerant. Using a helicopter, the middle of the plot is set alight first then the boundaries are lit to draw the fire inward. The effectiveness of the fire depends greatly on the climatic conditions. Ideal conditions involve winds in excess of 30 km/h, a temperature of 35°C or greater and relative humidity less than 25%. If the fire burns very hot, there will be little regrowth as the fire will have destroyed the majority of the seeds. A cool burn will result in more regrowth from fire-induced seed germination.

- Flooding usually commences in the early wet season (December–February) and inundates the new seedlings, killing the majority.

- In mid-late dry season (July–August) the following year, when the floodplain is dry again, the entire plot is chained.

- In the following December, the young mimosa plants are sprayed. Large areas are systematically sprayed using helicopters, using a meticulous ‘run-by-run’ approach. It is important that no plants are missed.

- At this stage (early in the wet season on the first storms) some revegetation of floodplain grasses can begin, but it is not the optimum time. Often grasses cannot adequately establish as the floodplains become inundated.

- Once the country is opened up to sunlight, natural revegetation can begin with the establishment of sedges, reeds, annuals and perennials.

- After the floodwaters have receded and the plain dries out, the large amount of woody material remaining on the clean plot is stick-raked into piles and burnt.

- The next year (almost two years after the initial fire) assisted revegetation commences. This involves the dispersal of seeds or planting of runners as floodwaters are receding (July–August). Adequate groundcover will limit the re-establishment of mimosa. It is important that grasses have the opportunity to establish, particularly in floodplain channels, before the next wet season.

- The establishment of diverse and palatable vegetation results in the re-establishment of faunal populations. Some species, including feral pigs and geese, can negatively affect floodplain water quality which, in turn, affects production.

- Once native and introduced pasture species have been established (two to three years), light grazing can take place to encourage further spread of the grasses.

- Plots are then maintained by spraying with herbicides. Spraying is predominantly carried out by helicopters until mimosa plants are sparse and spot-spraying can be used.

- Eventually, a conscious economic decision may be made to leave some areas of mimosa and treat only every two years. This is contrary to past practices which aimed to kill all mimosa plants in the control program areas.

- Full production is normally achieved by year 5, with continuing maintenance.

Figure 10.2:Mimosa pigra control on Melaleuca Station using a combination of mechanical and chemical methods. From top left, clockwise: foliage; thickets after spraying; after burning and raking

INTEGRATED AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT

The federal National Landcare Program (NLP) has contributed more than $400 000 to this project. The pastoral industry spends $1.2 million each year at a ratio of 10:1 private:public funding on pastoral lands, with a further $1.7 million spent on all other lands. The cost of controlling mimosa varies with density, soil type and location (floodplain or timbered country costs $20–500 per ha). Success of the project to date has relied on the development of integrated property management plans for each of the properties involved. The plans, developed with the assistance of the Northern Territory Department of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts, aim to first control mimosa high in the catchments in order to limit reinfestation in valuable floodplain areas. Restorative work then continues to reclaim crucial grazing areas. This has involved partnership between pastoralists, Aboriginal land managers, local government, the Northern Land Council, the Indigenous Land Corporation and the Northern Territory Cattlemen’s Association. The result is a more cost-effective and efficient weed control strategy which will increase biodiversity protection and productive capacity.

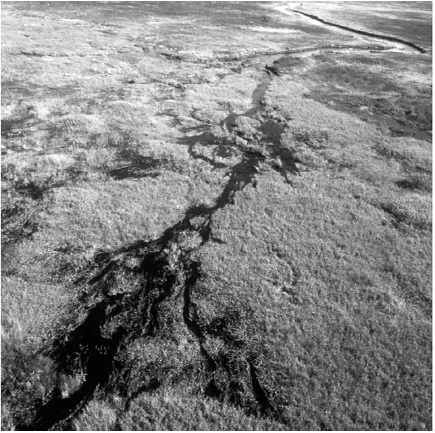

Figure 10.3: Floodplain on Melaleuca Station showing rehabilitated area (top right)

The project recognises that a holistic approach is necessary for effective natural resource management. Weed management cannot be viewed in isolation from other land management practices which influence productivity and profitability on the floodplain country. Landowners must manage feral animals, erosion and fire on their properties – pastures which are compromised or stressed by these factors are more susceptible to weed invasion.

Mimosa control on Melaleuca Station complements the use of multiple biological control agents, particularly in the remaining areas of high infestation. Twelve potentially damaging insect species and two fungal pathogens are currently being trialled as control methods by the Department of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts. The addition of biological control vectors, if successful, will prove invaluable in supporting existing regrowth control measures and controlling satellite infestations.

SALTWATER INTRUSION

The Mary River system does not have a large single outflow to the sea. It has been suggested that prior to 1940 the Mary had practically no outlet, as a series of low sandy ridges (cheniers) formed a physical barrier along the coast. The cheniers, in conjunction with mangrove fringes, effectively separated the freshwater wetlands and coastal waters (Woodroffe et al. 1990). Saltwater intrusion into the wetlands began in the 1940s and accelerated in the 1980s, progressively inundating approximately 240 km2 of the wetland system. The problem is believed to have resulted from crocodile hunters and buffalo shooters explosively breaching the natural rock bars to allow boats to transport goods in and product out of the floodplains. Buffalos have also been implicated in the destruction of ancient chenier ridges at the coast.

The Mary River floodplains are now significantly affected by saline intrusion. This kills salt-sensitive vegetation and replaces it with saline mudflat habitat, which in turn is gradually colonised by a salt-tolerant mangrove ecosystem. The dramatically changed environment cannot support cattle grazing or native floodplain fauna.

Works to mitigate saline intrusions, including the construction of a network of earthen barrages, have been applied in the Mary River system since the 1980s. The floodplain is notably low-lying, with most of the 50 km wide plain lower than the chenier ridges. Preventing further saltwater intrusion is therefore challenging from both engineering and labour perspectives.

Satellite monitoring indicates that these mitigation actions have been effective in many areas but they need constant monitoring and maintenance. Riverbank erosion and propeller damage to earthen barrages continue to risk the passage of salt water into these freshwater systems.

PRODUCTION

Melaleuca Staion’s main enterprise is backgrounding (growing livestock to a weight suitable for live export) cattle stock for the live export trade from Darwin to south-east Asia. The floodplain country is the most productive on the property, consisting mainly of heavy black self-mulching soil at or below sea level.

In the past these plains were severely degraded by the large numbers of feral buffalo that grazed the area. The subdivision of the original Point Stuart Station improved management of feral animals and the national Brucellosis and Tuberculosis Eradication Campaign (BTEC) assisted in reducing buffalo numbers. The country is now more productive and ecologically intact. However, the continuing management of fire, weeds, saltwater intrusion and feral pigs is vital in maintaining these environmental and productive gains on a sustainable basis.

The cattle production system revolves around the wet/dry seasons with the carrying capacity great...