eBook - ePub

The Complete Field Guide to Stick and Leaf Insects of Australia

This is a test

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Complete Field Guide to Stick and Leaf Insects of Australia

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Australia has a rich diversity of phasmids – otherwise known as stick and leaf insects. Most of them are endemic, few have been studied and new species continue to be found. Stick insects are, by far, Australia's longest insects – some of them reach up to 300 mm in body length, or more than half a metre if you include their outstretched legs. Many stick insects are very colourful, and some have quite elaborate, defensive behaviour. Increasingly they are being kept as pets.

This is the first book on Australian phasmids for nearly 200 years and covers all known stick and leaf insects. It includes photographs of all species, notes on their ecology and biology as well as identification keys suitable for novices or professionals.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Complete Field Guide to Stick and Leaf Insects of Australia by Paul D Brock,Jack W Hasenpusch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

At present, we recognise 101 species of stick insect and three species of leaf insect in Australia, but there are likely to be more species awaiting discovery. Worldwide, there are about 3000 species of phasmids, mainly from the tropics. These scrub-dwelling or tree-inhabiting, nocturnal insects have fascinated generations of people. Their ability to remain motionless, resembling sticks or leaves, as a primary mechanism of defence can make them difficult to find. At times, some species are plentiful and become much more conspicuous by resting on doors, windows and walls of houses, and on cars at popular nature reserves.

Stick insects are by far the longest insects in the world, several species measuring close to, or over, half a metre when their outstretched legs are included. Stick and leaf insects are easily recognised, being generally thin and stick-like, sometimes with leaf-like legs, but usually not. On the other hand, true leaf insects have a broad, leaf-like, almost flat body. Some stick insect species, including 70 of the Australian species, have wings, although these may be very small and quite useless for flight. Many species are completely wingless.

Phasmids belong to the insect order Phasmida (or Phasmatodea), generally accepted to be closely related to Orthoptera (grasshoppers, katydids, and crickets) and are allied to cockroaches (Blattodea) and praying mantids (Mantodea). Phasmids are sometimes confused with slender mantid species, but the latter have forelegs designed to catch and eat live prey, whereas phasmids eat vegetation.

Stick insects are plant feeders – this Goliath Stick-insect, Eurycnema goliath, is feeding on a eucalyptus leaf.

The Australian stick and leaf insect fauna (although less than four per cent of the global richness) includes many of the most striking phasmid species found anywhere in the world. Some of them have only recently been described, such as Parapodacanthus hasenpuschorum, described in 2003, and the longest Australian insect, Ctenomorpha gargantua, described in 2006. In several cases, older literature records have assisted in locating species only known from specimens caught in the 1800s. It is fortunate these insects still survive, as widespread clearing of habitat in the past has changed the Australian landscape and adversely affected the numbers of insects in general. It is pleasing that farmers and other individuals and organisations, supported by government policies, are keen on habitat conservation.

Some species are females only, reproducing by parthenogenesis – usually their eggs hatch only into females. The ‘Amazing Facts’ section opposite gives an indication why rearers and collectors become fascinated by phasmids. They exhibit such a wide range of behaviour and are often one of the most popular exhibits in zoos.

Anyone who has searched for phasmids in the wild knows they can be elusive, best found at night. It is amazing to see huge insects stand out amongst the vegetation. Sometimes they are very common, but search the same localities in the daytime and one would be very fortunate to find any at all as they are so well hidden.

One of the many forms of phasmid defensive behaviour – the startle display. This is a female Strong Stick-insect, Anchiale briareus.

This Robinson’s Stick-insect, Candovia robinsoni, is not just blowing bubbles. The secretion from its mouth is a common form of defence in many phasmids.

AMAZING AUSTRALIAN PHASMID FACTS

- Females of the Gargantuan Stick-insect, Ctenomorpha gargantua, are reported to reach an overall length of 615 mm, including outstretched legs.

- During peaks in population, pest species are capable of defoliating forests.

- The Titan Stick-insect, Acrophylla titan, holds the record for number of eggs laid (over 2050) by any phasmid

- Phasmid eggs are much sought after by ants. The eggs of many phasmid species have a knob which ants feed on after transporting them underground. The eggs are then protected from parasites and many predators.

- The Lord Howe Island Stick-insect, Dryococelus australis, is literally hanging onto life on the tiny volcanic island, Ball’s Pyramid. Thought to be extinct, it was rediscovered in 2001.

- The true broad-bodied leaf insects are rare, but do exist, although hardly anything is known about them.

- Australian stick insects have made several film appearances; Macleay’s Spectre, Extatosoma tiaratum, appears regularly on television programmes, including ‘I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here!’ in the UK, where contestants have had to eat these insects, or put their hands into cages containing specimens.

A female Macleay’s Spectre, Extatosoma tiaratum, star of horror films. Its mouthparts and antennal segments can be seen clearly.

The life cycle and behaviour of phasmids fascinates rearers of these insects. They are easy to keep in culture and are particularly popular with schoolchildren, as they are easy to handle.

Many phasmids have a range of defence behaviour, suddenly opening brightly coloured wings, kicking out with spiny hind legs, producing fluid from their mouthparts, spraying an irritating chemical, or simply playing dead.

External anatomy

Most phasmids are relatively large, conspicuous insects. Males are often smaller and slenderer than females. Because the variation between the sexes (known as sexual dimorphism) is sometimes extreme, it may be difficult to indentify a male and female as belonging to the same species unless they are mating. With practice, identification will become more straightforward and identification of commoner species should be fairly easy, although variations in size, colour or body form may be expected from time to time, and can be confusing.

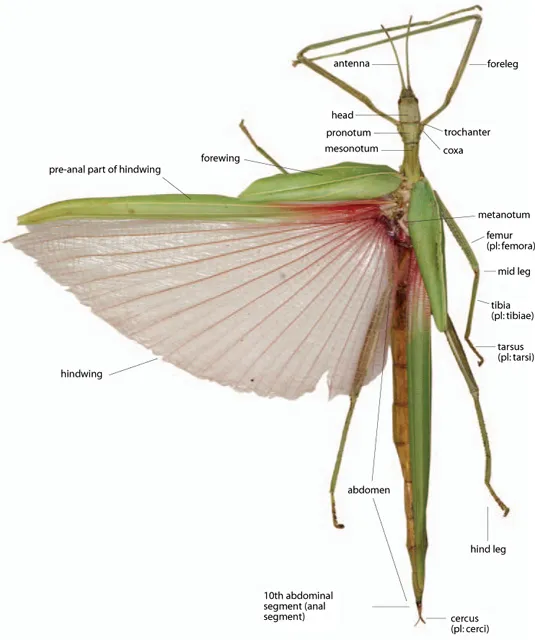

Wingless Denhama and Hyrtacus species as well as the smaller, winged species may be particularly difficult to identify, often requiring an experienced phasmid specialist to examine them. Details of the basic structure of phasmids are given below.

Head

The head of a phasmid is oval to rectangular in shape, sometimes armed with spines, horns or protuberances. The head is made up of numerous plates (or sclerites) fused together to form a solid capsule that carries the paired antennae, the eyes and the mouthparts.

The slender antennae are sometimes short, but more often long, consisting of between eight and 80 (or more) segments. The antennae of the female are shorter than those of the male. They are covered by sensory hairs, important for helping the insect detect its surroundings. The length of the antennae provides a useful first stage in identifying the species, although nymphal antennae in many species are often shorter than those of the adult.

The pair of compound eyes varies in size, and many species have relatively small eyes. Made of many separate units, the compound eyes can perceive movement, unlike smaller ocelli (where present), which detect the presence of light. Three ocelli only are present in a minority of winged species, usually only males.

A stick insect spends much time eating and its mouthparts consist of the labrum (upper lips), a pair of mandibles (jaws) suitable for chewing leaves, and a pair of maxillae (secondary jaws), each of which bears a five-segmented sensory palp (the maxillary palp), and a labium (lower lip), which has a pair of three-segmented labial palps. The palps help the stick insect in touching and tasting its food plants.

Thorax

The elongate thorax consists of three segments, which bear both the wings and the legs: the shortest segment, the prothorax, carries the forelegs; the second, and usually longest segment, the mesothorax, carries the mid legs and forewings (if present), and the third segment, the metathorax, carries the hind legs and hind wings (if present). The metathorax is usually shorter than the mesothorax and may be fused with the first abdominal segment (the median segment). The upper surfaces of the three segments are known as the pronotum, the mesonotum and the metanotum respectively.

The key parts of a stick insect.

The thorax is smooth in some species, or may include a variable number of granules, tubercles (small knoblike or rounded protuberances) and/or spines. The thorax is often very long and stick-like, but is particularly broadened in the true leaf insects.

The legs are often long and slender and may be smooth, spiny or lobed, often with ridges and/or grooves along their length. The first segment is a small coxa, and the second segment (trochanter) is also much reduced. The long third segment, or femur, is sometimes stout. The base of each fore femur usually has an inner depression, to accommodate the head when the legs are extended forwards when at rest. The tibiae are slender, often longer than the femora, possibly with a short pair of spines at the tip, like th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Habitat and ecology

- 3. Collecting, preserving, photographing and rearing

- 4. Guide to species

- Appendix 1: Keys to genera and species

- Appendix 2: Classification of phasmids

- Appendix 3: Checklist of Australian phasmids

- Glossary

- References

- More about phasmids

- Index of common names

- Index of valid scientific names