![]()

1

Environment and justice: defining the field

Anna Lukasiewicz

Justice and the environment – what are we actually talking about?

When we talk about the intersection of environment and justice research, we refer to diverse but inter-related bodies of study that deal with: environmental management, including wildlife management as is prevalent in the US (Andrews 1999); community-based natural resource management, popular in Africa and Australia (Jones and Murphree 2004; Curtis and Lefroy 2010; Curtis et al. 2014; Lockwood et al. 2010), and climate change, which is a global concern (Ikeme 2003; Thomas and Twyman 2005). All of these bodies of literature refer to interaction of humans with natural systems or resources such as soil, water, biodiversity and the industries that are dependent on them, such as agriculture, forestry, mining, fisheries and tourism. In other words, we consider research that specifically examines these socio-ecological interactions through the prism of justice (Schlosberg 2007) at all scales. Such research examines the interactions between human groups as they endeavour to arrive at ‘just’ decisions in relation to the environment and allocation and use of natural resources.

At this point the reader may simply shrug their shoulder and exclaim ‘but that is simply environmental justice – nothing new’. The problem with simply calling this field environmental justice is that the term is both all-encompassing and limiting, depending on which body of literature one draws on. Environmental justice research traditionally looked at distribution of environmental costs or negatives, such as pollution, inequitable access to environmental resources and relative lack of access to environmental decision making among vulnerable social groups (Agyeman et al. 2003) but in some disciplines it has since expanded to include a multitude of other concerns (Schlosberg 2013), although this expansion is not recognised in all disciplines (Reed and George 2011).

Our ‘intersection point’ between justice and environment thus definitely includes the distributional and procedural aspects of environmental justice, but it also includes research in social justice, which looks at the allocation of goods and benefits within a society, focusing on distributive, procedural and relational fairness, often from the viewpoint of marginalised or disadvantaged stakeholders (Syme and Nancarrow 2001; Whiteman 2009). Social justice sometimes considers human–environmental interactions (Foster et al. 2010), but the majority of its research remains firmly anthropocentric. Both environmental and social justice often view the environment as a passive background against which justice is played out. Recently, a trend has emerged to pick an environmental theme and to concentrate justice research around it: for example, water justice (Perreault 2014; Zwarteveen and Boelens 2014); climate justice (Posner and Weisbach 2010); or food justice (Gottlieb and Joshi 2013; Wittman 2009). In contrast, ecological justice identifies the environment as a subject of justice – a stakeholder to whom justice is owed (Driscoll and Starik 2004; Opotow and Clayton 1994; Starik 1995; White 2008). Other fields that contribute to our ‘intersection point’ include: environmental law (Le Bouthillier et al. 2012); ecological economics (Costanza 1989); environmental philosophy (Mathews 2014); and aspects of political theory and research into human rights (Gearty 2010; Hancock 2003).

Justice discussed in this book is inclusive of the environmental, social and ecological justice concerns mentioned above and involves, but is not limited to: research around justice concerns of governance (access to, participation and influence in decision making – procedural fairness); access to the resource (distributional fairness); public benefit and the costs and benefits of resource use on different stakeholders (alleviating unequal burdens); economic and socio-political power asymmetries between different stakeholder groups; the impacts of resource use on non-human life and ecosystems (inclusion of the environment as a stakeholder); and consideration of long-term effects (benefits and burdens across generations – inter-generational equity) and across and between species (inter-species equity). It is also worth noting here that most justice research starts by identifying and researching injustice.

A further point needs to be made about words commonly substituted for ‘justice’. There is some confusion about whether words, such as fairness and equity, are indicative of nuanced differences, or whether they essentially mean the same thing. Again, the answer depends on the disciplinary context. Some disciplines, such as philosophy, differentiate between justice and fairness, while others, in the social sciences, tend to use the two terms interchangeably (see Finkel et al. 2001 for a discussion of the two terms). The term equity is commonly used in economics and is sometimes used interchangeably with fairness across the social sciences. We suggest that recent advancements in this field warrant a more theoretically sound basis for research that deconstructs or unravels components of justice.

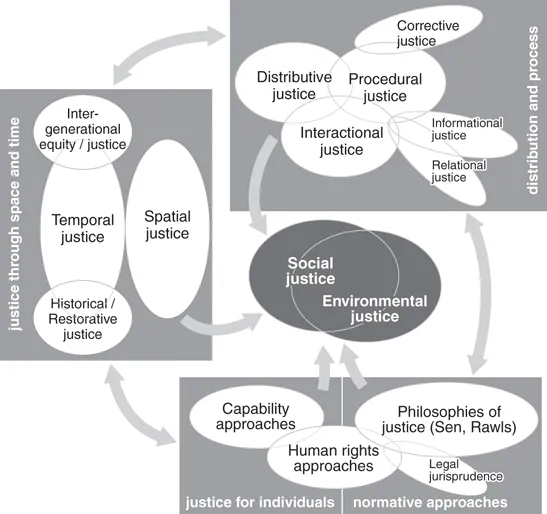

Given the disciplinary diversity described above, the reader will find individual chapters referring to different (yet somewhat complementary) conceptualisations of justice. Figure 1.1 is a map of the different justice typologies presented in this book. It shows four groupings of justice types: based on scale (temporal and spatial justice); aspects of the decision-making process (distributive, procedural and interactional justice); and justice philosophes and human rights. The environmental and social justice grouping sits in the middle of the diagram because it encompass aspects of the other three. Here we must comment on the normative and descriptive nature of the different justice types. The justice types grounded in philosophy and law (normative philosophies and human rights approaches) are largely normative (i.e. they deal with how things ought to be). However, the types of justice arising out of psychology, geography and history (spatial and temporal justice, distributive, procedural and interactional justice) tend to be more descriptive, concerned with analysing what is, rather than what ought to be. These divisions are largely nominal, however, because all these types are inter-connected. For instance, a researcher may take spatial or temporal justice as a focus and through that lens deal with distributive and procedural justice issues in order to compare what they see with Sen’s Idea of Justice. Social and environmental justice can thus be either normative or descriptive, depending on the individual researcher’s disciplinary background and how they choose to mix and match different justice types.

Figure 1.1. Justice typologies.

Chapters 2, 15 and 18 refer broadly to environmental justice (in its more inclusive definition), while Chapter 3 talks about social justice, within the environmental context. Chapters 8, 11, 14 and 17 all use the common three-dimensional conceptualisation of justice (distributive, procedural and interactional), which is based on the social psychology understanding of justice. While this concept is commonly used, it is not the only way of understanding justice. Chapter 7 also uses these three dimensions of justice but adds temporal and spatial, as well as informational, justice (which others might categorise as a mixture of procedural and interactional justice). Chapter 9 uses a somewhat different conceptualisation: historical justice (also sometimes called restorative justice); while Chapter 6 focuses on relational justice (a mixture of procedural and interactional justice). Chapter 16 examines different conceptualisations of justice, including the philosophies of Rawls (2009) and Sen (2009), as well as corrective and political justices. Other chapters use disciplinary understandings of justice: philosophy (Chapter 10), law (Chapter 12) and economics (Chapter 13 and 15). We leave it up to the reader to decide on the most appropriate name for this research field, be it environmental justice, social justice or a combination of any of the above. The last thing we want is to create additional terminology to add to the existing array of terms.

Resources and the environment

Now that we have considered what justice means, we need to describe what justice is applied to, which ranges from the prosaic natural resources through to the natural world, the environment and more holistic and spiritual nature. How we conceptualise the environment is partly determined by the type of justice we wish to apply to it. That the environment can be both a subject and object of justice has already been mentioned above. However, the environment can be purely an ecological construct of complex coupled ecosystems, or a more spiritual conceptualisation of nature as a divine entity. It can be a background to questions of human justice or a key life support system that is itself owed justice.

The term resource is also a relative construct. A resource is valuable to its user group but may have negative or neutral value to non-users. Furthermore, the status of a resource can vary over time or from place to place. The specific aspects of the environment discussed in this book range from general resources such as air, water and soil or focus on individual species or concepts. The latter include notions such as access to green spaces and sustainable living. Although this book aimed to cover a range of environmental and natural resource concerns, some are more prominent. The focus on natural resource management, particularly sharing among different stakeholder groups, is representative of the type of research that is commonly done in Australia. The chosen themes represent the most topical and conflict-ridden natural resources: water, mining, energy and forestry. We acknowledge that some areas of research, such as the religious dimension, are missing.

The very term natural resource management puts humans in an active role of making decisions about the environment, which is relegated to a set of resources (Crawhall 2015). One could simply use the term environmental management but that has similar conceptual limitations. Regardless of the term, we aim to be inclusive of the different conceptualisations of the environment and include research that places the environment as an object and a subject of justice. As for justice above, we have chosen not to construct new terminology and leave it up to individual authors (and the reader) to choose language appropriate to their applications.

Who does this kind of research in Australia?

Given the wide variety of contexts covered in this book, all authors feel as though their chapter contributes to the intersection point of justice and environment set out above. However, given the wide boundaries, what then are the commonalities that would enable ongoing identification with the group? Surprisingly, despite the disparate research approaches and disciplinary diversity, we have found a lot of commonalities in researcher attitudes and motiv...