![]()

1

THE CARNIVOROUS MARSUPIALS

Can you imagine a mammal that weighs as little as a penny yet leaps five times its own height to take down prey far larger than itself? If not, can you visualise a rapacious killer that dispatches each victim with a deft bite to the neck before ripping its head off?

How about flesh-loving devils that relentlessly pursue victims to exhaustion then simply tear them to pieces? The hunting pack squabbles over the carcass in a screaming feast all night long, making enough racket to wake the dead. By morning, not a trace of the victim remains. Even its bones are ground to powder by a formidable predator sporting the most powerful jaws for its size of any living mammal.

What of maniacal male mammals that unceremoniously grab females by the neck to mate in frenzied sex sessions lasting up to 14 hours straight? The males invariably mate themselves to death, poisoned by their own raging hormones. Females are nymphs, and their clutch of young will have several fathers. With greedy mouth and grasping arms, their babies race each other to the mother’s pouch. Once there, they attach to the first available nipple, suckling its life-giving milk. With all teats taken, late arrivals to the pouch simply wither and die.

What about prehistoric forms that include apex predator equivalents of lions, tigers, bears, wolves and even sabre-toothed, flesh-eating kangaroos?

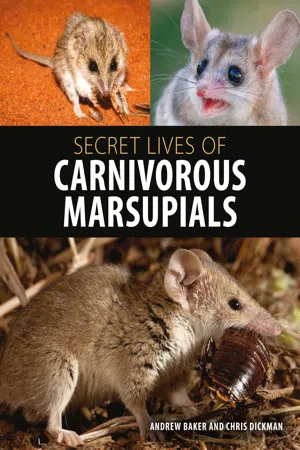

Collectively, these animals are known as carnivorous marsupials. They include ~136 living species, inhabiting remote parts of Australia, the Americas and New Guinea. These unique creatures are secretive, rarely encountered and little understood.

Many of Earth’s species, among them carnivorous marsupials, have succumbed to the pressures imposed by human sprawl – sent to extinction in the last few hundred years. Many more carnivorous marsupials are under serious threat of extermination, amid Earth’s sixth and first human-caused, mass extinction.

How can we save the survivors that remain?

More practically perhaps, as a society, why would we wish to save them?

First, humanity must appreciate these unique and secretive animals and decide they need to be saved – this requires knowledge and understanding. Without such knowledge, we can, and will do, little or nothing collectively to intervene. Recent decades are testament to this. To ultimately save and conserve our precious carnivorous marsupials, then, we must first and foremost get to know them. That is the aim of this book.

What are marsupials?

Marsupials form one of three groups that together comprise the living mammals. There are more than 5500 living species of mammals; over 330 of these are marsupials, five are monotremes, while the dominant remainder comprises placental mammals. Most female mammals, including all placentals and marsupials, give birth to live young and then suckle them with nutritious milk, but female monotremes, which include the platypus and echidnas, lay eggs. After hatching, the young of these ancient mammals are fed on milk crudely oozed from skin glands on the mother’s belly. Despite these differences, all mammals are united by their ability to produce milk and also by their possession of fur. These traits distinguish them from other vertebrates (animals with backbones). Other modern groups of vertebrates include amphibians, reptiles, birds and fishes.

Fig. 1.1.The Endangered Black-tailed Dusky Antechinus (Antechinus arktos) is found only in the highest, wettest ancient Gondwanan rainforests of eastern Australia. Source: Gary Cranitch.

There are numerous differences between placental and marsupial mammals, especially relating to reproduction. Female placental mammals, including humans, nurture their young before birth with a placenta. Offspring come into the world fairly well developed. Marsupials, in contrast – including iconic species such as koala, kangaroos and wombats – are born at a very immature stage of development and look like pink jelly-beans. Although a simple placenta forms in all marsupial species, it nourishes the young for a relatively short part of their overall development; in some species, this may be just a few days. The tiny young crawl up to the mother’s ‘marsupium’ or pouch, attaching to nipples there. The marsupial pouch may be fully developed, as in kangaroos, or it may be simply a naked depression on the belly with some skin folds that only partially protect the young as they grow. The latter is the case in most carnivorous marsupials. In marsupials, most of the reproductive effort occurs during a prolonged suckling period. Male placentals have testicles behind/under the penis. Marsupial males have the opposite arrangement. Male placentals may have non-functioning nipples, while male marsupials typically have no nipples at all, although some at least have mammary cells as pouch young.

Fig. 1.2.The Silver-headed Antechinus (Antechinus argentus) (viewed from the underside) – one of Australia’s rarest mammals and likely endangered. This is ‘Polly-Jean’, a pit-tagged two-year-old mother with eight, 4-week-old young. Antechinuses have no discrete ‘pouch’, just a depression on the belly which cannot contain the rapidly growing offspring for long. By 6 weeks old, the young are simply too large for the mother to carry around. She leaves them in a nest of leaves while she forages, returning several times during the night to suckle the babies on her nutritious milk. Source: Andrew Baker.

What makes a marsupial ‘carnivorous’?

Animal dietary strategies have traditionally and simply been divided into three broad categories. Herbivores eat plants, carnivores eat meat and omnivores eat both. However, this classification is too vague to account for the complexity of all feeding strategies. Some animals switch diets at different parts of their life cycle or even between seasons. Others consume mostly flesh and incidentally eat plants when ingesting the guts of their herbivorous prey. Some animals have very specific diets. For example, there are those that consume solely fruit (frugivores) or nectar (nectarivores). Others, such as a few species of bats, eat only blood (sanguivores). There is overlap in many prey categories. For example, species preying mostly on insects are insectivorous, but broadly speaking they may be considered carnivorous because they kill and eat animal prey. Insects are animals too! What’s more, finding out an animal’s diet is not a trivial exercise, especially for solitary and secretive species that are difficult to find and observe under natural conditions. Such elusive animals must be caught, their scats (i.e. faeces or poo) collected and analysed under a microscope. The scattered hard fragments of pre-digested prey remains in faeces are not easily identified, even by experts. Sometimes, prey items such as soft-bodied worms and slugs cannot be seen in scats at all. In such cases, only an analysis of DNA (see following section) in the faeces may reveal the identity of prey items. In short, this means there is conjecture as to how best to categorise the diet of any animal. For our purposes, it is debatable how many marsupials may be considered carnivorous. In part, this is because not all species have been subjected to study. However, many species that have been well studied include variable amounts of fruit or other plant products in their diet. Here, we nominate as carnivorous those marsupials with diets that consist by majority (more than 50%) of vertebrate or invertebrate prey. Even so, some marsupials inevitably fall across the grey borders of ‘carnivory’ into other dietary categories, and we mention some of these at the end of the next chapter.

Fig. 1.3.Carnivorous marsupial diets vary, but most of the smaller species, such as this Common Planigale (Planigale maculata), eat a variety of invertebrates. Source: Steve Murphy.

Diversity: how many carnivorous marsupials are there?

Earth’s creatures are taxonomically positioned using a system invented by Carolus (Carl) Linnaeus in the 1700s to impose a classifying order on relationships. The structuring may be familiar: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus and species. These various groupings describe relationships between organisms and their evolutionary patterns are often represented in diagrams called ‘trees of life’. The kingdom is the most all-encompassing category and, for creatures, includes all animal life. Species, by contrast, can be viewed as very fine branches on the tree of life and represent collections of individuals that are similar in appearance, genetic structure and behaviour. Because of the extraordinary diversity of animals – living as well as extinct – these categories are themselves often sub-divided. For example, all mammals are grouped together within the phylum Chordata with the other vertebrate groups mentioned earlier, but are separated from them within their own class, Mammalia. Marsupials are then grouped below the level of class but above the level of order in their own intermediate category, the ‘infraclass’ Marsupialia. Some scientists have proposed alternatives to this arrangement, but all agree that marsupials form a large and diverse group within the class Mammalia.

Some debate also surrounds the formal definition of species. We return to this issue in more detail in Chapter 4, but provide a brief background here as a primer. For most creatures, a good rule of thumb is that members of the same species can be recognised if they are at least potentially able to breed with each other. We emphasise the word ‘potentially’ here for good reason. Species sometimes have broken and discontinuous distributions due to loss of habitat, changes in climate or other reasons, and these isolated populations may then begin to diverge from each other as they adapt progressively to local conditions. Animals in these isolates could potentially interbreed if they were able to come together, and thus conform to our definition of species, but the isolated populations may be given their own ‘subspecies’ names if they are different enough to warrant it. How much difference is enough? This remains a vexed question, but increasingly it is being answered by detailed molecular studies of an organism’s DNA. DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), the double-helix molecule that carries the building blocks of life, differs between all living things and, most usefully for biologists, allows us to identify different organisms. It is not usually necessary to describe the entire genetic material of animal species to understand their relationships with each other; comparisons of selected regions of DNA can suffice. In essence, if these selected regions of DNA are compared and show little or no difference between populations, the populations can be considered to belong to the same species. Assuming differences in DNA have gradually accrued over time, increasing differences in the DNA are suggestive of subspecies, and then of species, genera, or even more distant relationships on the basis that they are increasingly less likely to be interbreeding. Here, we note where DNA analyses have been used to identify species and to describe relationships between groups of species, and use the concept of subspecies mostly to describe geographically different populations of the same species.

Genus and species names, which are often of Greek or Latin derivation, are italicised, and together form the scientific name of a species. The combination of genus and species (e.g. Antechinus arktos) is unique for every organism on Earth. Unlike common names, which can sometimes be the same for different species, scientific names cannot be confused. To maintain readability we use species’ common names throughout the text, but also provide the scientific name at the first mention in each chapter. If we are discussing several species in the same genus, we also use the scientific shorthand of abbreviating the genus name to just its first letter. Thus, if Antechinus arktos is mentioned and we then refer to another antechinus species, it will be introduced as A. followed by the specific name (e.g. A. adustus, A. stuartii). We also follow the convention of capitalising the first letters of species’ common names, such as Rusty Antechinus (A. adustus) and Brown Antechinus (A. stuartii). This ensures clarity in referring to the species in question rather than adjectives to describe their colour or behaviour.

Fig. 1.4.An excellent example of living carnivorous marsupial diversity. The extraordinary, Endangered Numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) is a survivor of an ancient group. DNA and morphological analyses suggest that Numbat ancestors last shared common ancestry with other marsupials ~30–40 million years ago. Source: Jiri Lochman.

The living carnivorous marsupials total ~136 species within 32 genera and six families. Almost half (45%) of these occur only in Australia – some 61 species in 15 genera, three families and two orders. But almost as many carnivorous marsupials (43%) reside only in the Americas, totalling 58 species in 13 genera, three families and three orders. These are found mostly in South America, but also the southern and central reaches of North America, with four species (in as many genera) found in the Central American isthmus and Mexico. Eleven per cent of the world’s carnivorous marsupials are found only in New Guinea, including 15 species in six genera, one family and one order. Just two species (1%) of carnivorous marsupial species are shared between northern Australia and New Guinea. These two countries, plus New Zealand, comprise the majority, by landmass, of Australasia. Yet New Zealand has no native marsupials – and just two living native land mammals, both bats (derived from Australia). The Americas share no living marsupials whatsoever with Australasia. Thus, most living carnivorous marsupials are ‘endemic’ to their landmass – found there and nowhere else. And some species, as we shall discover, have very limited distributions indeed.

So the reader can better appreciate their diversity, we briefly introduce each of the carnivorous marsupial genera in Chapter 2, providing a snapshot of their history of discovery, taxonomy, biology (breeding, behaviour, diet) and conservation. These are themes that we return to in more detail later in the book. We also provide an appendix listing all species with their common and scientific names and family relationships. This will be a handy reference to consult when carnivorous marsupials are named in later chapters.

![]()

2

GUIDE TO CARNIVOROUS MARSUPIALS

In the accounts of genera in this chapter, we refer to:

1.‘Size’, which equates to the average adult body length, including the head, body and tail, and range of body weights (in brackets).

2.The ‘IUCN (International Union for Conservat...