![]()

1

Introduction

An increasing number of Australians want to be assured that the food and fibre being produced on this continent has been grown and harvested in an ecologically sustainable way. This will increasingly be a major challenge for society as human populations continue to expand, rates of resource consumption increase, and some kinds of resources become increasingly difficult to grow, find or extract. The challenge is:

• How can we maintain or even increase food production without undermining the productive capability of farms and without significantly eroding biodiversity?

Ecologically sustainable farming means producing food (including meat) while at the same time maintaining the quality of soils, preserving (and even expanding) patches of native vegetation, and conserving the array of species that are integral to key ecological processes such as pollination, seed dispersal, natural pest control and the decomposition of wastes (e.g. the carcases of dead animals).

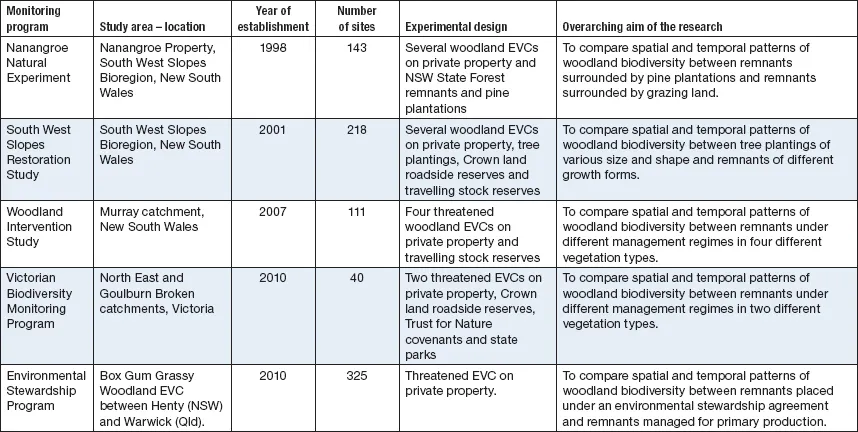

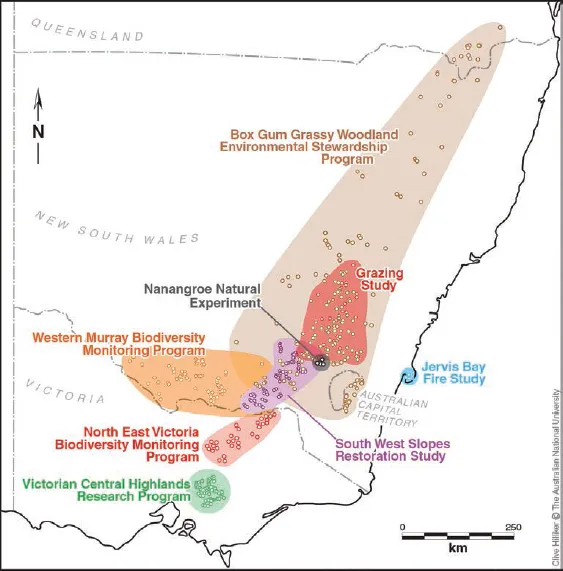

The challenge of developing ecologically sustainable farming management practices has been a major objective of research by The Australian National University (ANU) in agricultural south-eastern Australia since the late 1990s. Our work has grown over the past 17 years to encompass sites and farms from central Victoria, through NSW to south-eastern Queensland. In all, we now work on over 847 field sites that are located on over 300 farms (Table 1.1; Fig. 1.1). Indeed, our research – part of which entails many repeated visits to permanently established field sites – is arguably one of the largest scaled terrestrial monitoring programs in the world. Visiting so many sites, farmed in different ways and in different regions, has provided a large number of the insights that feature throughout this book. On this basis, we outline ways that different groups of animals and plants might be conserved on farms, while at the same time ensuring that those farms are viable businesses.

Table 1.1.Long-term biodiversity monitoring programs being conducted by the Fenner School of Environment and Society at the ANU in the temperate woodlands of south-eastern Australia and which form the basis of work summarised in this book.

The information reported in this book is based on surveys conducted across various ecological vegetation communities (EVCs) in each study area. Monitoring program

Fig. 1.1.Map of the location of field studies and site locations conducted by the ANU throughout the agricultural areas of eastern Australia.

The underlying philosophy of our applied research work and the scientific process

Our underlying research philosophy is to provide high-quality scientific information to landholders, regional land managers and other interested people to help them implement best practice farm conservation and farm management. That is, we gather the scientific evidence to guide making decisions such as where and when to do plantings or which remnants of native vegetation are the best ones to protect.

Positive conservation management is often billed as a negative for farm economics. Not so. On this farm near Wagga, the Chalkers have worked hard to improve the quality of the waterbodies by strategic fencing and controlled stock access points around dams and creeks. This has led to improved water quality for stock and assisted in maintaining water availability during prolonged dry periods. At the same time, waterbody management has significantly improved bird biodiversity on the farm, with a dramatic increase in bird species richness (particularly of bird species of conservation concern) over the past decade. Photo by Mason Crane.

There are several ways in which robust scientific evidence can be gathered. The approach used by our team at the ANU is relatively simple to write down, but painstaking and time-consuming to do. We outline this approach below as we believe that it is important for readers to appreciate how the science is conducted and how our conclusions are reached:

1 A land manager or member of our scientific team identifies a significant problem or set of issues for which there is currently no definitive scientific answer.

2 A field study is rigorously designed to address the problem. This is typically in a collaboration between scientists, professional statisticians and land managers (including farmers). This part of the work usually entails carefully defining the questions to be posed, the statistical design that can be used to implement a study to answer those questions, and the methods employed to collect the data in the field.

3 A small pilot study may be conducted to determine if the experimental design proposed to implement a study is actually possible to do on the ground.

4 The results of the pilot study are examined and the study (if viable) is then fully established.

5 Following initial establishment, our field studies may run for several years and sometimes decades.

6 At various intervals during long-term data collection, a sixth (and critical) stage is that information from the field is subjected to detailed statistical analysis. This is typically done through a partnership between an expert statistical scientist and one or more ecologists.

7 The results of statistical analyses are written up and then assessed by colleagues within the Fenner School at the ANU. Scientific articles demand precise writing to emphasise what discoveries have been made. It is also essential to make it clear what scientific and statistical methods have been used so that other scientists could replicate the work if they so desired.

8 When the scientific article is of sufficient quality and all the details of the analysis and writing are finalised following comments from colleagues, it is submitted to a national or international scientific journal to be considered for publication. Such articles typically undergo thorough critique from anonymous referees, with requests to revise the article to improve its quality. This eighth stage is a very tough one in which a scientific paper is often rejected by one or more journals. The article must then be further revised and improved before it is submitted to another journal. It may take submission to four or five journals before a scientific article is finally accepted – a process that may take 2–3 years if the target is a high-quality international journal. This long and arduous process of science publishing requires considerable patience, a thick skin (to deal with repeated criticism and rejection), and a massive dose of persistence. Many members of the public are unaware of just how tough (but also rigorous) the scientific publishing exercise can be.

9 Widely communicate the scientific findings to a broad audience. When a scientific article is published, it is then available for other scientists, as well as any member of the public or management organizations, to read. However, few people even know that most of scientific journals even exist, let alone read the highly technical articles they contain. We therefore work hard to produce books (such as this one), posters, glossy brochures, calendars and DVDs. We also present our findings to natural resource managers in workshops, to landholders at field days, and give lectures to school groups. These activities are designed to ensure that our new scientific findings are communicated and accessible to a wide audience beyond scientists and academics.

Repeated and careful measurements of biodiversity made over many years provide the essential, high-quality empirical data needed to determine how species are changing, and why they are changing. Many members of the research team at the ANU have been working on the same sets of farms in Victoria, NSW and south-eastern Queensland for well over a decade. Photos by Damian Michael, Dan Florance, Mason Crane, Dave Blair and Thea O’Loughlin.

Of course, there are many different approaches to creating quality evidence-based science beyond those underpinned by the collection of field-based empirical data. These include genetic analyses of samples collected in the field, systematic reviews of the literature, and simulation modelling (such as predicting the viability of populations of animals or plants). We have employed all of these methods in our 17+ years of research in Australian agricultural landscapes. But our general approach is always the same. That is, rigorously gather scientific information, subject those data to the best possible statistical analyses, write up the results at the highest possible standard, and widely communicate key findings.

The concept of ‘scale’

Our many studies have been conducted at different spatial scales – from a single bird nest or large hollow tree through to entire regions or even multiple regions. As an example, we have worked on the success of individual nests of birds, the use of individual trees (such as paddock trees) by marsupial gliding possums, on the importance of particular patches (e.g. a planting or a woodland remnant) for birds, reptiles and mammals, and on the value of entire farms and landscapes for supporting populations of particular species and assemblages of animals. These different studies completed at different spatial scales provide different insights about animal responses to agricultural environments and what management actions might be most effective at particular scales. Indeed, exciting discoveries can be made when our datasets are simultaneously analysed at several scales.1 These multi-scaled studies tell us that actions at one scale (such as the farm level) can have profound effects on biodiversity at other scales, such as the likelihood a given patch will be occupied by a particular species of bird (see Chapter 2). Such investigations also indicate that actions at a given scale, such as the decision to establish a planting or fence a woodland remnant, can (and does) make a positive difference to the environment at several scales.

Improving outcomes for biodiversity on farms requires a strong working partnership between landholders and researchers. Farmers implement particular kinds of management interventions on farms and researchers design rigorous scientific studies to determine the effectiveness of these interventions for improving outcomes for wildlife on farms. Scientists then communicate their results to farmers and suggest ways in which management might continue to be improved (e.g. by changing the width and shape of plantings). Updated management actions then continue to be subject to research and monitoring, underscoring the value of farmers and scientists working together to improve the integration of wildlife conservation and agricultural production. Photo by Mason Crane.

Another kind of scale is time. The scientific jargon sometimes used is ‘temporal scale’. Environments are never static and Australia, in particular, is famous for climatic variability: all landholders are critically aware of the major changes in the environment between very wet and extremely dry years. It is therefore very important to track and quantify changes in the environment and in populations of plants and animals over time. Documenting the effects of time is crucial for other practical reasons. Long-term work is needed to answer vital questions such as: How soon after planting will an area be colonised by birds or possums? Will an area naturally regenerate if it is fenced off? Yet, precious few ecological studies in Australia are conducted for more than a handful of years at best. We have worked extremely hard to break that unfortunate tradition and many of the insights we summarise in this book are based on many years of continuous detailed field research.

Sometimes long-term studies lead to new perspectives that appear to be inconsistent with previous work – including our own previous studies. For example, our early work suggested that plantings rarely supported any species of possum...