![]()

Part I: Principles for conservation

The multifaceted nature of conservation biology

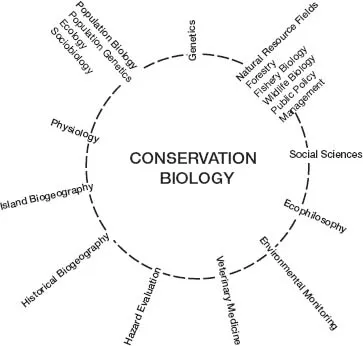

Conservation biology is the applied science concerned with the management of biological diversity (or bio-diversity). Although biological information is needed to inform decision-making about conservation and natural resource management (Clark, 2002), conservation biology is more than just ecology – much of ecology has no conservation implications. Rather, conservation biology draws on methods and problem-solving skills from many disciplines, including animal behaviour, chemistry, ecology, education, genetics, geography, mathematical demography, medicine, philosophy, policy, political science, sociology and statistics (see Ludwig et al., 2001; Aguirre et al., 2002). In fact, conservation biology could be thought of as a meta-discipline (Brewer, 2001; see Begg and Leung, 2000; Pullin and Knight, 2001; Fazey et al., 2005a).

Soulé’s conservation biology principles

Two decades ago, Soulé (1985) outlined the broad principles that underpin a multidisciplinary approach to modern conservation biology (Figure B1). In essence, the principles state that biodiversity and potential for evolutionary development are intrinsically valuable, and that conservation biology seeks to reduce rates of species extinction and biodiversity loss. Soulé’s (1985) principles influence much of the discussion in this text.

The tension between ‘pure’ and ‘applied’ conservation biology

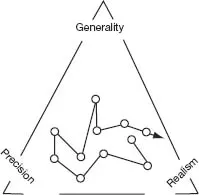

Conservation biology goes beyond the traditional boundaries of the life and physical sciences to include such things as advocacy (New, 2000; Ludwig et al., 2001). It shares this attribute with epidemiology, in which practitioners believe there is an obligation to influence public policy and decision-making, for the sake of public good. There can be tension between the results of ‘pure’ conservation research and the ‘real-world’, practical applications of conservation biology. This tension is embodied in the trade-offs between generality, precision and realism illustrated in Figure B2. Whelan et al. (2002) describe this as the ‘fire triangle’, with reference to fire ecology research. The fire triangle is based on earlier ecological work by Harper (1982) and Hairston (1989), and is equally relevant to applied conservation biology.

Figure B1. Soulé’s (1985) vision of conservation biology as a multidisciplinary field. Some contributing areas are arguably no longer appropriate, such as island biogeography (see Chapter 10). (Redrawn from Soulé, 1985.)

The philosophy in Figure B2 is important because, although there are some broad generalities in conservation biology, application details are nearly always specific to a species, a group of species, a site, a landscape or a region. Such complexity is the reality of conservation biology. Krebs (1999) highlighted the disappointment of numerous ecologists who have found that their supposed ‘generalities’ did not apply to other systems.

Figure B2. The conservation biology triangle, adapted from fire research (see Whelan et al., 2002) and syntheses of ecological work by Harper (1982) and Hairston (1989).

At the outset of a book on conservation biology, it is important to establish the boundaries of the discipline and to set the framework within which problems are identified and solved. Part I of this book explores, in general terms, why we wish to conserve biodiversity (Chapter 1), what it is we wish to conserve (Chapters 2 and 3), and some of the mechanisms by which conservation can be achieved (Chapter 4).

Box B1

Real world conservation biology: dealing with ‘wicked environmental problems’

At the end of almost all sections of this book there are important caveats about the uncritical application of concepts, methods, equations and general conservation tools. Whether the topic is simple rules for reserve design, ratio estimation for species diversity, indicator taxa, species-loss equations, or habitat suitability indices, we outline the reasons why these approaches are often not ‘magic bullets’ and why their uncritical application could actually deliver poor biodiversity conservation outcomes. If anything, these sentiments highlight the challenges posed by practical conservation biology, and emphasise that the science of conservation biology is inexact, young, and still evolving. Much of what is in this book will be found to be wrong in 20 years; but making mistakes and learning how to better manage ecosystems and conserve biodiversity is a natural part of the scientific process and the evolution of conservation biology as a meta-discipline (Redford and Taber, 2000; Berger et al., 2004).

An additional issue associated with the multidisciplinary nature of conservation biology is that the field often deals with what have been termed ‘wicked environmental problems’. Ludwig et al. (2001) noted that such problems are truly complex in that they have: (1) no definitive formulation, (2) no stopping rules to determine when a problem has been appropriately addressed, (3) multiple legitimate human perspectives, (4) radical uncertainty, and (5) no test for a solution – in part because the solution will be unique in each case and it will not represent the final resolution of a problem. The outcome will often depend on how the problem is framed and by whom (Maddox, 2000). Lindenmayer and Franklin (2002) quoted Bunnell et al. (2003) as stating that ‘forest management is not rocket science – it is much harder’. This sentiment is perhaps even more true of conservation biology.

![]()

Chapter 1

Why conserve?

This chapter provides a framework for explaining how different attitudes to environmental management develop and coexist. It explores the different values people hold for biodiversity and the natural environment, such as utilitarian, consumptive, productive use, service, cultural, spiritual, experiential, existence, aesthetic, recreational, and tourist values. The chapter also explores the ethical basis for conservation. The topics discussed in this chapter are central to effective conservation practices because species and communities can be viewed either as objects used to serve human welfare, or as entities possessing value per se.

1.0 Introduction

Conservation biology attempts to conserve the diversity of living things (often termed biological diversity or biodiversity). There are many definitions of biodiversity (Bunnell, 1998; see Box 2.1 in Chapter 2). For the purposes of this book we define it as encompassing genes, individuals, demes, populations, metapopulations, species, communities, ecosystems, and the interactions between these entities.

This definition stresses both the numbers of entities (genes, species, etc.) and the differences within and between those entities (see Gaston and Spicer, 1998). It is similar to the definition of biodiversity proposed by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNCED, 1992):

the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic systems and the ecological complexes of which they are a part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems.

Most definitions of biodiversity in the literature consider genetic variation within species, the number of species and their relative abundances, variation in the composition of communities at the level of species and at other taxonomic levels, and the diversity of ecosystems and the processes that drive them (Harper and Hawksworth, 1995; Bunnell, 1998). Further discussion of the concept of biodiversity and its definition can be found in Chapter 2.

Objectives of conservation

The objectives of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (1992, cited in CCST, 1994) include:

the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilisation of genetic resources.

Conservation is defined by the World Conservation Strategy (IUCN, 1980) as:

The management of human use of the biosphere so that it may yield the greatest sustainable benefit to present generations while maintaining its potential to meet the needs and as...