This is a test

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Urban Nation: Australia's Planning Heritage provides the first national survey of the historical impact of urban planning and design on the Australian landscape. This ambitious account looks at every state and territory from the earliest days of European settlement to the present day. It identifies and documents hundreds of places - parks, public spaces, redeveloped precincts, neighbourhoods, suburbs up to whole towns - that contribute to the distinctive character of urban and suburban Australia. It sets these significant planned landscapes within the broader context of both international design trends and Australian efforts at nation and city building.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Urban Nation by Robert Freestone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Urban Planning & Landscaping

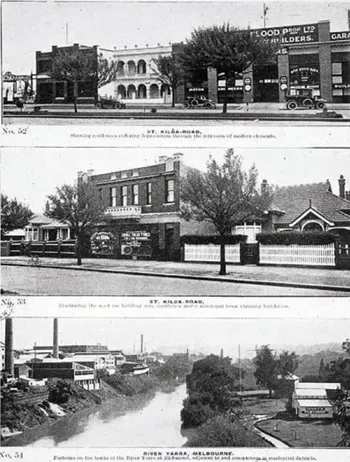

previous page: The archetypal planned urban landscape: An aerial view of Parliament House looking towards Canberra city centre in Australia’s national capital (2006).

© NCA

CHAPTER 1

A NATIONAL NARRATIVE

The scope of urban planning in the early twenty-first century is vast when compared to the far more restricted science of township layout at the beginnings of European settlement of Australia. This chapter provides a summary overview of the development of urban planning in Australia from the late eighteenth century to the present day, focusing on the evolution of general philosophies, the emergence of institutions, major events, and contribution of individuals. The emphasis is on the metropolitan areas which today house the vast bulk of the Australian urban population.

The treatment in this first chapter is basically chronological and sectionalised into phases, subjectively determined. An initial appreciation of the development of planning theory and practice in Australia might recognise four extended periods:

- Early history focused on the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries, covering the establishment of the colonial capitals and spread of settlement, largely through the proliferation of gridiron towns. This defines the period prior to the foundation of the nation and emergence of a genuine national perspective and institutions.

- 1901–1945 represents the arrival of modern planning thought, encompassing the first initiatives in planning legislation, administrative reforms, planned communities, establishment of a planned national capital, and the development of the state capitals as cities of metropolitan significance.

- Post-war planning covering the institutionalisation of planning at local state and more cyclically federal levels, marked also by the formation of a national planning institute, metropolitan planning strategies, regional development initiatives, and competing notions of both good planning and the good city.

- New Millennium planning from the late twentieth century marks the most recent era during which new administrative and legislative structures have evolved to address a complexity of contemporary concerns, with oftentimes conflicting issues of sustainability and economic development.

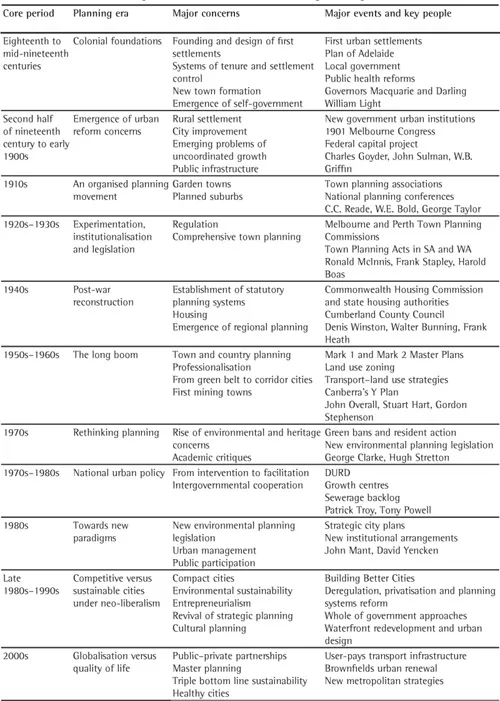

The sectionalisation adopted in this chapter develops this sequence by elaborating a finer grain of chronological-thematic phases (Table 1.1), drawing from previous research.1 In general terms, the Australian experience, while distinctive in detail, has parallels with overseas narratives, especially in Great Britain and the United States. This broader international backdrop is taken up more explicitly in the next chapter with reference to design influences, but more extensive treatments of the development of planning globally are provided elsewhere.2

Table 1.1 Basic chronological framework of Australian planning

Source: Adapted and developed from Hamnett and Freestone eds. 2000.

COLONIAL FOUNDATIONS

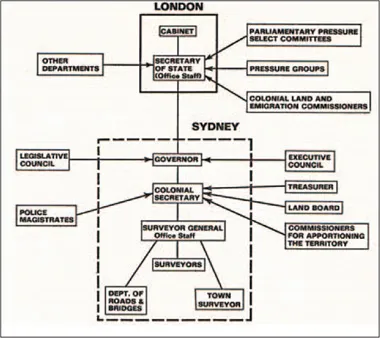

The earliest manifestation of planning in Australia was as ‘a process of conquest’.3 An authoritarian model of town planning predominated from the late eighteenth century through to the turn of the twentieth century. Two distinct sets of relationships are evident through this period.4 The first was through the period of administration by British-appointed governors, which lasted from the foundation of each colony (between 1788 and 1836) to the 1850s. The jurisdiction of the NSW Governor until 1851 included all of eastern Australia. The decision-making processes were hierarchical, with the British Government having a key plan approval role. The second phase dated from the 1850s when, following the Australian Colonies Act of 1850, each colony, except Western Australia, became separate and self-governing. The major theme throughout is a conception of planning limited to initial town layout.

This British Colonial Office/powerful British Governor phase commenced with the military-style order of the first encampments at Sydney Cove in 1788. Sydney is usually portrayed as a failure because Governor Arthur Phillip’s first plan was ignored and the Australian penchant for property speculation was established early. But a major achievement – eventually repeated in the other colonial capitals via different processes – was the reservation of government domains of parkland and botanic gardens. The tenure of Governor Lachlan Macquarie (1810–21) – who came from a military background in contrast to his predecessors, who were naval officers – saw the imposition of a more ordered sense of spatial organisation on the growth of Sydney, and in the initial expansion of the urban frontier through the colony.5 The ‘chief rule’ of town planning was ‘the control of population through the appropriate location of power’.6

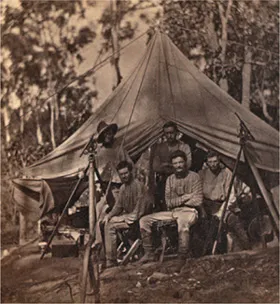

Surveyors in either the field or head office were the main town planners of the colonial era. They faced arduous conditions in the bush. The three greatest dangers were said to be black snakes, hostile Aboriginal people and bushrangers.7 Surveyors created the geometric foundations for capital cities and country centres, purposefully pegging out cities, towns and villages with the expansion of settlement. The time-honoured rectangular gridiron plan ruled. It matched the primitivism of early survey equipment, but was also widely accepted by those in power as the most economical, efficient and flexible form of physical plan-making. Within the grid, the aim was to give a frontage on the main streets to as many allotments as possible. But there was little realistic appreciation of long-term growth needs in the modern sense. The grid plan was sometimes displaced from alignment to the cardinal compass points (north–south–east–west) to make the best use of site and situation, but frequently the process was arbitrary with little sympathetic response to the nature of the site.

In 1829 Ralph Darling, Governor of New South Wales, with an eye to regulation and standardisation during a major expansion of urban settlement, codified the big square blocks and wide streets that characterise the typical Australian country town today. With the emphasis on uniformity, regularity, and rectangularity, urban settlement was to be limited and controlled. In the largest town, Sydney, the problem of ‘squaring the lands’ had already arisen where private habitation had taken place without reference to government controls.8 Once early restrictions on the location of settlement were breached, rural town formation could be a stand-off between spontaneous settlement and government decree, often with both surviving as twin towns.

The colonial bureaucratic decision-making structure for early land settlement and town surveys.

J.M. Powell and M. Williams, eds. Australian Space, Australian Time: Geographic Perspectives (1975). Courtesy of Dennis Jeans

The early progress of physical planning is captured in an historical lecture by the twentieth-century Australian planning pioneer Charles Reade to a London audience in 1925. He said that from the 1800s in Sydney, Hobart and other towns in Tasmania:

Numerous reserves for town sites, together with sites for public and ecclesiastic purposes, had been made. Leading towns had been equipped with squares, crescents and park areas, under the influence of British ideas and possibly early developments in the American colonies and other possessions. The laying down of important streets from 60 to 99 ft in width in place of earlier standards, based on 40 and 50 ft, had also been accomplished, but with only partial success.9

Town planning in the bush: Surveyors at work on the layout of Palmerston, later Darwin (1869).

SLSA: B 11603 – Government Surveying Party, Palmerston (Darwin), 1869

South Australia was a distinctive experiment in planned land settlement and the Adelaide plan of 1837 was the major achievement of colonial urban design, with parklands framing and encasing urban spaces sited with sensitivity to the natural landscape.10 Debate has raged as to who was responsible, but the template was set for ‘little Adelaides’ to be later stamped throughout South Australia, including what is now the Northern Territory. This orderly patchwork of ‘parkland towns’ neatly demarcated urban, suburban and parkland.

But town planning through to the late nineteenth century remained largely an exercise in surveying. The process was standardised into the marking out of allotments (usually of the same size), each fronting an area reserved as a street: ‘sites for major public buildings were nominated, but what private buyers might develop on the other parcels of land – shop, house or factory – was rarely considered by the surveyor, who in any case had no tools or powers with which to influence what might be built’.11

In a big continent with seemingly limitless land, suburbs emerged early, but once the basic cadastral survey had been completed, land subdivision and development was only weakly regulated. Formal town planning essentially ended with the physical outline of a very basic plan of development. Formation of roads, provision of basic infrastructure, building construction and landscaping tended to be discontinuous actions by independent actors responding to particular circumstances – often the representations of long-suffering communities.

RECOGNISING THE NEED FOR URBAN REFORM

Although notions of planning were rudimentary, complex structures of government were created to deal with everyday needs and pressures. Colonial governments soon recognised the advantage of moving some of the costs of building and rebuilding the cities to local government, once there seemed to be sufficient ratepayers to provide the revenue. The form of municipal government was strongly influenced by the British Municipal Corporations Act of 1835. Between 1842 and 1859 central city councils were established in every capital. Their key roles in the building of city centres extended across three stages: a primary phase of installing infrastructure like roads, bridges, squares, markets and council premises; a secondary phase of city improvement and regulation (health inspections, building controls, tree planting, maintaining parks and gardens, subsidising cultural activities); and a tertiary phase of ‘social engineering’, with comprehensive city planning and welfare schemes.12 The same evolution was experienced as suburban councils were created and proliferated.

Meanwhile, from the mid-nineteenth century, state governments also commenced creation of separate departments and semi-independent statutory boards independent of and overriding municipal government with important and specific city functions. Early examples were port authorities such as the Marine Board of Hobart (1857) and the Sydney Harbour Trust (1901).13 The role of specialist engineering-based infrastructure agencies (sewer, water, roads, power etc) from the late nineteenth century has been absolutely central to the urban development process. They have pursued their own sectoral and area plans, often relentlessly. Most advances in governance were reactionary and uncoordinated, a response to crisis. The potential for state–local tensions and for organisational complexity are still being wrestled with.

From the late nineteenth century, emerging problems of sanitation, subdivision, transport, water and sewerage provision, gas supply, housing, and harbour facilities in the big cities called forth the need for a larger scale of thinking and the need for some measure of coordination. This realisation helped lay the ground for more imaginative conceptions of town planning. Metropolitan dysfunction arose from what David Dunstan refers to as ‘a failure of political structures to adapt’. There were four key problematical institutional elements:

The need for zoning revealed by the mixture of conflicting land uses in Melbourne (1917).

SLSA Proceedings of the First Australian Town Planning and Housing Conference and Exhibition, Adelaide, 1917

- divided patterns of local authority which could not easily adapt to metropolitan functions

- the overriding authority of parliaments with their duty to colonies as a whole and lacking any structural affinity with the metropolis

- a layering of ad hoc problem-orientated authorities which tended to undermine local authority and created problems of coordination through their multiplicity and different allegiances

- the absence of auth...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 A National Narrative

- Chapter 2 Imagining Ideal Places

- Chapter 3 Founding the Capital Cities

- Chapter 4 A Nation of Planned Towns

- Chapter 5 Metropolitan Strategies

- Chapter 6 Suburban Dreams

- Chapter 7 Renewing Cities

- Chapter 8 Parks, Precincts and the Public Realm

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index