![]()

1

A walk on the beach

Ex Africa semper aliquid novi. (Out of Africa always something new.)

(Pliny the Elder)

There was a warm glow on both sea and sand that early Liberian morning when I went down to the beach to talk to my Lord.

The midsummer heat and humidity of the West African state were oppressive, but down at the beach where the waves washed in it was cooler, and both outer and inner man felt relief. Like the heavens and mountains, the ocean always announces Something Bigger. Man is not so mighty after all and certainly not ‘the measure of all things’.

The beach, that July 1961 morning, looked pristine. As if no mortal had ever set foot upon it. Beyond the sand, the dense tropical bush seemed just as it had been for centuries. I was to be the lone intruder on it all. And that was fine by me. Because all I wanted was some solitude and quiet to reflect and pray.

I was 24 years old, South African born and bred, and possessed of a crazy but persistent longing to take the news of Jesus Christ to every city in Africa. The whole of Africa.

This wasn’t just some fly-by-night notion but had crept up on me and been encouraged by many others. Our nation was needy. In so many countries, not least my own beloved South Africa, the brokenness was heart-wrenchingly evident. Who could see it and not long for a solution?

By the time I was walking on that Liberian beach, I was not alone in my endeavour and the fledgling organization African Enterprise (AE) was already under way. Our hearts were at peace and our minds settled, but we were signing up for a big job. What on earth would the evangelization of Africa through word and deed in partnership with the Church look like long-term?

That was what was preoccupying me on that beautiful Liberian beach.

The waves, with their to and fro and coming and going, seemed to beckon me forwards. And the beach in the early light seemed to call to me as if from God himself: ‘Come walk with me.’

The Lord, my Lord, felt very near. All I wanted to do was tell him he was mine and I was his – by purchase, by conquest and by self-surrender.

But more than that, I wanted to claim our partnership in this gospel endeavour.

I drew an enormous outline of Africa in the sand and wrote: ‘Claimed for Jesus Christ’.

I then asked the Lord for 50 years of ministry in Africa, ‘a year for every state presently on the African continent’.

Then, to clarify things further, I started to walk.

‘Lord Jesus, I am going to walk fifty paces and put fifty footprints in the sand. And I want each one to represent one year of ministry on the African continent. That’s what I’m asking you for.’

With deliberate steps I made my 50 footprints in the African sand, and made my earnest ask to the Lord of heaven and earth and sea and sky. Then, above the prints and parallel to them, I wrote again in huge letters: ‘Claimed for Jesus’.

My lone footprints were etched for an eternal moment on that deserted sand and I was satisfied. I was already sure of the Lord’s call on my life. Now I had made my own firm commitment to it and to the Lord, and I felt my prayer had been heard. We were in this together!

So how did it all begin?

Footprints in the African sand

![]()

Part 1

FORMATIVE YEARS

![]()

2

Roots

Where you will sit when you are old shows

where you stood in your youth.

(Yoruba proverb)

My mum and dad, in my naturally unbiased opinion, were the best of the best and, through them, I was the blessed of the blessed.

To them under God I owe the gift of life and the matchless privilege of being deeply loved, rascal though I was!

I had a wonderfully happy home and idyllic childhood in Maseru in old colonial Basutoland, which is now Lesotho. Dad, after being moved there by his Johannesburg company, was the senior mechanical and electrical engineer in charge of power, electric light and water. Mum for me was in charge of everything else.

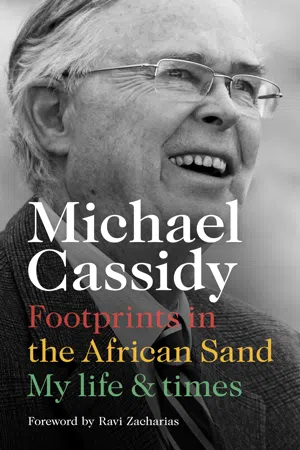

My parents – Dee and Charles Cassidy, Chaka’s Rock, Natal, North Coast, 1950

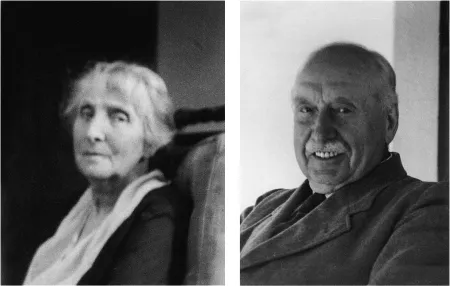

Charles’s parents – Catherine and Stewart Cassidy

Dad came of Irish stock, of ‘the very ancient Celtic family of Ma Cassidi or O’Cassidy’,1 from the village of Ballycassidy.

In our tribe there was an archdeacon, a doctor, a parish minister, a colonel and a musketry instructor, no doubt alongside their fair share of rogues and scallywags.

Anyway, my dad’s father, married to Catherine Startin in 1892, became a sailor and rose to become captain of a Union-Castle ocean liner and was regularly rounding the Cape of Good Hope before the opening of the twentieth century.

He died at sea, and his men placed a plaque in his memory in the Seaman’s Mission chapel in Cape Town. It is still there with its inscription: ‘Charles Stewart Cassidy. He was ever the Christian gentleman.’ I saw it long ago and photographed it with pride.

Mum’s lineage went back to the House of Craufurd, and included the renowned Scottish patriot, Sir William Wallace, who was popularized in the modern film Braveheart. So if you detect a touch of militancy in me now and then, or a tiny trace of aggression, blame it on my predecessors! The family, ever proliferating, and based mainly in Ayrshire, in due time had a castle all of their own. It was ‘ever so grand’ according to my sister Olave who has been to see it.

My mother’s mum, Ada Mary Craufurd, born in 1863, and nicknamed Molly, decided to follow her adventurous younger sister, Helen, out to South Africa where Helen had just married an engineer working on the proposed new railway line from Cape to Cairo.

Molly did her homework and finally tracked Helen and her husband Gordon Buchan down in the Northern Cape in a remote British garrison town called Mafeking, just as the Second Anglo-Boer War broke out between the British and the Afrikaners (Boers).

The Siege of Mafeking captured the imagination of the world. And General Robert Baden-Powell, later to found the Boy Scout movement, with his British garrison resisted the Boer assault.

Helen and Gordon introduced Molly to General Baden-Powell, who put her in charge of the children's hospital as she had some basic nursing skills. I remember as a child being so proud of my granny. She put together a makeshift hospital where she nursed the wounded, both Boer and British. My mother, equally proudly, told me that for this and other acts of courage she was awarded the Royal Red Cross, the women’s equivalent of the Victoria Cross, for highest bravery. Later in the war when Baden-Powell had taken up command of the British troops in the Free State town of Bloemfontein, he asked Molly if she would come and nurse the Boer women and children following the scorched-earth policy of the British by which they burned down hundreds of Boer farmsteads and took the women and children captive.

Also in the Free State was a certain English cavalryman, Captain Edward Reading, who was gearing up for a battle against a strong Boer force. Although the British carried the day, Edward was wounded and moved to a hospital in Bloemfontein where he was capably looked after by nurse Molly Craufurd. They fell in love and the rest is history.

After Edward, or Ted as he was known, and Molly married, Ted joined the British South African civil service. They both had profound regrets over the Boer War and saw it as an unnecessary and tragic consequence of Britain’s empire-building. Their view was that this had achieved little and turned the Boers into implacable enemies of Britain.

I well recall Ted and Molly impressing on me that the Anglo-Boer War was a tragic mistake and that military and political greed brought only bitterness and the desire for vengeance.

After the horrors of the war Grandpa, or ‘Dah’ as I called him, and Granny Reading were posted to the Free State town of Parys where Dah took up his first magistracy. Mum and her twin sister were born in 1906, Mary Tyrell and Mary Craufurd, who were nicknamed Tweedledum and Tweedledee. Mum was known as Dee all her life. They were inseparable best friends so my mother was inconsolable when Dum died of pneumonia in 1910 at the age of five. I don’t believe Mum ever recovered fully from this heartbreaking loss.

Dee’s parents – Molly and Ted (Edward) Reading

But life had to go on. In 1910 Dah was transferred to Heilbron, another Free State town and not that far from Parys, again as the senior magistrate. There he established a friendship with Deneys Reitz, the legendary Boer general. Out of this friendship the two former combatants taught each other much about reconciliation and forgiveness.

In fact, in my office I have a framed letter from Deneys Reitz to my grandfather in which he writes:

The fact that I was able to speak of ‘battles long ago’ without bitterness as early as I did was largely thanks to you. When first I came to Heilbron I still nursed a good many narrow prejudices and I might easily have followed a far more rigid pathway than I did but for your having been my friend.

I am thankful to know that the road you and I have trod is now being justified by racial concord such as this country has never known and to you personally I owe an eternal debt of gratitude which this letter is a feeble attempt to express.2

This letter followed Reitz’s self-imposed exile to Madagascar where he had struggled for a couple of years with his bitterness over the British. Dah seemingly played a significant role in persuading him to return to South Africa.

Dah was then made Chief Inspecting Magistrate and Inspector of Prisons for South Africa. This kept him and his little family constantly on the move all over the country in what my mother as a child felt was ‘a wretched existence’.

After initial education from a private governess, Mum went to boarding school at Roedean, Johannesburg, which gave her some stability, and she did well with her schoolwork, and even opened the bowling for the school cricket team! She was head girl for her last two years and also developed her extraordinary gift for the piano. In her final school concert she played Beethoven’s ‘Appassionata’, one of the more demanding sonatas, from memory. This opened the way for her to go to the Royal College of Music in London, after which she returned to Roedean (in Johannesburg: the sister school of the one...