This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

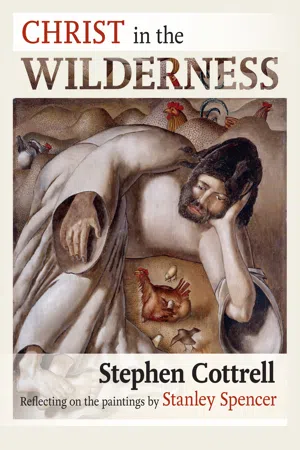

In this attractive illustrated book, Stephen Cottrell reflects on five of the Christ in the Wilderness paintings, and reveals them to be a rich source of spiritual wisdom and nourishment. He invites us to slow down and enter into the stillness of Stanley Spencer's vision. By dwelling in the wilderness of these evocative portraits, Stephen Cottrell encourages us to refine our own discipleship and learn again what it means to follow Christ.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Christ in the Wilderness by Stephen Cottrell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christianity1

Rising from Sleep in the Morning

Christ in the Wilderness: Rising from Sleep in the Morning (1940)

State Art Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia. © The Estate of Stanley Spencer 2012. All rights reserved DACS.

I don’t find praying easy. On the one hand I truly believe that it is the most important thing I do each day. On the other hand, finding the discipline to match the desire is never as straightforward as I would like it to be. This is especially true when I am left to my own devices. There always seem to be good reasons to put off praying, or, when I do set time aside, my mind wanders, or I gallop through words that should be taken slowly, gulp down without chewing what needs to be savoured. I long for the intimacy and focus of prayer I see in this picture. Because for Jesus, prayer seems, for the most part, to have been joy. What we see here is not some solemn obligation or duty that has to be got through, but the delight of coming into the presence of the Father. The whole of Jesus’ body is directed upwards to God, like an arrow pointing to the heavens.

Unlike some of the other pictures in this series, it is not possible to be sure which passage of Scripture Spencer had in mind when he painted this image of Jesus. There are several possibilities. In the Gospels Jesus often disappears, both to get away from the crowds (and his own disciples!) and to spend time with God. Indeed, it is this closeness to God that is most startling about his ministry. He is the one who calls God ‘Father’.

Sometimes today people understandably have difficulty with the almost exclusively male language that the Bible uses to describe God. But there are exceptions, and one of them is the last picture we will look at in this series. However, we cannot avoid the intimacy of the language Jesus uses. In fact the Aramaic word that Jesus uses – Abba – is much more like the child-like ‘Daddy’, in contrast with some of the rather sterner connotations that the English translation ‘Father’ might suggest (see Mark 14.36, Mark’s account of the Gethsemane story, where Jesus calls God Abba). This tenderness towards God was shocking to those who heard him, as it can still be shocking for us today. And even if you are one of those people who have had bad experiences of fathers, I hope that Jesus’ revelation of God as the loving parent, the one in whom we can enjoy intimacy and communion, can be received as a precious gift to release us from the harder, more limiting patriarchal images that distort the radical simplicity of what Jesus was actually teaching.

What we see in this picture is a child delighting in the presence of the one in whom he is able to be completely himself. This is what a relationship of absolute love and trust gives us. We are set free to be ourselves; and even if life has never afforded us this sort of relationship, then it is on offer through that relationship with God that Jesus is making possible. Can we begin to discern in this picture the tiny child whose hands reach up in delight when its mother enters the room?

We may also note that right at the beginning of the Gospel story, as Jesus’ ministry commences and he submits to John’s baptism as a sign of his solidarity with all of sinful, broken humanity, the voice of God speaks from heaven to proclaim that this Christ, this man from Galilee who to all intents and purposes seems like any other man, is actually the Son of God: God entering the creation he has made; and not only a son, but a beloved one, in whom God is well pleased (see Mark 1.9–11). Many New Testament commentators have observed that this great affirmation of the Father’s pleasure is the dynamic out of which Jesus’ whole ministry flows. He knows that he is the beloved of God. He never doubts it; and even when the going gets very tough indeed, and he longs for there to be another way, he is still rooted in this relationship of trust and love.

It is a relationship that sustains him. It is a relationship that he turns to every day. In the very first chapter of Mark’s Gospel, following a day of intense and fruitful ministry, we also read this: ‘In the morning, while it was still very dark, he got up and went out to a deserted place, and there he prayed’ (Mark 1.35). Since this verse speaks of a deserted place it already recalls the wilderness. It is therefore most likely that this was the piece of Scripture Spencer had in front of him when he began this painting. If this was the case, it is interesting that this passage not only tells us of Jesus’ great desire to spend time with the Father, it also illustrates the fruitfulness of a prayerful life, for we are told in Mark 1.36 that ‘Simon and his companions hunted for him’. There are clearly still people in Capernaum, where Jesus was ministering the day before, who need his presence: ‘Everyone is looking for you,’ Simon says (Mark 1.37). But astonishingly Jesus turns his back on these needs. He says no to Simon’s request. ‘Let us go on to the neighbouring towns,’ says Jesus, ‘so that I may proclaim the message there also; for that is what I came to do’ (Mark 1.38). Somehow the intense focus of Jesus’ prayer has created within him a clarity of purpose and a conviction about what must be done and what must be left undone. This is not itself the purpose of prayer, but it is the fruit of a prayerful life.

There is an alignment between the will of God and Jesus’ own will. We should not think of this as easy or obvious (saying to ourselves that because he is God’s son then of course he knew God’s will). As we shall explore in a later chapter, the wilderness is for Jesus a place of encounter and temptation. Who Jesus is as God is contained and coterminous with what he is as a man; therefore he knows choice and with choice temptation, just as we do. In Gethsemane he pleads with God that other choices might prevail. Here it would have been possible to please both Simon and the crowds, and do the obvious thing and go back to Capernaum. But Jesus is in touch with a higher agenda, a compelling sense of God’s call upon him and knowledge of God’s choice in that situation. This knowledge was not something that came to him automat-ically, however. It had to be worked at, discovered and discerned. Therefore he rises early each morning, and he seeks out the wilderness, the place where everything is stripped back, in order that he might find communion with God and seek God’s will.

Consequently, you can see that Spencer has painted Jesus in an intensely focused posture. His eyes stare towards heaven. His hands reach upwards in a gesture that combines praise and longing. He is reaching out to receive. He is pointing his whole body towards God.

There are different ways of reading all these paintings. Here Jesus is in what appears to be a crater. It is almost as if he is a missile about to blast off. Just as the Spirit drove him into the wilderness, now he is himself about to be propelled to God. Or, some people see his posture as being like a church spire, pointing to the heavens.

Most people observe that Jesus looks rather as if he could be a flower. As far as we know this was in fact Spencer’s intention, although it may have been, even for him, a subconscious one, since it was only later that he made the connection. Speaking about the paintings years after they were finished, he said, ‘I think I was, perhaps thinking of a flower opening.’1 He also said:

Christ liked to feel the fact that he was a man and that he might do a lot of the normal things that a human might do, such as going to bed and getting up in the morning: that it would be a very wonderful experience – that it would be, so to speak, the first getting up of a human being – almost like a rehearsal of the act – that the joy would consist in the waking and the awareness of his great lover ‘God’.2

This shows how Spencer liked to see Christ living out God’s delight in the creation. Remembering his wartime experiences in Macedonia, Spencer also notes that the crater Jesus rises from is like a shell-hole.

In this reading of the picture Jesus’ arms reach upwards like the stamen of a flower and his robes are splayed out around him like the petals. This is what prayer is like, the painting seems to be saying. It is normal. It is natural. Just as a flower opens its leaves and its petals to the sun on a new day, so Jesus rises from sleep to pray.

Prayer won’t always feel normal, it won’t always feel natural – and that has certainly been my experience – and yet it should be, for we human beings are made for community with God. It is for this sort of intimacy with God that we are intended. Therefore our restless hearts will only find true rest and true peace when they allow themselves to be embraced by this communion with God.

And why does a plant open its leaves and petals to the sun on a new day? Well, it is part of that process whereby a plant creates energy for life. The leaves receive the energy of the sun. The brightly coloured petals attract. Although this is also true for prayer – when we pray we receive the energy we need for living – it is not the reason we pray.

The purpose of prayer is praise: not because God needs our thanks, but because without God there is nothing. Once we catch a glimpse of who God is, and realize the fact that each breath we take is a gift from God, then what can we do but pour out our thanks at the amazing miracle that life itself exists at all; within the precious oasis of this mysteriously beautiful planet, conscious life can reflect upon the fact of existence, and cry out in wonder and amazement. Prayer, then, is simply our stumbling thanks for all that God has already done. That we are here at all is amazing. That we are able to reflect upon our existence is miraculous, and made even more astonishing the more we learn from science about the fragile equilibrium of the universe and our own delicate part within it. How could we not give thanks?

But if there is a God who has made us, and who loves this creation and has a special care for us, not only as part of the creation but as the one part that is able to return praise (as far as we know), then the voice of our thanksgiving must soon turn to silence. For if in prayer we can know and give thanks to God, then we can also receive from God. Our minds and hearts can be fed and replenished; we can begin to know God’s mind; there can be alignment between our own wills and the will of God. This sort of prayer has several names. It can begin as contemplation: simply resting in the presence of God and quietly giving thanks for who God is and the gifts of life we have received. But it can move to a more active meditation, where we ask God that we might know God’s purposes for our lives and for the world.

This focused receiving from God is what we see in this picture. If Jesus is painted as a flower, then this might be a lotus flower. In Tibetan Buddhism this flower is a symbol of prayer, particularly connected with purification of body, speech and mind, and the full blossoming of wholesome deeds. I don’t know whether Spencer had such a parallel in mind, but within the Christian tradition, and brilliantly captured in this remarkable painting, prayer is portrayed as the vital defining characteristic of Jesus’ life and ministry. It is reasonable to conjecture that this was something Jesus was schooled in before his ministry began. He broods upon the Scriptures. He attends to the worship of the synagogue. He gives himself to places of receiving. This is what the flower is doing.

However, as I look again at the painting I am also reminded of bindweed, whose white, bell-shaped flowers we used to call, as children, ‘granny pop out of beds’. The flowers have a remarkable playfulness – when you pinch the head of its stem the flower jumps forth, as if propelled to the heavens.

Whatever flower you see in this painting, we know that in order to flourish, every living plant must be established in good soil that feeds its roots. There is the hidden strengthening that is going on beneath the ground as well as the glorious apparel of the flower itself. This is also true for prayer, where we need ‘good soil’: the habits and disciplines of time set aside for prayer and a sifting of words and methods so that we find the way of praying that suits us best and feeds us so that our faith blossoms and flowers. The paradox in this painting is that the ‘good soil’ for Jesus’ praying may deliberately be a shell-hole. But this shows us that prayer can never be separate from the conflicts and sufferings of the world. In fact, it is...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Title page

- Imprint

- Dedication

- Preface

- Table of contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Stanley Spencer and me

- 1. Rising from Sleep in the Morning

- 2. Consider the Lilies

- 3. The Scorpion

- 4. The Foxes Have Holes

- 5. The Hen

- Afterword: Contemplation and desire – reading the art and spirituality of Stanley Spencer

- Notes