This is a test

- 426 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Marxism-Leninism and the Theory of International Relations

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Refuting the assumption that orthodox Marxist theory contains anything of relevance on international relations, this book, originally published in 1980, clarifies, reconstructs, and summarizes the theories of international relations of Marx and Engels, Lenin, Stalin and the Soviet leadership of the 1970s. These are subjected to a comparative analysis and their relative integrity is examined both against one another and against selected Western theories. Marxist-Leninist models of international relations are fully explored, enabling the reader to appreciate the essence and evolution of fundamental Soviet concepts as such as proletarian, socialist internationalism, peaceful co-existence, national liberation movement and détente.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Marxism-Leninism and the Theory of International Relations by V. Kubalkova, A. Cruickshank in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introductory: basic assumptions of theories of international relations

My hunch is that the quantitative-qualitative data gulf is not so unbridgeable as differences of commitment to various ways of knowing – more particularly opposed notions of what it is possible to know.

Richard C. Snyder

It has become almost a tradition to assume that the East-West divide runs as deep as is the sphere of intellect, and that the thinking of each side follows paths incomprehensible to the other. Because of that and before we begin to talk about their respective theories of international relations we have to pause for a while and consider what can be meant by a theory to both East and West. In other words we shall try to forget the divide and instead speculate in general terms as to what the word theory can mean before we proceed in succeeding chapters to the question of what it is by each side supposed to mean.

The word 'theory' has been used so vaguely and indiscriminately within the perimeters of social science that it has virtually lost such meaningful content as it once possessed.1 Indeed it would be possible (and perhaps useful) to come up with a 'theory of theories' that would cover all possible meanings of the term since the time when it meant no more than 'the action of observing'.2 Although 'theories of theories' may well stand to become the most abstruse of all international theories,3 they remain nevertheless as important and as essential as any of the others.

If we could speak of such a thing as a 'theorology' applied to the field of international relations, it would have to be placed at the junction of some six disciplines: philosophy, epistemology, sociology, politology, political philosophy, and logic. In other words, the arbitrariness of divisions into these disciplines, notwithstanding any venture in theory building in international relations, has to come to terms with some of the basic questions that are traditionally associated with these disciplines. This is perhaps one of the most fascinating features of international theory; that it no more stops (or should not stop) at the boundaries of states than it is restricted by disciplines – or ideologies. Whether the theorists pay any attention to these questions, consciously or unconsciously, explicitly or implicitly, evading or trying to evade any of them, they cannot help but express their attitudes towards them. Talking about laws regulating international relations – or their absence; choosing a particular aspect for purposes of explaining a certain range of phenomena; delineating the width of this range; using quantitative methods; rejecting values; working for peace, etc., lead into much deeper water than would seem at first to be the case – or than some authors would willingly wish to enter. As regards disclaimers of meddling and of refraining 'from attempting to settle the profound questions of epistemology which have remained unsettled for centuries'4 one should not confuse two separate things: there is a difference between 'attempting to settle' those questions on the one hand and, on the other, keeping them in mind, where the latter does not necessarily imply the former since, after all, those questions may not be 'resolvable' in the sense that is usually accorded to this word. What could be 'settled' however, even at the highest level of discussion of theory building, is the problem of putting an end to the absence of a clear distinction between and among all these various aspects of a theory, and settling the confusion that results from mixing them or of emphasising some at the expense of others – a process that makes infinitely more perplexing the theories themselves as well as creating problems for their exposition. How can a debate lead to any meaningful conclusions if, for example, one side attacks a theory in epistemological terms and is replied to in terms of its logical virtues?

Since we have set out to juxtapose the international theory of the West and that of the East, a 'theorological' exercise is absolutely essential. Only by accepting the broadest preliminary assumptions can we hope to find the roots of the basic differences and account for the similarities.

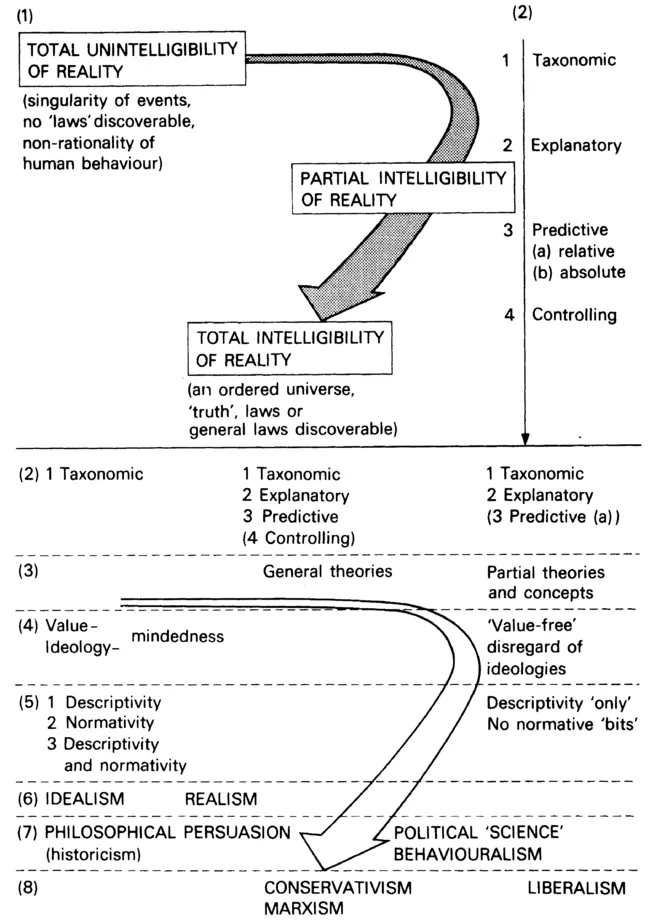

Since a degree of correlation among the attitudes to the above mentioned groups of questions has been admitted or is implied, the attempt (Figure 1) to make this correlation more obvious in a graphical and hence heavily oversimplified manner might be

Figure 1 Assumptions of theories of international relations (a continuum)

considered worthwhile. Figure 1 is to be understood as a continuum with a preponderance of border cases over those that fall within clear-cut extremes of black or white. In the course of this chapter, recurrent reference will be made to Figure 1 as section succeeds section (the numbers in brackets are the respective section numbers in that figure). Furthermore, since we may expect a shared concern on the part of various disciplines in regard to some questions, we shall refer to them where the boundaries are not always clear and no direct comparison between East and West is at issue, as simply 'groups of questions', without the arbitrary superimposition of disciplinary barriers.

To begin with then, let us observe that the definition of the term 'theory' itself – that is to say the establishing of what the term conveys – is an epistemological exercise5 par excellence. And, since contemporary epistemology is no longer the preserve (as was its classical antecedent) of philosophy alone and tends to be found throughout the sciences in the form of discussions on 'basic issues' and reflections on the history of each discipline,6 international theory must, alongside other branches of social science, take cognisance of this expanded range and application where theoretical first principles are in debate. Suffice it to say that the expanded interdisciplinary application of epistemology referred to ranges from the 'basic issues' of psychology (in so far as questions of fact – that are ipso facto the affair of epistemology – inevitably involve questions of perception, associations, psychological formations of ideas and so on) to those issues of logic beyond the basic questions of validity (relationship between subject and object and how knowledge is to be made to relate and come to terms with the real world, etc.) with which that particular discipline deals.

Though we experience no difficulty in finding a preliminary and workable definition of theory in, for example, 'an integrated set of statements about some phenomena under observation', as soon as we begin to try to determine what the function of such a 'set of statements' can be we must expect to become involved in a philosophical debate. Questions that probe the reality of the external world, the nature of mind, the nature of their mutual relationship –and all of these in search of an answer to the basic questions: How far is reality intelligible? How much can we ever hope to know? Questions that are age-old and have been answered in so many different and often conflicting ways by various philosophical schools. Let us however for our purposes content ourselves with the simplification of the argument. Basically the answers given fall into one of three categories, with many shades of attitudes between. These are as follows:

- The phenomenon of international relations is so complex that its comprehension is beyond human capacities. Our grasp of it is erroneous and confused; international relations theory like other 'social sciences' can never become a science in the sense of its consisting of knowledge that is verifiable, systematic and general. The events are singular; therefore no 'laws' are discoverable. All we can ever hope for are 'theories' that are no more than 'a conglomeration of plausible folklore'7 (see Figure 1, section 1).

- Reality is totally intelligible, there is nothing a priori incomprehensible, although there are areas not as yet comprehended. There are discoverable regularities or patterns of behaviour, hence 'laws', even 'general laws', can be identified.8

- There is only a partial possibility of understanding reality since only the occurrence of certain regularities may be observed.

Correlated with these attitudes is the perception of the role that a theory can fulfil (Figure 1, section 2). Thus international relations theory is variously seen as being able to serve these purposes:9

- Taxonomic, consisting of classification of data (i.e. arranging them into items on the basis of some stipulated quality which they share) in such a way that similar sets of data may be similarly arranged, and compared.

- Explanatory (generally based on the above), consisting of definitions of (a) variables into which data may be organised (b) relationships between variables with some degree of precision, and, where possible, introducing quantification.

- Predictive, consisting of anticipation with some degree of probability of the occurrence of certain variables and relationships in the future. To produce:

- (a) relative predictions: There is a probability of C per cent that condition A is associated with effect B.

- (b) absolute predictions: Condition A is always associated with effect B.

- Controlling, consisting of influencing and/or manipulating the occurrence of predicted events. It should be noted that it does not follow that having achieved purposes 1-3, the theory can become ipso facto a basis for controlling the phenomena; in this regard Oran Young points out that although we have an excellent theory of the dynamics of the solar system we still have very little ability to manipulate its variables.10

The following statements from current Western literature on international relations show that the correlation of philosophical assumptions with the aims of theory as indicated above is acknowledged.

Kaplan, apropos of the objects of international relations theory, states:

to discover laws, recurrent patterns, regularities, high-level generalizations; to make of predictability a test of science; to achieve as soon as possible the ideal of deductive science, including a 'set of primitive terms, definitions and axioms' from which 'systematic theories are derived'.

to which Hoffmann replies:

These objectives are the wrong ones. The search for laws is based on a misunderstanding by social scientists, of the nature of laws in the physical sciences; these laws are seen as far more strict and absolute than they are. The best that we can achieve in our discipline is the statement of trends. . . . Accuracy of prediction should not be a touchstone.11

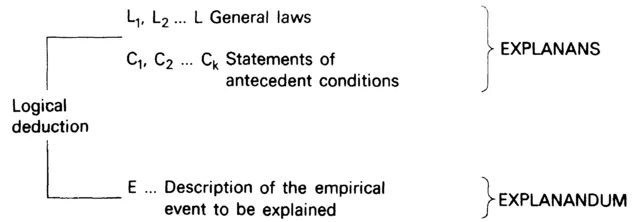

Prediction is often based upon approximately the same elements as explanation but there are sufficiently serious practical differences between the two as to throw some doubt on the validity of claims to their congruency made by those theorists who consider the principal object of theory to be prediction. Those who do not so consider prediction to be a central aim generally distinguish it from explanation. This difference is easier to understand in Hempel's 'pattern of scientific explanation' (see p. 7):12

If E is given and a set of statements C1, C2 . . . and L1, L2. . . Lk is provided afterwards, we speak about explanation. If, on the other hand, the statements C1, C2. . .Ck are given and E is derived prior to the occurrence of the phenomenon it describes, we speak about prediction. Hempe's thesis that an explanation is not fully adequate unless its explanans, having been taken into account in time, could have served as a basis for predicting the phenomenon under consideration, is not generally accepted and, in international relations theory in particular, it would 'invalidate' a great number of 'explanations'.

Similarly, we encounter the most varied views concerning the nature of and relationship between prediction and explanation, as well as the place of both of them in social science.

There are many questions arising from Hempel's scheme, the most obvious of which are:

- What is the nature of 'statements of antecedent conditions' (C1, C2, . . . Ck). Hempel himself distinguishes between deductive and statistical ones.

(Deductive: All F are G, Statistical: Almost all F are G, x is F, x is F, x is G x is almost certainly G) Thus statistical statements do not guarantee that the event to be explained or predicted is a logical consequence of statements. It is obvious that a great number of statements about international relations will be of this nature, at least for the time being. - How many such statements C1, C2, . . . Ck are required; in other words, what is 'k'? Hempel assumes that one should be able to establish laws, indeed general laws, the acceptance of which depends entirely of course on the philosophical assumptions. (It should be noted here that recently, even in the field of natural science – physics in particular – many cases have been observed where the 'laws' failed to work and doubts about the predictive capacities of the natural sciences have been expressed.)

Most international relations theorists in the West agree that international relations theory has managed so far to meet only the requi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introductory: basic assumptions of theories of international relations

- 2 Marx and Engels on international relations

- 3 Theory of international relations in the East

- 4 The East and Marx

- 5 International relations theory in the West and in the East

- 6 International relations theory in the West: Marx and Lenin

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Chronology of the main works of Marx and Engels

- Appendix 2 Karl Marx: A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy

- Appendix 3 Chronology of the main works of Lenin (1870–1924)

- Appendix 4 Constitution (Fundamental Law) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

- Appendix 5 Selective chronology

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index