![]()

1 Ruskin's theory of wall (veil)

Architecture of flatness

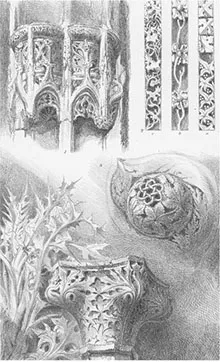

In Seven Lamps, Ruskin defined architecture as ornament. He declared architecture as the addition of “certain characters venerable or beautiful, but otherwise unnecessary” (Ruskin 1903–1912, vol. 8, p. 29). He argued that to determine the “height of a breastwork or the position of a bastion” was not architectural. However, if “to the stone facing of that bastion be added an unnecessary feature, as a cable moulding, that is Architecture” (ibid., emphasis original)”. The emphasis on superfluity was to ensure that ornament was “above and beyond its common use”, meaning that it was not limited “by any inevitable necessities, [in] its plan or details” (ibid.). This was also reinforced in a later publication, where he observed that in the Basilica of San Zeno, Verona, the “pleasantness of the surface decoration is independent of structure; that is to say, of any architectural requirement of stability”, and could well be compared to “a piece of lace veil . . . suspended beside its gates on a festal day” (ibid., vol. 20, p. 216). It was not just the superfluous, but also the surficial and the fragment that Ruskin always seemed focused on. This can be seen in Seven Lamps that presented an account of medieval buildings as a series of collages, of fragments severed from the context of the building (Figure 1.1). The focus on surface fragments was sustained in all volumes of Stones, which presented profiles and elevations of archivolts, jambs, bases, cornices and capitals from different buildings, composed into a single image, representing a comparative study of parts. To this end, Ruskin’s definition and representation of architecture ( and ornament) appeared to be embedded in a series of overstatements around the aesthetics of superfluity. This invited criticism from Ruskin’s contemporaries, who saw this as the confirmation of his lack of training as an architect.

Samuel Higgins (1853, p. 723), one of the well-known commentators on Ruskin, defined architecture as the “art of the beautiful manifested in structure”. Hence, a “building in which construction is made subservient to, and whose chief glory is colour, whether obtained by painting the surface, or by incrustation with precious and coloured material, cannot be architecture at all, in the proper sense of the word”. An anonymous reviewer echoes this view by arguing that focusing on the ornament instead of the structure, is to “describe the coat instead of the man, sometimes not even the coat, but the buttons and braid which cover it” (Anonymous 1853). Twentieth-century views were not very different. For Charles H. Moore, Ruskin’s “apprehensions were not grounded in a proper sense of structure and he had no practical acquaintance with the art of building” (Moore 1924, p. 117). And even though he appeared to discuss Gothic, Moore argued, he seemed to think of its consisting “virtually in ornamental features—even structural members bring regarded him as of primarily ornamental significance” (ibid.). He adds further that even though Ruskin “says a great deal about structure”, he does not fully grasp the “exigencies of the total structural system. In discussing these things he makes emphatic affirmations that involve important errors” (ibid.). Paul Frankl echoed this in his authoritative publication The Gothic: Literary Sources and Interpretations through Eight Centuries (1960), in which he maintained that Ruskin did not really understand important advancements in architecture like the ribbed vaults, because he could not adequately visualize or understand three-dimensional interiors (Frankl 1960, pp. 560–561).

Figure 1.1 John Ruskin, Ornaments from Rouen, St Lô, and Venice, from The Seven Lamps of Architecture, 6th edn (Orpington: George Allen, 1889, plate 1, p. 27).

Other twentieth-century scholars have argued that these views are not entirely accurate or fair. John Unrau points out that Ruskin’s drawing of the interior of Basilica of San Frediano, Lucca, portrayed an acute experience of architectural space and interior. Ruskin’s drawing of the interior of the loggia of the Ducal Palace (1851) captured the spatial qualities of a semi-open space. Unrau (1973) also points to Ruskin’s interest in the vaulting in French medieval buildings. He illustrates a page from Ruskin’s rough notebooks, which showed that he made diagrams and notes about the vaulting of French medieval buildings. It also showed that he had taken notes on Gothic vaulting from Robert Willis’s Remarks on the Architecture of the Middle Ages, Especially of Italy (1835). Unrau considers the following passage from The Bible of Amiens (1880–1885), to demonstrate Ruskin’s dynamic appreciation of the interior:

I know no other which shows so much of its nobleness from the south interior transept; the opposite rose being of exquisite fineness in tracery, and lovely in lustre; and the shafts of the transept aisles forming wonderful groups with those of the choir and nave; also, the apse shows its height better, as it opens to you when you advance from the transept into the mid-nave, than when it is seen at once from the west end of the nave; where it is just possible for an irreverent person rather to think the nave narrow, than the apse high.

(Ruskin 1903–1912, vol. 33, p. 129)

This was one of many instances. Paul Hatton (1992, p. 129) echoes this defence, but he fittingly asks: “In Ruskin’s case, awareness and interest must not be confused. The appropriate question which arises is that if Ruskin can be shown to be capable of appreciating space, why did he choose to give priority to the quality of facades”?

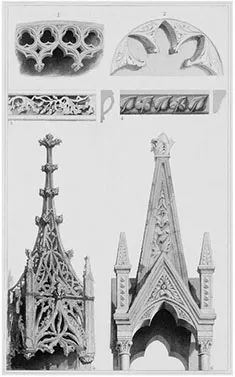

One reason can be the emerging Victorian architectural aesthetics of massiveness and substantiality. Edward N. Kaufman observes that the ecclesiological fervour in Cambridge and Oxford gave rise to a new style of country churches that were characterized by “low walls and high roofs, rough textures and picturesque articulation” (Kaufman 1982, p. 95). Kaufman explains that George Truefitt captured these ideas in his Designs for Country Churches (1850), in which the country churches were depicted as “compact, angular, and assertive”, but above all, as “massive”, not in the sense of displaying sturdiness, but possessing a sculptural quality (Kaufman 1982, pp. 95–96). Architects like George Gilbert Scott, George Edmund Street, John Pearson, and George Bodley who took up this language, appeared to strive “towards an ideal of pure mass” (ibid., p. 96). The new language sought to suppress “hollowness and permeability”, and create a record in stone of the “impenetrable weight and substance” (ibid., p. 97). Kaufman argues that Ruskin, more specifically his “Lamp of Power”, was an important force in this movement. Michael Brooks reinforces this view. He explains that for Ruskin too, mass meant that a “building should convey a sense of the quantity and weights of its materials. Its walls should be thick and its doors and windows recessed so that this thickness will be dramatized” (Brooks 1989, p. 78). Indeed, Ruskin did say that the “majesty of buildings depends more on the weight and vigour of their masses, than on any other attribute of their design: mass of everything” (Ruskin 1903–1912, vol. 8, p. 134, cited in Brooks 1989, p. 78). This informed his preference of “Surface Gothic” over “Linear Gothic”; the fourteenth-century Tomb of Cansignorio della Scala in Verona over the niches in the Saint-Vulfran Cathedral in Abbeville; and the solid surface of the geometrical plate tracery in early English Gothic over the flexible and sinuous network of traceries in Perpendicular Gothic (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 John Ruskin, Linear and Surface Gothic, plate from The Stones of Venice, volume II (mount size: 702 × 510 mm, sight size: 482 × 312 mm). Printmaker: Richard Parminter Cuff. Collection of the Guild of St George, Museums Sheffield. Image courtesy Museums Sheffield, accession number CGSG01588.

It is also possible that Ruskin’s interest in surface was connected to his (over) familiarity with the visual language of Venetian buildings. Garrigan argues that it is “impossible to say whether Ruskin’s architectural emphases were at least partly suggested by his early love of Venice or whether he was attracted to Venetian architecture because it so richly exemplified the qualities that were innately appealing to him” (Garrigan 1982, p. 154).1 She explains that the “city’s tightly circumscribed island geography” gave rise to buildings that had planar and flat facades (ibid., p. 154; see Figure 1.3). These façades could be “analysed and appreciated as isolated planes”, as the buildings did not display structural complexity (ibid., p. 155). Garrigan (1973) had explained in an earlier publication that Ruskin was interested not just in walls but in their planarity. She claimed that he viewed a “building as a series of planes”, which “may be undecorated, beautiful in themselves because of the lovely patterns inherent in their materials” (ibid., p. 42). This explained his admiration for Italian Gothic, which was marked by volumetric clarity and “serene resolution of horizontal and vertical elements”, as well as his ambivalence towards Northern Gothic cathedrals, known for their sculptural intricacies and interpenetrative volumes. The Chapter argues that Ruskin did not merely have a surface obsession: he re-introduced the concept of the wall in its entirety, suggesting a considerably original course for nineteenth-century architectural theory.

Figure 1.3 Palazzo Priuli, Venice. Photograph by Anuradha Chatterjee, 2004.

Ruskin was not the first to propose a theory of architecture based upon the wall. In De Re Aedificatoria, Leon Battista Alberti suggested that columns emerged from the wall; that the column was defined by what was left after the wall was pierced; and that the wall was the basic element of architecture. He said:

When considering the methods of walling, it is best to begin with its most noble aspects. This is the place therefore where columns should be considered, and all that relates to the column; in that a row of columns is nothing other than a wall that has been pierced in several places by openings. Indeed, when defining the column itself, it may not be wrong to describe it as a certain, solid, and continuous section of the wall, which has been raised perpendicularly from the ground, up high, for the purpose of bearing the roof.

(Alberti 1988, p. 25, emphasis added)

Rudolf Wittkower argues that Alberti’s theory was a misreading of the Greek column, which “always remained a self-contained sculptural unit”. Wittkower explains that Alberti did not know Greek buildings (Wittkower 1988, p. 30). He knew mainly Roman imperial architecture, which was basically “wall architecture with all the compromises necessitated by the transformation of the Greek orders into decoration, but in many cases it still retains the original functional meaning of the orders” (ibid., p. 34). Alberti reconciled the conflicts between the two systems, to develop a consistent “logic of wall architecture”, expressed powerfully in San Sebastiano and San Andrea” (ibid., p. 49). Alberti is relevant because Ruskin was influenced by him. Cornelis J. Baljon observes resonances between Alberti’s De Re Aedificatoria and Ruskin’s Stones of Venice, and describes one of the highlights:

Architecture in both is approached in terms of stone walls rather than of beams and lintels. The various parts of a building (foundations, walls, ceilings, vaults, and roofs), severally of a wall (base, “wall veil”, cornice) and openings therein, are first discussed constructively, next with regard to what decoration best suits each part.

(Baljon 1997, p. 406)

It is no surprise then that Ruskin too presents his own theory of the wall. Actually, the correct term was “wall veil”, which was the “even portion of a wall” in any structure, in between the piers and the buttresses, and “generally intended only to secure privacy, or keep out the slighter forces of weather”. Ruskin used the term wall veil as he found it to be “more expressive than the term Body” (Ruskin 1903–1912, vol. 9, p. 80). Nevertheless, the wall veil was a mechanical element of a building, which had to be “decorated” or adorned for it to become part of the language of architecture.

In “The Six Divisions of Architecture”, Stones I, Ruskin claimed that the wall was one the three elements that constituted architecture: the other two elements were roof and apertures. In addition, he dedicated four chapters to the wall (“The Wall Base”, “The Wall Veil”, “The Wall Cornice”, and “The Wall Veil and Shaft”), with the rest of the chapters focusing on illustrating and discussing surface details, wall decorations, and profiles of elements. Considered together, the textual and graphic documentation marked the development of a new language—that of ‘surface architecture’. In Seven Lamps, Ruskin defended the wall as the only element in architecture that was worth considering. He argued:

Of the many broad divisions under which architecture may be considered, none appear to me more significant than that into buildings whose interest is in their walls, and those whose interest is in the lines dividing their walls. In the Greek temple the wall is as no...