![]()

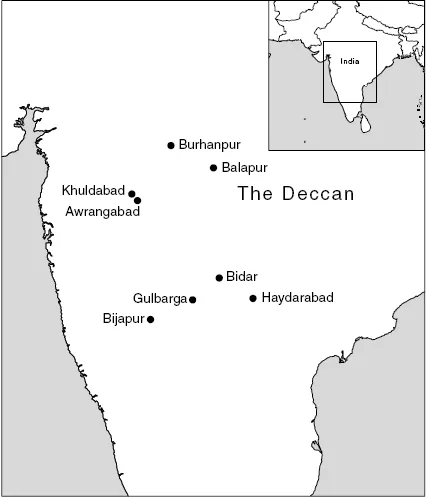

Map 1 The Deccan (inset): India

Source: Courtesy Collins Bartholomew Ltd 2005. Digital data with permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

![]()

1

MUSLIM MYSTICS IN AN AGE OF EMPIRE

The Sufis of Awrangabad

As soon as he started to build there, Awrangzeb renewed the country of the Deccan with the buildings of Awrangabad, which is one of the great cities of the world. Its suburbs are also beautiful, and they sell gold there as though the sky had asked for a shop to sell its stars.1

Introduction

The city of Awrangabad was the heir to a long tradition of urban immigration and cosmopolitanism in the southern region of India known as the Deccan. In 1019/1610 the city was founded in the name of the Nizām Shāh rulers of nearby Ahmadnagar by a former Ethiopian slave, Malik ‘Anbar.2 In this first incarnation, under the name Khirki, Awrangabad stood as the last major city to be founded by the independent sultanates of the Deccan prior to the region's conquest by the Mughal empire of Hindustan (in precolonial usage, North India as opposed to the Deccan). But in spite of this early history, Awrangabad would owe its fame, name and subsequent architectural as well as broader cultural and religious character to the period beginning with the Mughal defeat of the Nizām Shāhs in 1047/1637.3 After the initial Deccan conquests of Shah Jahan (commanded by the youthful Awrangzeb), following his own accession to the Mughal throne Awrangzeb moved his court to the Deccan and refounded the city in 1092/1681.4 His choice of the city as the centre for his wider conquests of the independent Muslim kingdoms of the Deccan was perhaps fitting, for the migrant Persian geographer Smdiq Isfahmnl (fl.1045/1635) had earlier interpreted its name of Khirki as signifying the ‘gateway’ opening onto the Deccan.5 What was in the eyes of its conquerors the good fortune of the city also soon earned it the sobriquet of Khujista Bunyād, ‘the auspiciously founded’. Following Mughal custom, however, Awrangzeb also honoured his new capital with his own name and it was with the royal eponym of Awrangabad that the city eventually settled.

As the royal centre of what was in this period perhaps the richest empire in the world, Awrangabad was quickly endowed with a host of public and private buildings. The most famous of these was to be the last great royal garden-tomb to be the built by the Mughals, the ‘second Taj Mahal’ built for the wife of Awrangzeb on the northern limits of the city that remains the greatest Mughal monument in the

Figure 1.1 The mausoleum of Awrangzeb's wife (Bibi ka Maqbara) in Awrangabad.

Deccan (Figure 1.1). However, imperial and sub-imperial patronage led to the construction of numerous other buildings across the city, from a royal palace designed after the models of the ‘red forts’ of Delhi and Agra to aristocratic mansions, markets, mosques and eventually shrines for the new city's emergent Sufi saints. In 1667, during the early years of Awrangzeb's reign, the French traveller Jean de Thevenot stayed in Awrangabad and penned a memorable description of its early cityscape. After pouring praise upon the recently completed mausoleum of the emperor's wife, Thevenot went on to record his other impressions of the city.

There are several other pretty fair Mosques in this town, and it is not destitute of publick places, Caravanseras and Bagnios. The buildings are, for the most part, built of Free-stone, and pretty high; before the Doors there are a great many Trees growing in the Streets and the Gardens are pleasant and well cultivated, affording refreshment of Fruit, Grapes, and Grass-plats…. This is a Trading Town and well Peopled, with excellent Ground about it.6

Numerous other foreigners visited the city over the following decades, whether European diplomats and merchants or the larger body of Christian Armenian traders with whom they usually lodged in Awrangabad. As the city gradually acquired further architectural additions to its urban topography during its period as the founding capital of the successor state of Haydarabad from c. 1136/1724 to 1178/1763 others also penned descriptions of the city. The eighteenth-century belle-lettrist and man-about-town Shīr ‘Alī Afsns (d. 1223/1808) was particularly complementary. Making a pun on the meaning of the word awrang (‘throne’, but also ‘sky’, ‘coloured paint’), he wrote that

the prince [Awrangzeb] peopled a city … and called the name of it Awrangabad, for his eyes, from seeing the colour and beauty of that city, enjoyed pleasure, and from its extent, his afflicted heart expanded at once; its air also is charming like the spring breezes, and its buildings are pleasing to every man of taste; its water has the effect of wine of grapes; every season there is good, and fresh like the spring … [I]n the gardens and woods there are also fruits of every kind, very plentiful, well-tasted and nice coloured; besides this there is always plenty of corn and lots of grain; various kinds of cloths of good texture, and good jewels, rare and costly, are obtainable at all seasons; besides this, rarities of every country, and curiosities of every land, are procurable, whenever you desire them. Its inhabitants also dress and feed well, and are generally wealthy and rich, and the beautiful ones are altogether unequalled in loveliness and coquetry.7

Before the later drain of the Maratha wars, the first decades of the Mughal presence saw Awrangabad lay the blueprint for the final phase of Mughal architectural history. Among the first projects of Awrangabad's new rulers was the building of a great palace, which the English ambassador Sir William Norris noted as towering above the urban skyline, and the girding of the city with 6 miles of walls and 12 major gates. The late Mughal architectural practices of uncovered tombs, the emphasis on architectural verticality and the embracing of the pliant possibilities of stucco took shape during the period of Awrangabad's preeminence before their eventual export to the north with the permanent return of the court to Delhi after the death of Shah ‘Alam in 1124/1712. Trade was also diverted to the city from the earlier Deccan cities by the presence of such wealth, and Awrangabad was to maintain its role as a regional entrepôt long after the Mughal princes departed, and the population of the city continued to grow through the first half of the eighteenth century. The manufacture of the embroidered silks originally purchased by the elites of empire remains the city's oldest industry to this day. Against this background, the flow of Central Asian and Hindustani dervishes had no less a colonial dimension than the conquests of the emperor himself. It remains important to stress, however, that this was not so much a Muslim colonization of a Hindu region as a Mughal colonization of a region governed for centuries by other Muslim powers. Competition and colonization, then, were directed towards fellow Muslim political and cultural rivals rather than Hindus, who as bureaucrats and traders were often significant partners in the Mughal imperial project.

Although Awrangzeb seems not to have resided in Awrangabad after 1095/1684, choosing instead to live permanently in his roving military encampment, the city retained its character as the primary military outpost of the empire's new territories. And to the extent that the city developed as an aristocratic centre it was of an expressly imperial kind. Its population during this heyday has been estimated at some 200,000, spread through no fewer than 54 suburbs.8 Laid out principally under military and ethnic criteria, these suburbs were named after the generals or communities residing there, as for example in the quarters known as Jaysinghpura and Mughalpura.9 Describing the city as ‘inhabited by many Rich merchants, ye Govermt Greate & profitable’, the English ambassador Norris stayed in one such suburb, which he recalled as ‘Coranporee’, when he passed by the city in 1701.10 Several large caravanserai were built on the edge of the city to accommodate merchants, one of which contained almost 200 domed chambers. But while commerce had certainly contributed to the city's wealth during the first decades of the Mughal presence, the city maintained a strong military dimension to its character throughout Awrangzeb's rule as the erstwhile military as well as cultural centre of a powerful and still expanding empire.

If political dissolution, literary brilliance and mystical revival have each been seen as characterizing the period of the precolonial North Indian ‘twilight’, then all these shared part of their roots in Mughal Awrangabad.11 For during its first century, Awrangabad stood at the crossroads of many of the developments that would shape the course of Indian history during the century to come. The first century of the city was played out against the background of final Mughal expansion and the subsequent fracture of the imperial realm into a number of successor states keen to draw upon the legacy of Mughal prestige. Yet it is too easy to see this period as a time of the unravelling of empire, of the fraying and rending of a grand and princely rug. The period of Awrangabad's heyday was as much one of creativity as destruction, quickened with the bustle of peoples from across Islam and India. Mughal Awrangabad witnessed the meeting of the cultures of the Indian north and south; it was the jewelled city in a blackened and war-torn landscape later witnessed by the French traveller Claude Martin; it was also a city of great opportunities. This was not only the case for Mughal generals like the future founder of Haydarabad State, Nizām al-Mulk (d. 1161/1748), for poets like the great Walī Awrangābādī (d. 1119/1707) also saw these bright possibilities.12 During its first century Awrangabad consequently acted as an important centre of literary production in Persian and Urdu, a role that has often been obscured by the later re-establishment of the literary primacy of Delhi and the rise of Lucknow and Haydarabad as its successors.

Sufis in an Age of Empire

Many Sufis also saw their fortunes as inextricably linked to those of the new city and it is against this wider literary background that Sufi writings from the city must be seen. Yet it was also amid the imperial atmosphere of Awrangabad that the lives of its Sufis were enacted. For Sufis and soldiers were frequent companions in Mughal Awrangabad, often bound together by shared faith, heritage and ethnicity no less than interwoven fortunes. Highlighted in the following account of Sufi lives in the Mughal city are associations with the royal court, the corporate nature of discipleship and the varieties of style and practice at work under the broad nomenclature of Sufism (tasawwuf). Each of these forces was of importance to the development of the shrines and the posthumous images of the city's Sufi saints. Their careers reveal the social identities of the living Sufis as well as the social contexts that formed the cradle of saintly cults. The careers of the living shaykhs described in this chapter may in this sense be seen as the pre-history of their shrine cults, whose own development and fortunes are described in subsequent chapters.

Sufism was a thriving concern in the Mughal heyday of Awrangabad. Sufis from the Chishtiyya and Naqshbandiyya, the major Sufi traditions of the day in India, as well as dervishes unattached to any specific Sufi lineage (silsila), all gathered in considerable number in the city. Interacting with the merchants, notables and soldiers of the city, many of the city's Sufis also possessed these other social identities in addition to that of a formal Sufi initiate (murīd). The number of ‘full-time’ Sufis — individuals whose social identity was constructed in exclusive terms of the dervish life — was of course smaller. Among these professionals of the soul, four Sufis emerged as the greatest capturers of large and moreover influential constituencies of followers in Awrangabad, founding the patronal associations that would help to ensure the continuation of their cults of fellowship after their deaths. These Sufis — the unaffiliated (or possibly Qādirī) Shāh Nūr, the Naqshbandl Shāh Pala...