![]()

Part I

Theoretical Foundations

Phonology and Reading

![]()

1 How Theories of Phonology May Enhance Understanding of the Role of Phonology in Reading Development and Reading Disability

Carol A. Fowler

Haskins Laboratories

and

University of Connecticut

Introduction

A theory of phonology characterizes the systematic ways in which language communities use basic language forms (for present purposes, consonants and vowels) to encode linguistic meanings. Phonology contrasts with phonetics, the study of the physical articulatory and acoustic properties of those language forms. In most approaches, the contrast between phonology and phonetics is between the cognitive or mental, and the physical (e.g., Pierrehumbert, 1990). Phonological language forms are held to be discrete, symbolic components of a language user’s linguistic competence; phonetic language forms are its continuous, articulatory, and acoustic realizations. This is not the conceptualization with which I will end this chapter, but it is one that pervades most linguistic perspectives on the sound systems of languages.

Understanding the nature of phonology is relevant to understanding reading, reading acquisition, and reading impairments. This is in part because humans are biologically adapted to spoken language, whereas reading and writing are too new (and insufficiently widespread) in human history to have shaped human evolution.

The adaptation of humans to the spoken language is evidenced by specializations of the human brain, not only for language, but, specifically, also for the spoken language, not the written language. Lieberman (1984) also suggests that the human vocal tract is adapted to speech (but see, Fitch & Reby, 2001, for another point of view). The human vocal tract differs from that of other primates in a way (a lowered larynx) that permits the production of a wide array of consonantal and vocalic gestures. The range of sounds producible by other primates is considerably more limited. A lowered larynx, other than conferring this advantage in sound production, appears maladaptive in permitting accidental choking on food; accordingly, Lieberman suggests that it must be an adaptation to speech.

That the spoken language is an evolutionary achievement of humans is also indicated by its universality. It is universal across human cultures and is nearly universally acquired within cultures. Unless children are prevented by severe hearing loss or severe mental deficiency, they learn a spoken language and learn it without explicit instruction. Literacy contrasts with the command of the spoken language in all of these respects. Many human cultures lack a writing system, and, within cultures, literacy is not universal. Children almost always have to be explicitly taught to read, and many, even when given apparently adequate instruction, fail to learn to read well.

A second reason why understanding phonology should foster understanding of reading, here particularly reading acquisition, is that the vast majority of children begin reading instruction when they are already highly competent users of a spoken language. Moreover, the language they will learn to read is typically the language they speak, albeit generally a different dialect of it. If beginning readers can learn to map printed forms of words onto the words’ phonological forms, they can take advantage of their competence in the spoken language when they read.

Both of these observations, that the spoken language, but not the written language, is an evolutionary achievement of the human species and that most novice readers already know by ear the language of which they are becoming readers, suggests that reading should be “parasitic” on the spoken language (Mattingly & Kavanagh, 1972) during reading acquisition and thereafter. Research on skilled readers bears out the latter expectation. Skilled readers access the phonological forms of words very soon after seeing the printed form (e.g., Frost, 1998); this occurs among readers of writing systems that vary considerably in the transparency with which the writing system signals the pronounced form of words.

In short, a language user’s phonological competence appears to provide an entryway or interface by which readers can access their knowledge of the spoken language, and, perhaps, their biological adaptation to the spoken language. Understanding phonology, then, may provide insights into reading, reading acquisition, and reading difficulties. In the following, I will offer some speculative insights that the study of phonology may provide into the latter two domains.

Diversity among Theories of Phonology

There are, and there have been, many different theoretical approaches to the study of phonology. In some instances, new approaches emerged from the identification of deficiencies in an existing approach, for example, when generative approaches to phonology (beginning with Chomsky & Halle, 1968) superseded descriptive (also known as structural) approaches (e.g., Gleason, 1961; Trager & Smith, 1951). However, in some cases, approaches have coexisted (e.g., autosegmental theories beginning with Goldsmith, 1976, and metrical approaches, beginning with M. Liberman & Prince, 1977), focusing on largely, but not entirely, distinct phonological domains.

In each case, issues of special interest in one approach recede in relevance or even disappear in others. For example, a central construct for descriptive linguists was that of the “phoneme,” an abstract category characterized by its role in capturing the phenomenon of linguistic contrast (see section “Descriptive linguistics”). When Halle (1959) and Chomsky (1964) identified inadequacies in the outcomes of the procedural system by which descriptive linguists partitioned the phones of a language into phoneme classes, they (Chomsky & Halle, 1968) abandoned the concept of the phoneme altogether. Their generative phonology set aside the notion of contrast, focusing instead on systematic processes that hold across the lexicons of languages (see section “The generative phonology of Chomsky and Halle (1968)”).

I will take the view here that the successes and failures of different theories of phonology, past and present, shed valuable light on different aspects of the phonologies of languages, which, in turn, may provide insight into reading. In the following, I will discuss three different phonological theories: descriptive linguistics, generative phonology, and articulatory phonology (e.g., Browman & Goldstein, 1986), and discuss the possible insights that an examination of them may provide on reading acquisition and difficulties in learning to read.

Descriptive Linguistics

The aim of descriptive linguists in the domain of phonology was to classify the consonantal and vocalic phonetic segments of the given languages into phonemes. Phonemes are classes of phonetic segments used by members of a language community. Community members use phonemes contrastively to distinguish words; they do not use phonetic segments within a phoneme class contrastively. Examples in English of phoneme classes are /p/, /t/, and /k/. Roughly, each of these phonemes has two variants, an aspirated variant [ph] that occurs in stressed syllable-initial position (pill, till, kill) and an unaspirated version [p] that occurs elsewhere (spill, still, skill). There are no words of English that differ just in whether the unvoiced stop is aspirated or not. So, for example, there is no word [pil] that differs from [phil] in having an unaspirated [p], but otherwise differs in no other way from pill in its form. ([p] differs from the initial segment of bill in having a devoicing gesture.) Thus, the different variants or “allophones” of a phoneme do not contrast. This is different from the relation of either allophone of /p/ relative to /b/. We have word pairs such as pill and bill that differ only in the first consonant and that have different meanings. /p/ and /b/ are contrastive in English.

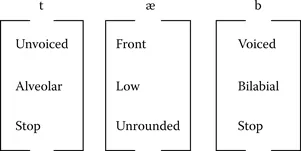

In descriptive linguistics, phonemes are represented in terms of their featural attributes. Figure 1.1 provides an example. In the word tab, the first consonant is an unvoiced, alveolar stop, the vowel is a front, low, unrounded vowel, and the final consonant, /b/, is a voiced bilabial stop consonant. (There are many feature systems. I have chosen a simple one for Figure 1.1.)

Figure 1.1 One way of representing word forms as sequences of consonants and vowels characterized by their featural attributes. The word is tab.

In these representations, consonant and vowel phonemes are discrete from one another and are invariant in their featural attributes. Entities with these characteristics are what the letters of an alphabetic writing system represent more or less directly depending on the writing system.

When consonants and vowels are represented by feature columns, time is absent except as serial order. Therein lies a difficulty for this way of describing phonological or phonetic segments. There are some indications that time is inherent in the consonantal and vocalic segments of languages. For the present, I will present just some of the evidence. Its relevance to reading, however, may not be obvious. After all, alphabetic writing systems have the same character. Time is absent in their representations except as serial order. In the following, I will suggest that the relevance to reading has to do with the attainment of phonemic awareness. It is not always clear whether a set of features constitute one segment or two.

Ewan (1982) offers several examples of the so-called complex segments in which there is ambiguity as to whether a phonological “segment” is really one segment or two. One compelling kind of example comes from languages that will be unfamiliar to most readers. Some languages have consonants that are identified as “prenasalized stops.” These are segments that begin as nasalized segments, but end as oral consonants. An example is from the language Nyanga, the disyllable /mbale/. In this language, prenasalized stops have the duration of single segments. In some languages, they also have the distributional characteristics of single segments. That is, they occur in the contexts that single segments occur in. In Nyanga, they contrast with trisyllabic sequences such as /mbale/ in which the /m/ is syllabic (Herbert, 1977, cited in Ewan).

Although at least one phonologist proposed retaining the featural representation of segments, despite the existence of complex segments, by allowing a feature (here nasality) to change state within a feature column (Anderson, 1976), it violates the fundamental nature of this representation type.

Other examples come from English. English has two affricate consonants, the phone at the beginning and end of the word church and the phone at the beginning and end of judge. Like prenasalized stops, they are characterized by a dynamic change. At onset, they have a stop-like character, but this gives way to a fricativelike character subsequently. Relatedly, two notations are used to represent these phones. In one, they are /ʧ/ and /ʤ/, respectively, whereas in the other they are /č/ and /ǰ/. One segment or two?

A final, surprising set of examples consists of the /s/-stop clusters in English. The clusters /sp/, /st/, and /sk/ appear to be sequences of two consonants. But there are reasons to question whether they are. As consonant sequences they are the only clusters in English that violate the “sonority constraint” that is commonplace in languages. The constraint is that consonants closer to the vowel nucleus in syllables must be more “sonorous” (roughly more vowel-like) than those farther away. So, if /p/ and /r/ precede the vowel in a syllable, the order must be /pr/ (as in pram, for example), with the continuant consonant /r/ closer to the vowel than the noncontinuant /p/. If the same two consonants follow the vowel in a syllable, the order has to be /rp/ (as in harp). But continuant /s/ precedes /p/, /t/, and /k/, both before (spill, still, skill) and after (rasp, last, ask) the vowel. The order violates the sonority constraint before the vowel. But if s-stop “clusters” are, in fact, single segments, then there is no violation. Fudge (1969) points out also that, in English, a statement about what consonants can occur in clusters is simpler (because no three-consonant clusters can occur) if /s/-stop clusters are considered single segments.

I will show shortly that the shortcomings of the featural representations in handling dynamic change can be overcome to a large extent by using a different representational system, that of articulatory phonology (e.g., Browman & Goldstein, 1986, 1992). However, the central message here is not that featural systems are inadequate. It is that word forms are only approximately composed of sequences of discrete consonants and vowels. Some consonants (e.g., prenasalized stops and affricates) and vowels (e.g., diphthongs) have properties of single segments and some properties of sequences of segments. There may be no right answer to the question whether affricates are single segments or else are sequences of segments. They have properties consistent and inconsistent with both solutions.

That is the nature of natural languages. The properties of languages emerge and change as people talk to one another. The properties that work (i.e., that enable communicative exchanges to succeed) have to be mostly systematic, but they do not have to be wholly formal. When phonological analyses fail to capture all of the relevant facts about a language’s phonological system (e.g., when Chomsky and Halle’s (1968) trisyllabic laxing rule has to predict that obesity should be pronounced obehsity), that is just a fact about living languages. There are exceptions to most of the generalizations that can be drawn about the sound systems of language.

What does any of this have to do with reading? For one thing, it offers yet another reason why achieving phonemic awareness is difficult. Phonemic awareness is difficult for children to achieve because, quite rightly, they are inclined to think about what word forms mean, not what they sound like (e.g., Byrne, 1996). If A. M. Liberman (1996) was right that speech perception is served by a brain “module,” then phonemic awareness is also difficult to achieve because language users cannot introspect on the workings of the module (Fodor, 1983) that produces consonants and vowels and extracts them from spoken input. But, thirdly, it is difficult to achi...