eBook - ePub

Urbanisation and Planning in the Third World

Spatial Perceptions and Public Participation

This is a test

- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urbanisation and Planning in the Third World

Spatial Perceptions and Public Participation

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1985, this book reconsiders the whole question of urbanisation and planning in the Third World. It argues that public involvement, which is now an accepted part of Western planning, should be used more in Third World cities. It shows that many inhabitants of Third World cities are migrants from rural areas and have very definite ideas about what the function of the city should be and what it ought to offer; and it goes on to argue that therefore a planning process which involves more public participation would better serve local needs and would do much more to solve problems than the contemporary approach.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Urbanisation and Planning in the Third World by Robert Potter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sociología urbana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

However we choose to define the word ‘urbanisation’, and whether we are inclined to regard it as referring to a primarily economic, demographic or social-behavioural process, there can be little doubting the fact that it signifies one of the most problematical processes confronting mankind in the last two decades of the twentieth century and beyond. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that during the postwar period, a vast literature has developed within the social sciences which specifically seeks to examine the manifold historical, contemporary and prospective aspects of the global trend of urbanisation. This corpus of writing obviously reflects the simple truism that urbanisation involves fundamental shifts and changes in the whole fabric of nations, regions and continents, not least in their social, economic and demographic structuring. Further, it is hard to refute the assertion that along with efforts to alleviate global poverty and hunger, to promote greater equality of opportunity by careful social development, and to enhance world peace and individual security, the tackling of problems associated with rapid urban development will test the ingenuity of mankind to the utmost, and may yet determine the capacity for sustained global development in the future.

The pressing nature of these three major developmental issues of world poverty, peace and human settlements, together with that of rapid total population growth has been clearly exemplified in the document North-South: A Programme for Survival, wherein it is argued that:

There is a real danger that in the year 2000 a large part of the world's population will still be living in poverty. The world may become overpopulated and will certainly be overurbanized. Mass starvation and the dangers of destruction may be growing steadily – if a new major war has not already shaken the foundations of what we call world civilization (Brandt, 1980, p.ll).

Whilst the twin threats of poverty and war are discussed in detail in the Brandt report, the problems posed by ‘overurbanisation’ and human settlements are not fully considered, an omission strongly criticised by many reviewers of the document. This lack of attention is surprising, for at the present juncture, the course of world urban development should hold considerable fascination for all those concerned with global developmental issues. Although historically towns, cities and predominantly urban modes of living have all been synonymous with ‘development’, ‘industrialisation’ and ‘modernisation’, many of the urban areas of the Western world are today increasingly facing problems of atrophy, decay and economic regression in the guise of inner city problems, fiscal bankruptcy and counter-urbanisation (Berry, 1976).

In fact, the problems and challenges afforded by the processes of rapid urban growth and urbanisation are coming increasingly to be associated with the ‘less economically developed’ or ‘poor’ nations of the world, and questions as to whether massive urban agglomerations should be allowed to continue growing or whether decentralisation should be encouraged, what urban form should be envisaged and how the problems of cities can be combated are vexed ones. Thus, the urban containment and decentralisation ideologies which had their origins in Western-industrialised urban systems in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are now increasingly being accepted as the major planning guidelines in many contemporary less developed countries. However, at the same time, views as to the relative social-economic benefits and costs of the growth of large urban agglomerations and urban primacy are far from unequivocal. Similarly, the actual role of cities in the spatial development process is an important, albeit a highly contentious issue. Thereby, the need for sound research and planning is crucial, for even if decanting and spatial dispersion are seen as desirable, the precise configuration of settlements to be promoted and their relative sizes remain as thorny, if not intractable issues. Such topical and fundamental issues underlie the content and orientation of the present volume.

URBAN GEOGRAPHY AND THE THIRD WORLD

The present volume is primarily addressed to students, academics and professionals in the fields of geography, planning and development studies, and is regarded as a contribution to the study of the urban geography of developing nations. This orientation must be stressed for, despite the manifest importance and relevance of the contemporary processes of urbanisation and urban growth in Third World countries, it is true to say that surprisingly few urban geographers have explicitly turned their attentions to them. This is certainly witnessed by the negligible space devoted to the phenomenon of Third World urban development in most student text-books on urban geography, a comment which by and large stands for established classics, as well as recent additions to the literature (Johnson, 1967; Northam, 1979; Hartshorn, 1980; Carter, 1981; Herbert and Thomas, 1982; Clark, D., 1982; Knox, 1982; Short, 1984).

This rather parochial focus of much mainstream urban geography is also exemplified by the content of published research registers covering the field. The Urban Geography Study Group of the Institute of British Geographers (IBG), for instance, compiled a listing of some 227 projects being carried out by its members in 1982. Of these, only ten were classified by the present author as dealing with Third World topics, representing a mere 4.41 per cent of the total. Notwithstanding the fact that geographers who do not profess to work under the prefix ‘urban’ also study urban based topics, the figure is worryingly small. However, of a total of 120 projects listed in the 1982 Research Register of the Developing Areas Study Group of the IBG, again only 19 or 15.82 per cent were on explicitly urban related themes. In fact, it may well be the case that urban geographical interest in Third World urbanisation is at present on the wane rather than the increase. Thus, Warnes (1978) reviewed the contents of an earlier, 1976, IBG Urban Study Group research register and found that 21 or 12 per cent of the total indexed projects were concerned with “urbanization, urban growth”, putting the topic in joint fourth place among members. However, although most of these projects were international or comparative in character, some were entirely Western in focus. Warnes also noted that only 4 projects involved the study of “squatter settlements”. This can be compared with the 1973 Register consisting of 72 projects, where a total of 10, or 21 per cent were on “urbanization, urban growth”, this comprising the first ranking research topic.

This already relatively low and apparently declining level of interest shown in Third World urbanisation can undoubtedly be explained, at least in great part, by changes in the wider economic and academic environments in the post-war period (Farmer, 1983). At the present time of economic recession, and with mounting socio-economic problems in the urban areas of British and other Western countries, it is perhaps inevitable that increasing attention will be given to these pressing domestic issues. However, there is the ever-present danger that this will lead to a form of academic insularity if the interdependent connections existing between global environmental and development problems are ignored, or at best neglected (Brookfield, 1975).

The apparently mounting malaise in Third World urban geographical study can also be viewed historically. The hallmark of human geography in the 1960s was the adoption of an increasingly quantitative approach, an orientation that was closely allied with a commitment on the part of practitioners to theory construction, model building and the search for empirical generalisations. Urban and economic geographers were at the forefront of these developments but their focus was almost exclusively on developed regions and their metropolitan areas. Since the early 1970s, it is fair to say that the topics dealt with by human geographers and the associated methods and philosophies employed have broadened considerably, rendering a buoyant, if not always overtly coherent field of academic teaching and research. An early call in the 1970s was for increasing ‘social relevance’, and an enhanced concern with the potential policy related implications of human geographical research. Another theme has emphasised the importance of the concepts of social justice and social welfare in geographical analyses. Both approaches have given a fresh impetus to urban, economic, social and political geography, but again seem not to have been translated into a direct focus on Third World urban problems.

At the same time, human geographers have been showing a greater interest in political processes as they operate in space from the national to micro-scales. In particular, the provision of welfare and social services has been studied, and again the theme is clearly germane to Third World urban studies, but has largely been pursued in a developed world context. Also, a strong radical approach, often employing Marxist-based ideas has emerged (Peet, 1977), and is reflected in some very significant texts on the general theme of urbanism, particularly those by Harvey (1973) and Castells (1977). A further recent major growth area within human geography has been the study of environmental perceptions and cognitions under the general banner ‘behavioural geography’ (see, for example, Walmsley and Lewis, 1984). This is not to be seen as an entirely new and separate sub-discipline, but rather a fresh paradigm that has been applied in most of the traditional areas of geographical concern. Here too, although much of this work has taken the planning relevance of such an approach as its major theme (Saarinen, 1976; Pocock and Hudson, 1978), and despite some early tentative applications in developing countries (Gould and White, 1974), its full potential has not as yet been assessed in the Third World context.

In summary, therefore, it can be argued that more work has been carried out on Third World urban processes by non-urban geographers and indeed by non-geographers such as sociologists, demographers, historians, economists, social anthropologists and regional scientists than by urban geographers. However, there are some indications that a substantive reorientation is occurring in that human geographers are supplementing their traditional interest in the nature of spatial patterns with a revitalised concern for the aggregate structural and societal processes that give rise to those patterns. Further, there is a current associated trend for the rejection of logical positivism in favour of structuralist, and humanistic approaches such as phenomenology and idealism. As a direct consequence, geography's inter-disciplinary links are becoming more numerous, and in some instances, much stronger. Hopefully, the important topic of Third World urbanisation will thereby receive greater attention in the not too distant future as these methodological ripples spread, and indeed there are already some encouraging signs in this respect (Johnston, 1980; Gilbert and Gugler, 1982; Brunn and Williams, 1983).

SETTLEMENT, PREFERENTIAL, MIGRATORY AND POLICY SPACE IN THIRD WORLD COUNTRIES

The present volume pursues two broad themes. First, it stresses the pressing need for the identification of soundly based and appropriate systems of urban and regional planning in Third World countries, particularly frameworks which explicitly acknowledge the importance of harnessing the aspirations, initiatives and perceptions of individuals and groups, rather than those which are premised on alien models and modes of planning. Secondly, the volume stresses the generally neglected theme that, viewed at one level, the process of rural to urban migration, and the associated phenomena of urbanisation, urban growth and urbanism in Third World countries are the tangible outcome of individuals’ perceptions of environmental and socioeconomic opportunities. Thus, a central argument is that the study of individual and group environmental perceptions stands as a potentially rewarding theme in the analysis of Third World urban and regional patterns; and further, should therefore be regarded as a major potential input into the planning process at the survey, analysis and plan stages (see also Potter, 1983d, 1984b, 1984c).

It may be argued that the principle of public participation in planning is as vital in Third World countries as it is in Western nations, albeit in a somewhat modified form (Franklin, G.H., 1979; Potter, 1984b, 1984c; Conyers, 1982). This is, for example, reflected in the mounting awareness that community-based planning programmes (Kent, 1981) and self-help imperatives must be recognised by Third World planners and politicians, for they express the aspirations and desires of the mass of the populace, and thereby represent a major cultural resource for change. It is all too easy for planners and policy-makers, many of whom have been trained abroad, to assume without question, that tried and tested modes of planning which have proved useful in developed nations will be equally suited to meeting the formidable problems faced by less developed countries (Zetter, 1981).

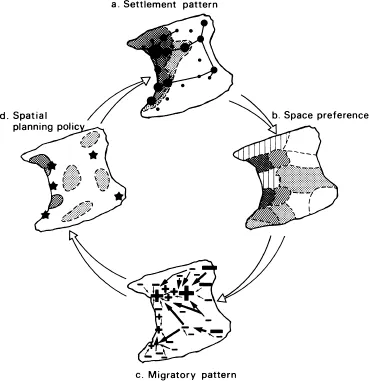

The various strands of this overall argument are developed in the following chapters of this book. It should be stressed that this wider argument concerning the need to open up a genuine and effective dialogue between planners and the planned, applies equally well at both the intra-urban and inter-urban levels. However, as an introductory example, some of the primarily spatial connotations of this suggestion are briefly illustrated here by means of a simple graphical model drawn up at the inter-urban scale (Figure 1.1), and then subsequently by the real world example of Tanzania, also mainly couched at the inter-urban scale.

The urban settlement pattern of a given country or region, that is its configuration of urban places by size and location, is the product of the historical processes of urbanisation and urban growth (Figure 1.1a). It is highly unlikely that urban development will have proceeded evenly and uniformly through space. Typically, certain regions of the national space, in this example the north and western coastal areas, will have become the focus of growth associated with a process of cumulative causation. The corollary will be the lack of development of the peripheral regions, in the example here, the east and south. Decision-makers will inevitably respond to the actual and perceived socio-economic opportunities offered by different localities, that is inter-regional inequalities, so that areas where average wage rates, employment and housing opportunities, medical and social services are believed to be favourable, will be regarded as more desirable than the others. Individuals, corporations, and indeed government organisations and the state itself will all be characterised by their own distinctive national space preference surfaces (Figure 1.1b). Although these will contain many unique elements, it is likely that there will be a generalised or consensus regional patterning.

Figure 1.1: Settlement, preferential, migratory and policy space

However, by definition, space preferences whether individual or corporate are based on past experiences and conditions. Additionally, they are the outcome of far from perfect information gathering and processing abilities. As a consequence, therefore, spatial imagery is likely to show evidence of bias, inertia and misinformation. Thus, space preferences may effectively become stereotypes, showing a poor correspondence with actual environmental conditions. This, of course, is particularly likely if rapid socio-economic change is occurring. For example, labour and capital may continue to migrate toward a particular urban region long after it has reached its social and economic optimum. Similarly, areas of potential growth may remain under-perceived. Some have referred to such disparities between space preferences and actual conditions as constituting a “myth” map.

The present book argues that such perceptions and misperceptions, and the structural circumstances and constraints which underlie them need to be examined and understood if efficacious urban and regional planning is to be promoted in Third World countries. The links existing between settlement patterns and group/individual and institutional space preferences offer valuable insights for planners and environmental policy-makers. The collection of data on environmental perceptions can be regarded as a useful, albeit a specialised method of encouraging public involvement in the planning sequence. Although it must be accepted that spatial migration is basically a structural phenomenon (Lipton, 1980; Thapa and Conway, 1983), these social and economic structures are reflected in individuals’ reasons for spatial migration. Thus, at this level, migration can be regarded as a behavioural response that is based on space preferences, and environmental images of complex socio-economic structures (Wolpert, 1966).

Whether we are talking of direct or step-migration, temporary or permanent moves, there must be a difference in evaluations between the present location and the proposed destination for migration to occur. The only exception to this is in situations where political-military force and coercion are used to move people, unfortunately, a not altogether infrequent situation in developing countries. However, other things being equal, migration occurs from areas of negative or low space preference levels to those of positive or high levels (Figure 1.1c). It can be argued, therefore, that to affect patterns of rural to urban migration, ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Plates

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. THE COURSE OF WORLD URBANISATION

- 3. URBANISATION IN THE THIRD WORLD

- 4. URBAN PLANNING IN THE THIRD WORLD

- 5. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN THIRD WORLD URBAN PLANNING

- 6. PERCEPTION STUDIES AND THIRD WORLD URBAN PLANNING

- 7. CASE STUDIES OF PLANNING RELATED PERCEPTION RESEARCH

- 8. CONCLUSIONS

- Appendix A Barbados Interview Schedule

- Appendix B Trinidad and Tobago Interview Schedule

- Appendix C St Lucia Interview Schedule

- Bibliography

- Index