![]()

Part I

Reducing Supply

![]()

[1]

Evaluating explanations of the Australian ‘heroin shortage’

Louisa Degenhardt1, Peter Reuter2, Linette Collins1 & Wayne Hall1,3

1 National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney NSW, Australia,

2 School of Public Policy and Department of Criminology, University of Maryland, MD, USA

3 Office of Public Policy and Ethics, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD, Australia

ABSTRACT

Aims In this paper we outline and evaluate competing explanations for a heroin shortage that occurred in Australia during 2001 with an abrupt onset at the beginning of 2001.

Methods We evaluated each of the explanations offered for the shortage against evidence from a variety of sources: government reports, police and drug law enforcement documents and briefings, key informant (KI) interviews, indicator data and research data.

Results No similar shortage occurred at the same time in other markets (e.g. Vancouver, Canada or Hong Kong) whose heroin originated in the same countries as Australia’s. The shortage was due most probably to a combination of factors that operated synergistically and sequentially. The heroin market had grown rapidly in the late 1990s, perhaps helped by a decline in drug law enforcement (DLE) in Australia in the early 1990s that facilitated high-level heroin suppliers in Asia to establish large-scale importation heroin networks into Australia. This led to an increase in the availability of heroin, increasingly visible street-based drug markets, increased purity and decreased price of heroin around the country. The Australian heroin market was well established by the late 1990s, but it had a low profit margin with high heroin purity, and a lower price than ever before. The surge in heroin problems led to increased funding of the Australian Federal Police and Customs as part of the National Illicit Drug Strategy in 1998–99, with the result that a number of key individuals and large seizures occurred during 1999–2000, probably increasing the risks of large-scale importation. The combination of low profits and increased success of law enforcement may have reduced the dependability of key suppliers of heroin to Australia at a time when seized heroin was becoming more difficult to replace because of reduced supplies in the Golden Triangle. These factors may have reduced the attractiveness of Australia as a destination for heroin trafficking.

Conclusions The Australian heroin shortage in 2001 was due probably to a combination of factors that included increased effectiveness of law enforcement efforts to disrupt networks bringing large shipments of heroin from traditional source countries, and decreased capacity or willingness of major traffickers to continue large scale shipments to Australia.

Keywords Drug policy drug supply heroin law enforcement supply reduction

INTRODUCTION

Heroin problems in Australia rose substantially in the 1990s [1]. In the largest Australian heroin market, New South Wales (NSW), the price per gram of heroin was at a historic low between 1993 and 1999, purity at ‘street’ level reached 60%, and heroin was the drug most commonly injected by injecting drug users (IDU) [2–4]. Substantial rises occurred in the number of people treated for heroin dependence, heroin-related overdose deaths, heroin arrests and hepatitis C infections [5–7].

A range of factors probably generated this increase. First, heroin availability increased when there was a large population of susceptible youth with limited exposure to heroin, because the preceding wave of initiation to heroin use had occurred a decade before [1]. Secondly, there was a high level of corruption in NSW drug law enforcement in the 1980s and early 1990s [8]. Previous work has suggested that in such instances, corrupt police may choose to restrict the supply of heroin, so as to maintain profits and/or avoid public concern about heroin use [9]; in NSW, there was good evidence to suggest that corrupt specialized drug squads protected existing drug distribution networks and restricted drug supply in NSW [10]. Following the Wood Royal Commission (1994–97), less experienced specialized squads, although willing to investigate such networks, probably lacked the resources (including informants) and expertise to do so [8]. This may have led to increased opportunities for new or expanded organized crime groups to become involved in large-scale heroin importation and/or distribution.

Thirdly, there were changes in the criminal syndicates that imported and distributed heroin in Australia. Southeast (SE) Asian heroin trafficking groups are thought to have targeted the Australian market from 1994 to attain significant market share [8], aided by links with increasingly influential Asian-Australian crime gangs, particularly in key areas in Sydney, namely Haymarket and Cabramatta [11]. This followed the displacement of SE Asian heroin from the US market by Colombian and Mexican sources [12,13]. There also appeared to be a shift in the mode of importation of heroin with increased use of ‘middle men’, or facilitators, based in SE Asia, who connected producers/financiers in SE Asia with importers/distributors in Australia.

Fourthly, there was limited funding for national and international drug law enforcement (DLE) efforts in the early 1990s, in particular for the border and international operations of the Australian Customs Service (ACS) and the Australian Federal Police (AFP) [8]. An increase in supply without a comparable increase in enforcement may have led to ‘enforcement swamping’ [14].

The 2001 heroin shortage

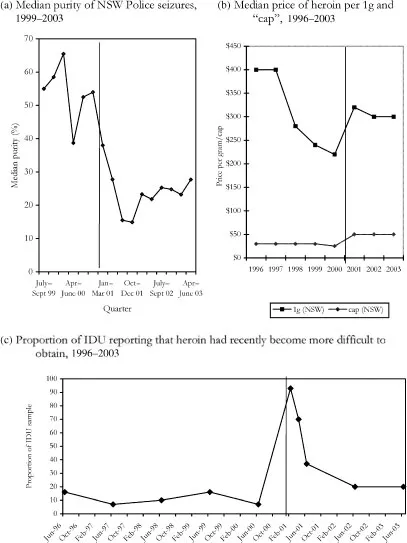

In early 2001, there were reports of a dramatic decline in the availability of heroin in Sydney that marked the abrupt onset of what proved to be a sustained reduction in the availability of heroin, known as the Australian ‘heroin shortage’ or ‘heroin drought’ [12,15–17]. The Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS)—Australia’s strategic early warning system—revealed a similar pattern across Australia, with an overall reduction in the availability and purity of heroin and an increase in heroin price for all major heroin markets (see Fig. 1 for NSW data) [2]; heroin use dropped sharply among IDU, despite continued demand for the drug.

The reduction in availability probably began in January 2001, with peak severity from January-April 2001 [16–18]. IDU reported a median increase of 80 minutes in the time to obtain heroin during January-February 2001 compared to December 2000 [17]. In April 2001, 71 % of IDU interviewed still regarded heroin as more difficult to obtain than December 2000 [19]. Monitoring systems such as the IDRS have indicated that heroin availability, price and purity have not returned to preshortage levels, and as of late 2003, indicators of heroin- related harms remained at much lower levels than before the shortage [20]. Greater detail on the shortage is provided elsewhere [18].

For a number of reasons, it is difficult to make definitive statements about the causes of the shortage. First and foremost, heroin markets are illicit. Even people who are integrally involved lack a detailed or comprehensive picture of the commodity with which they deal [21]. Secondly, illicit drug markets are affected by a multitude of factors that most broadly include supply and demand. Demand can sometimes increase sharply, as during the early phase of an epidemic of use, or it may shift downwards, through increases/improvements in treatment [22]. Downward shifts are less sharp, because dependent users dominate consumption levels, and their use is longlasting and slow to change.

The heroin shortage, however, was clearly an instance of reduced supply, not of reduced demand: users still identified heroin as their primary drug of choice even if they were not using it as often [2,23], and heroin prices rose, which is inconsistent with a fall in demand. It is supply-side factors that we examine in detail in this paper:

• source country conditions: natural conditions; the availability of stable markets for other crops; government action against opium farmers; and traffickers’ changes due to perceived profit changes;

• the intensity and competence of government actions against: drug producers, including precursor control and seizures; source country traffickers; and smugglers;

• changes resulting from law enforcement corruption investigations;

• personnel changes, such as the removal of key figures in drug production or trafficking.

Figure 1 Estimates of heroin price, purity and availability in NSW 1996–2003. (a) Median purity of NSW Police seizures, 1999–2003 (source: Australian Crime Commission), (b) Median price of heroin per I g and ‘cap’, 1996–2003 (source: NSW Illicit Drug Reporting System: IDRS). (c) Proportion of IDU reporting that heroin had recently become more difficult to obtain (source: June estimates IDRS, February 2001 estimate from Day et at. [18], April 2001 estimate from Weatherburn et al. [19])

It is likely that a combination of factors combined to give rise to the reduction in supply of heroin. This paper aims to explore these factors, and reveals the most likely combination of factors that affected the supply of heroin in Australia.

METHOD

Our method was historical and forensic using a modified method of exclusion (Doyle 1892/1983): ‘… when you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however, improbable, must be the truth’ (p. 154) [24]. We listed all hypotheses that had been advanced by researchers, law enforcement officials, drug users, drug policy analysts and the media. These hypotheses were evaluated by their consistency with the information available and their coherence with each other, with the aim of using the available information to exclude the least plausible explanations. As will become clear, because the available information could rarely be used to exclude hypotheses, we compared the plausibility of competing explanations. Our information sources included: government reports, classified police and drug law enforcement documents and briefings, classified briefing documents by Australian agencies, key informant (KI) interviews, examination of indicator data and the use of research data where relevant.

Key informants were chosen strategically, for their knowledge of operations and events prior to 2001, and for their expertise within their organization. All those who were approached agreed to be interviewed for the study. Key informant interviews were conducted at an international level with representatives of the Royal Thai Police (RTP); the Thailand Office of the Narcotics Control Board (ONCB); and Australian Federal Police (AFP) in Thailand. Interviews were conducted in Australia with representatives of the AFP, ACS and NSW Police.

Briefings and discussion documents were also provided by the following Australian law enforcement agencies: the ACS, the AFP, the Office of Strategic Crime Analysis (OSCA) and the Australian Crime Commission (ACC: formerly the National Crime Authority). Security protected documents from NSW Police were also examined, including intelligence reports and reports of the outcome of NSW Police operations.

RESULTS

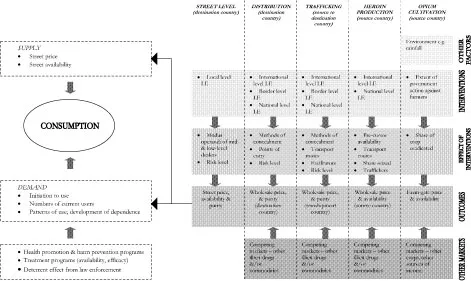

We have classified explanations into factors that may have operated at the level of cultivation/production, international trafficking and Australian distribution. In Fig. 2, the supply chain reads from right to left; changes at any one of these levels can affect supply further along the chain. The movement of key people into and out of the illicit drug trade (at all levels) is motivated by profit margins and influenced by perceived risk (‘interventions’), commodity price (‘outcomes’) and competing markets that potentially provide better profit margins (either because of higher mark-ups or lower risk).

The following example is provided to help illustrate where an effect might be felt, given changes at a particular level. Cultivation levels (far right column) are based on the expectation that a specific portion of crops will not reach maturity: if eradication destroys a larger share of crops than farmers anticipate, a shortage might result. This would continue until traffickers either found new sources of supply or opium farmers adapted by increasing the total land area cultivated or scattered their plants in smaller, less accessible fields. In the interim, prices might rise across the levels of producer, trafficker and distributor, with users competing for a diminished supply (i.e. all columns to the left of the cultivation column would experience the decreased availability and possibly increased price).

Figure 2 Schematic diagram of the factors influencing the trade of illicit drugs

Changes in source country conditions

A popular hypothesis in the media was that the Australian shortage was caused by political changes and weather conditions in the countries in which opium was produced (Fig. 2, cultivation level). This is the least plausible explanation, because these factors would be expected to have affected heroin supply in other countries that receive heroin from the same source, yet Australia was the only country receiving heroin from the Golden Triangle (in contrast to China and Canada) to experience a heroin shortage [8]. ...