eBook - ePub

Global Englishes and Change in English Language Teaching

Attitudes and Impact

This is a test

- 132 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Global Englishes and Change in English Language Teaching analyses the impact of current ELT practice, bringing together research from the fields of Global Englishes and ELT to provide suggestions for the implementation of a Global Englishes for Language Teaching curriculum. Calling for a critical re-examination of ELT to ensure that classroom practice reflects how the English language functions as a lingua franca, this book:

-

- highlights that multilingualism, not monolingualism, is the norm in today's globalised world, and that 'non-native' English speakers far outnumber 'native' English speakers;

- showcases the author's research into English language learner attitudes towards English and ELT in relation to Global Englishes;

- makes practical suggestions for pedagogical change within ELT.

Global Englishes and Change in English Language Teaching is key reading for postgraduate students and researchers in the fields of TESOL/ELT and Global Englishes.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Global Englishes and Change in English Language Teaching by Nicola Galloway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Global Englishes and English language teaching

Nero (2012) summed up the pedagogical implications of the globalisation of English as follows:

The rapid and remarkable shifts in the linguistic tide worldwide over the last quarter of a century have challenged English-language learning and teaching in unprecedented ways. The spread and natural evolution of English itself, combined with the transience in the population of English-language users, have forced a re-examination of the goals of English-language learning and teaching, as well as a reconceptualization of the English language itself, along with sacredly held paradigms in ELT. These changes are likely to continue and to evolve throughout the 21st century, and they will require conceptual and practical flexibility in advancing the field of ELT.

(p. 153)

English as a global lingua franca is used by speakers from diverse lingua-cultural backgrounds; and the spread of the English language has, most certainly, resulted in ‘rapid and remarkable shifts’ (Nero, 2012) in the sociolinguistic landscape. The rapid changes created by globalisation and advances in technology have resulted in English now being used on a daily basis in so-called English as a ‘foreign’ language contexts. Although English may not have an official status in places such as Japan, it has become an integral part of the lives of many citizens. This global ownership of the language raises a number of questions with regard to how it should be taught and learned. With growing research in the field of Global Englishes, there is a need for a ‘reconceptualization of the English language’ (Nero, 2012). Both the needs of students and the goals of ELT have changed, at least for those who will use ELF. However, the prevailing monolingual myth in ELT perpetuates favourable attitudes towards both the idealised construct of ‘native’ English and the ‘native’ English speaking teacher. This chapter examines the pedagogical implications of Global Englishes research, which raises questions regarding which norms to apply, how competence should be defined, who should teach the language and how successful communication is achieved in plurilingual encounters. After examining the proposals that have been put forward, it ends with an overview of the possible constraints, or ‘barriers’, to achieving this much needed paradigm shift. One of these potential ‘barriers’ relates to stake-holders’ attitudes towards the language and the dominance of standard language ideology, a topic explored in depth in Chapter 2.

Global Englishes

English today

Today, English is a language used for diverse communicative purposes in a variety of contexts. It is used as a second, or official, language in many countries and as an official, or de-facto, working language in many international organisations. English is the main language for scientific exchange and has become the main language of academia, international business, political exchange and international diplomacy. It dominates popular culture and international scholarship and is the most widely taught foreign language in the world. In short, it has become the world’s global lingua franca. There are many theories behind the reasons for the global spread of English and, whilst exploration, trade and conquest have, certainly, been significant, language-external factors have been the most influential (see Galloway & Rose, 2015a for an overview of the main developments). The globalisation of English is related to both the political and economic power of the United States at the time when globalisation forces were gathering speed, resulting in an increased demand for a global lingua franca. There is insufficient space here to discuss the history of English and the positives and negatives associated with having a global lingua franca, but it is important to note that English has now spread beyond its original boundaries. It has become a global language, spoken by more ‘non-native’ speakers than ‘native’ speakers. It is, also, now being increasingly used on an internal basis in countries that were traditionally categorised as being English as a ‘Foreign’ Language (EFL) contexts and, as such, it can be said to have a global ownership.

In countries such as Japan, where it does not have an official status, English is being increasingly used on a daily basis in a variety of domains. There are English newspapers and English radio and television programmes. Further, as noted, several companies have implemented English as their official working language and many universities now offer both courses and full degree programmes in English. The global spread of English has not only resulted in an increased demand for English language proficiency, leading to a large number of private language institutions and a lucrative ELT industry, but recent years have also witnessed an increased demand for education through the medium of English, both in Japan and elsewhere. In Europe, for example, there has been a 1,000% rise in English Medium Instruction (EMI) programmes (Brenn-White & Faethe, 2013, p. 6). In Japan, the Japanese government’s Global 30 project aimed to increase the number of foreign students from 14,000 to 300,000 by 2020 (MEXT, 2012, p. 17), and the later Super-, or Top-, Global University Project (TGUP) expanded on this objective, setting a goal of putting 13 Japanese universities in the top 100 world-ranked universities to develop Japan’s globalised higher education profile (MEXT, 2014). In order to achieve this aim, more funding has been made available for universities to develop EMI programmes. Such movements are likely to have a knock-on effect on high school education and, in recent years the age of English instruction has been lowered in primary schools. Such movements also mean increased ELF usage in traditionally monolingual classrooms, thus raising questions about the relevance of the ‘native’ English speaker model in Japanese ELT.

Whilst the numbers of English speakers today may be difficult to estimate, due to problems associated with measuring proficiency, the fact that ‘non-native’ English speakers now outnumber ‘native’ speakers of the language has resulted in a shift in ownership as well as use. The diverse use of English around the globe in different domains and contexts has given rise to distinct research paradigms that focus on how it is used, what it looks like, how it is appropriated to adapt to local contexts and communicative needs, how it functions as a lingua franca in multilingual contexts, and how it should be taught to reflect such global usage. These research paradigms are discussed next.

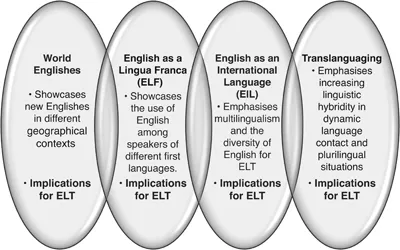

Global Englishes research

Studies positioned within the fields of World Englishes (c.f. Kachru, Kachru, & Nelson, 2006), ELF (c.f. Jenkins et al., 2011; Seidlhofer, 2011), EIL (c.f. Alsagoff et al., 2012; Matsuda, 2012; McKay & Brown, 2016) and Translanguaging (c.f. Canagarajah, 2013a; Garcia, 2009) showcase how the language functions today, highlighting the pluricentricity of English, its global ownership and how it is very different to the ‘native’ form taught in the ELT classroom. Researchers in all of these fields have questioned the relevance of such norms for ELT in light of their research findings. Notwithstanding their different stances, such work has a similar underlying ideology, united in the desire to showcase the diversity of English and to instigate a paradigm shift in ELT. As such, they form part of the broader paradigm of Global Englishes (Figure 1.1). The Centre for Global Englishes at The University of Southampton states on its website that it

Figure 1.1 The Global Englishes paradigm

produces and disseminates research on the linguistic and sociocultural dimensions of global uses and users of English (Global Englishes) and on English as a Lingua Franca, in particular.

(‘Centre for Global Englishes | University of Southampton,’ n.d.).

Widdowson (2012, p. 22) places ELF within the Global Englishes paradigm and Galloway and Rose (2015a) also include these linguistic and sociocultural dimensions, putting forward the following definition,

a paradigm that includes the concepts of World Englishes, ELF and EIL and examines the global consequences of English’s use as a world language. In many ways, the scope of Global Englishes extends the lenses of WE and ELF to incorporate many peripheral issues associated with the global use of English, such as globalisation, linguistic imperialism, education, language policy and planning.

(Galloway & Rose, 2015a, p. 254)

They also note that this resonates, in many ways, with Canagarajah’s (2013b) notion of ‘translingual practice’ (Canagarajah’s, 2013b, p. xiv), given the focus on the increasing linguistic hybridity and use of negotiation strategies to achieve successful communication. This book adopts this definition of Global Englishes as an umbrella term, yet as noted in the preface, uses translanguaging as a further umbrella term, including work on translingual practice and related fields such as plurilingualism. Global Englishes aims to bring these fields together to showcase the increasing body of research on how the English language functions as a global language. World Englishes research has been instrumental in raising awareness of the diversity of English use around the world and the various implications the existence of ‘Englishes’ has for ELT, and it is important to acknowledge this significant contribution. However, globalisation and increased ELF usage in fluid and dynamic contexts has made it increasingly difficult to neatly label ‘varieties’ of English, or even languages for that matter. Both ELF and work on translanguaging showcase how users of ELF uti-lise their integrated proficiency, as they negotiate communication in plurilingual encounters. EIL scholars, who mostly focus on the pedagogical implications of the global spread of English, have also made an important contribution to the field. However, as noted in the preface to this book, misunderstandings of the nature of ELF research are also acknowledged (Galloway & Rose, 2015a).

World Englishes

The term ‘World Englishes’ was first proposed in the 1970s by Braj Kachru and Larry Smith. Kachru’s (1992, pp. 356–357) three-circle model was ground-breaking, pluralising the language and showcasing how English functions in different contexts around the globe. Because of such work, it has now become quite common to talk of English in the plural form to capture the sociolinguistic reality of the language. This pioneering research on the various Englishes around the world showcases the multiplicity and complex nature of English as a global language. The three-circle model positions the English language in terms of three concentric circles. In the Inner Circle it functions as a ‘native’ language, in the Outer Circle as a second language in former colonies, and in the Expanding Circle, as a ‘foreign’ language, where it has no official status. Work has mostly been conducted on documenting the distinctive features of these Englishes, mostly in the outer circle, showcasing how they are influenced by the speakers’ first language and, also, how they differ to ‘native’ English. Such work on codifying these Englishes, and showing how unique features are systematic, with locally appropriate functions, was viewed as being an important way to legitimise them. Kachru (1992) referred to Englishes in the Inner Circle as ‘norm-providing’, those in the Outer Circle as ‘norm-developing’, as they have their ‘own local histories, literary traditional pragmatic contexts and communicative norms’ (Kachru, 1992, p. 359), and those in the Expanding Circle, such as Japan where they are taught as a ‘foreign’ language as ‘norm-dependent’. The implications of such research for ELT has been discussed at length within the field. Warschauer (2000), for example, noted that,

The growing prominence of regional and local varieties of English has several implications for English teaching in the 21st century… First, English teachers will need to reconceptualise how they conceive of the link between language and culture.

(p. 514)

Kachru (1985) advocated adopting a ‘polymodel’ approach to ELT, to expose students to different Englishes, rather than just one ‘native’ variety. The aim was to raise their awareness of diversity and improve their confidence as speakers of their own legitimate variety. However, as Y. Kachru (2005) warned,

[W]orld Englishes means making learners aware of the rich variation that exists in English around the world at an appropriate point in their language education in all three Circles and giving them the tools to educate themselves further about using their English for effective communication across varieties.

(p. 166)

The key aim, therefore, is to raise students’ awareness of the diversity of English, not expose them to every regional variety of the language. However, with increased globalisation, communication in English increasingly takes place both within and across all three circles as a lingua franca, where users of the language have to negotiate ‘effective communication across varieties’ (Kachru, Y. 2005). It now seems to be generally accepted that students do need to be made ‘aware of the rich variation that exists in English’ (Kachru, Y. 2005) and, indeed, many ELT course book writers have responded to this with token examples of ‘non-native’ English on accompanying audio or short reading passages exploring variation in the English language (see Galloway, 2018 for a discussion of ELT materials). However, the tools required for ELF make this three-circle model now appear rather out-dated. The model has certainly helped legitimise these Englishes for particular communities, but they now often have relevance beyond their original boundaries (Canagarajah, 2013a). Indian English, for example, is used in call centres in the Outer Circle that cater for callers from countries placed in the Inner Circle, and this variety of English is also relevant for those conducting business in India. The use of English by more ‘non-native’ English speakers than ‘native’ speakers also brings into question ‘the ‘periphery’ status of the outer and expanding circles in the Kachruvian model’ (Canagarajah, 2013a, p. 4). It is clear from the discussion at the start of this chapter that in places like Japan it is questionable how they can be considered to be ‘norm dependent’ (Kachru, 1992), given the growing use of English internally. Thus, World Englishes, and the associated three-circle model, is to be commended for focusing scholarly attention on the diversity of English and legitimising different Englishes as varieties of the language in their own right with relatively stable features in the societies in which they are used. However, increased globalisation has called for further examination of how the English l...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- 1 Global Englishes and English language teaching

- 2 English language attitudes

- 3 Language attitudes, pedagogy and Global Englishes: An empirical study

- 4 GELT in practice

- Appendix A: Lesson plans and activities

- Appendix B: Participant profiles

- References

- Index