![]() Part 1

Part 1

The Why, How, and Consequences of Agricultural Policies![]()

1

The United States

BRUCE L. GARDNER

Origin and Evolution of U.S. Farm Policies

The U.S. government has been intervening in agricultural commodity markets for more than fifty years. Much experimentation has occurred, but the policies in place in the 1980s were similar to those of the 1930s. Both decades started with government-controlled commodity stock accumulation and soon moved into acreage controls induced by payments to producers as surplus production persisted. However, payments were larger in the 1980s than in the 1930s, and the percentage of cropland idled was the largest in history. The 1980s differed in more fundamental ways also, because of the greatly changed macroeconomic and international environments.

This chapter assesses the U.S. experience in protecting agriculture, emphasizing events of the 1980s and proposing where policy might go in the future. It first reviews past U.S. agricultural policies, then analyzes current programs, and finally discusses options for both the short run and the long run.

Objectives of Agricultural Policy

Why is agriculture protected? Among the many reasons given, the following seem most prevalent:

- to cushion farmers' incomes against adverse economic developments;

- to provide a more stable economic environment in which risky but productive investments in agriculture are fostered;

- to promote food security;

- to preserve the traditional system of family farming;

- to foster conservation of productive farmland by protecting it against erosion and other natural hazards and by preventing conversion of prime cropland to nonfarm uses.

Farm income support was clearly the top priority during the depression of the 1930s, and it was again in the 1980s. The New Deal wanted first and foremost to get increased purchasing power in the hands of rural people. In the 1980s, the primary force moving the now overwhelmingly urban electorate to support agriculture was the perception that a great many farms are, through no fault of their own, on the verge of bankruptcy. On the other hand, economists have emphasized economic stability. Kenneth Boulding (1983) puts the point as follows: "The uncertainty involved in meaningless market fluctuations discourages innovations and investment and limits our getting richer. This is a point too much neglected by economists, as the remarkable history of American agriculture since price supports should have shown."

In the United States, the threat of food shortages is not so strong a political force as it seems to be in Japan and other food-importing countries, but food security is a concern nonetheless. In the mid-1970s, consumer interests for a time even overrode those of farmers when the two conflicted. In more normal times there is a perception that an economically healthy agriculture is a kind of food-supply insurance for consumers, and this contributes to support for protection of agriculture.

The virtues of an economic organization of agriculture in which family farms predominate are regularly invoked in farm policy debates, but the idea of a family farm is hazy. It is clear that farming corporations that hire professional managers, issue stock, and distribute profits to people who do not live on farms are not family farms. Neither are "hobby" farms, on which a person with mostly off-farm income raises a couple of horses and grows hay. But the precise line is difficult to define. Newspaper stories such as an article in the Washington Post detailing how the crown prince of Liechtenstein's Texas farm received $2.2 million in farm program payments convey strong antiprotection sentiment. The objective of farm policy is not seen as providing aid to this type of farm.

The pursuit of these objectives can be complicated and is often indirect. Sending cash to farmers is not the usual way to support farm income. Instead, steps are taken either to increase farmers' receipts or decrease their costs. Costs are seldom reduced directly by input subsidies (such as the fertilizer subsidies that exist in many countries). Rather, indirect subsidies are more common, the most important being governmental provision of research, extension, and technical education in agriculture. Farmers may also receive subsidized crop insurance, electric power, credit, and exemption from environmental and minimum wage regulation.

Generally, the role of government in these areas has been seen by historians as benign. A fairly typical view is that expressed by Schlesinger (1984):

No sector of the economy has received more systematic government attention, more technical assistance, more subsidy for research and development, more public investment in education, in energy supply, and in infrastructure, more price stabilization, more export promotion, more credit and mortgage relief. National planning thus transformed a weak, disorganized and poverty-prone sector of the economy into America's most spectacular productive success.

Such broad consequences of policies are difficult to assess. This chapter concentrates on the aspect of agricultural protection that focuses on the commodity markets. U.S. farm policy since the 1930s has been aimed at protecting farmers' market receipts. This is achieved by supporting prices received by farmers, either by boosting market prices or by payments to farmers to supplement their market receipts, or both.

Evolution of Farm Policies and Farming

Over the past fifty years, U.S. farm policy has provided support for major commodities such as wheat, feed grain, cotton, and dairy products. Commodities such as sugar, rice, peanuts, tobacco, and wool have also received support and protection. But several other important commodities, including hogs, poultry, soybeans, and many vegetables, have not received significant protection.

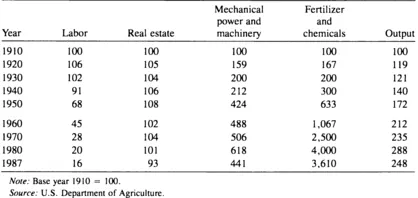

Table 1-1 shows the historical record of the main indicators of intervention in commodity markets. The programs of the 1930s were viewed as massive interventions at the time but were dwarfed in the 1960s and again in the 1980s. During the past fifty years, the number of U.S. farms fell from about 6.5 million to 2.2 million, a trend rate of about 2 percent annually. This suggests a declining sector, but while labor used in agriculture has fallen sharply, other inputs have increased and land in crops has been about constant. Indexes of input and output quantities are given in table 1-2. Increased investment and total factor productivity rising at a trend rate of 2 percent annually since 1940 indicate a quite dynamic sector. And as the number of farmers has declined, the standard of living of rural people has improved. Income per capita has grown faster among farm families than in the United States as a whole. An outline of the program chronologies is given in table 1-3.

The problem in the 1980s was the large buildup of commodity stocks that resulted from the weakening of the strong export markets of the 1970s. As support prices continued to maintain farmers' production incentives, federal outlays increased for deficiency payments, diversion payments, and Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) purchases and loans between 1980 and 1986 (table 1-4).

Table 1-1. Historical Record of Main Indicators of Intervention in Agriculture, 1933-1987

| | | Government payments to farmers |

| Year | Diverted acres (millions) | Government stocks (millions of 1967 dollars)a | (millions of 1967 dollars)a | (1967 dollars per farm) |

| 1933 | 0 | 0 | 337 | 50 |

| 1934 | 35 | 0 | 1,112 | 164 |

| 1935 | 30 | 0 | 1,394 | 204 |

| 1936 | 31 | 0 | 669 | 99 |

| 1937 | 26 | 0 | 781 | 117 |

| 1938 | 0 | 21 | 1,056 | 161 |

| 1939 | 0 | 26 | 1,834 | 284 |

| 1940 | 0 | 1,126 | 1,721 | 282 |

| 1941 | 0 | 1,646 | 1,233 | 196 |

| 1942 | 0 | 1,389 | 1,331 | 214 |

| 1943 | 0 | 1,729 | 1,245 | 204 |

| 1944 | 0 | 1,633 | 1,472 | 245 |

| 1945 | 0 | 1,710 | 1,376 | 234 |

| 1946 | 0 | 837 | 1,319 | 222 |

| 1947 | 0 | 439 | 469 | 79 |

| 1948 | 0 | 208 | 356 | 61 |

| 1949 | 0 | 1,515 | 259 | 45 |

| 1950 | 0 | 3,639 | 392 | 72 |

| 1951 | 0 | 1,841 | 367 | 67 |

| 1952 | 0 | 1,349 | 345 | 66 |

| 1953 | 0 | 2,694 | 265 | 53 |

| 1954 | 0 | 4,260 | 319 | 66 |

| 1955 | 0 | 5,700 | 285 | 61 |

| 1956 | 14 | 6,614 | 680 | 150 |

| 1957 | 28 | 5,620 | 1,205 | 275 |

| 1958 | 27 | 5,430 | 1,257 | 297 |

| 1959 | 22 | 6,024 | 781 | 210 |

| 1960 | 28 | 6,788 | 791 | 199 |

| 1961 | 53 | 6,208 | 1,666 | 436 |

| 1962 | 64 | 4,938 | 1,928 | 523 |

| 1963 | 56 | 5,153 | 1,849 | 517 |

| 1964 | 55 | 4,963 | 2,347 | 743 |

| 1965 | 57 | 4,349 | 2,606 | 776 |

| 1966 | 63 | 2,407 | 3,371 | 1,035 |

| 1967 | 40 | 1,005 | 3,079 | 973 |

| 1968 | 49 | 1,021 | 3,322 | 1,081 |

| 1969 | 58 | 1,624 | 3,455 | 1,265 |

| 1970 | 57 | 1,370 | 3,196 | 1,081 |

| 1971 | 37 | 921 | 2,592 | 893 |

| 1972 | 62 | 662 | 3,161 | 1,105 |

| 1973 | 19 | 296 | 1,958 | 693 |

| 1974 | 3 | 127 | 359 | 128 |

| 1975 | 2 | 249 | 500 | 187 |

| 1976 | 2 | 371 | 430 | 157 |

| 1977 | 0 | 608 | 1,002 | 370 |

| 1978 | 16 | 606 | 1,550 | 580 |

| 1979 | 11 | 570 | 647 | 271 |

| 1980 | 0 | 1,134 | 515 | 218 |

| 1981 | 0 | 1,387 | 709 | 301 |

| 1982 | 11 | 1,905 | 1,208 | 516 |

| 1983 | 78 | 3,551 | 3,115 | 1,331 |

| 1984 | 27 | 2,443 | 2,711 | 1,164 |

| 1985 | 34 | 2,662 | 2,400 | 1,050 |

| 1986 | 49 | 3,500 | 3,598 | 1,400 |

| 1987 | 60 | 2,847 | 4,912 | 2,340 |

Table 1-2. Index of U.S. Farm Inputs and Output, 1910-1987

Farm Income. Although farm policies have remained similar in approach throughout the past fifty-five years, the economics of farming has changed considerably. In particular, the markets for farm resources have become better integrated with the nonfarm economy. This point is especially important for human resources in agriculture. The "farm problem" of the 1930s and 1950s was excess labor in agriculture. With better integration of farm and nonfarm

Table 1-3. Outline of Commodity Program Chronologies

| Commodity | Program |

| Corn | Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933 introduced payments for idled acreage. |

| AAA of 1938 introduced marketing quotas. |

| Marketing quotas ended in World War II; acreage allotments continued after 1948. |

| Agriculture Act of 1956 established “soil bank” payments for idled acreage. |

| Feed Grain Act of 1963 introduced payments on allotment-based output. |

| Food and Agriculture Act of 1977 introduced target price payments, extended to 1990 in the Food Security Act of 1985. |

| Agriculture and Food Act of 1981 authorized 1983 Payment-in-Kind (PIK) program. |

| Food Security Act of 1985 cut Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) loan rates. |

| Wheat | AAA of 1933 introduced payments for idled acreage and also payments for production on “allotment” acreage. AAA of 1938 introduced marketing quotas. |

| P.L. 480 of 1954 subsidized exports (also authorized by AAA amendments of 1935). |

| Agriculture Act of 1964 eliminated marketing quotas, which had been rejected by a producer referendum, and substituted payments for diverting acreage and payments on part of each producer's base output allotment. |

| Food and Agriculture Act of 1977 abolished allotments and introduced subsidy payments proportional to production, and retained payments for diverted acreage. |

| Food Security Act of 1985 based payments on past production, cut loan rates, and mandated use of CCC stocks in export promotion. |

| Soybeans | No acreage controls or subsidies; except on vegetable oils in World War II. Low-level CCC loan rates, effective sporadically. |

| Rice | In 1935, payments introduced for acreage reduction under the AAA. |

| AAA of 1938 introduced marketing quotas. |

| P.L. 480 of 1954 subsidized exports. |

| Rice Production Act of 1975 eliminated marketing quotas and introduced subsidy payments on base output. |

| Food Security Act of 1985 eliminated effective CCC price support but continued payments. Acreage controls continued. |

| Cotton | AAA of 1933 introduced payments for idled and plowed-up acreage, and supplemental payments on products sold. |

| Bankhead Act of 1934 introduced constraints on quantity marketed. |

| CCC export subsidy program was introduced in 1956. |

| Agriculture Act of 1964 introduced subsidy payments to domestic cotton mills. |

| Marketing quotas ceased in 1970 and payments for idling land and subsidies on the allotment base were introduced. |

...