eBook - ePub

The Evolving Arab City

Tradition, Modernity and Urban Development

This is a test

- 314 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Evolving Arab City

Tradition, Modernity and Urban Development

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Today cities of the Arab world are subject to many of the same problems as other world cities, yet too often they are ignored in studies of urbanisation.

This collectionreveals the contrasts and similarities between older, traditional Arab cities and the newer oil-stimulated cities of the Gulf in their search for development and a place in the world order. Theeight cities which form the core of the book – Rabat, Amman, Beirut, Kuwait, Manama, Doha, Abu Dhabi and Riyadh – provide a unique insight into today's Middle Eastern city.

Winner of The International Planning History Society (IPHS) Book Prize.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Evolving Arab City by Yasser Elsheshtawy, Yasser Elsheshtawy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arquitectura & Arquitectura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Great Divide: Struggling and Emerging Cities in the Arab World

Yasser Elsheshtawy

- The Minaret wept

When a stranger came – bought it

And built on top of it a chimney

Adonis, The Minaret

The Weeping Minaret

Do Arabs still exist? Not in the sense of a physical presence – but rather as a vital and contributing civilization. The great Arab poet Adonis argues the following:

If I look at the Arabs, with all their resources and great capacities, and I compare what they have achieved over the past century with what others have achieved in that period, I would have to say that we Arabs are in a phase of extinction, in the sense that we have no creative presence in the world… We have become extinct. We have the quantity. We have the masses of people, but a people becomes extinct when it no longer has a creative capacity, and the capacity to change its world. 1

He reflects a sense of doom and hopelessness. In his poem ‘The weeping minaret’ he elaborates on the role of the ‘stranger’ – the colonialists, multi-national corporations, occupying forces – and the degree to which they have subverted symbols of Arab identity – signified here by the minaret – and replaced them with signs of Western power, i.e. the ‘chimney’ (figure 1.1). In other words while much of the blame for the Arab crisis is from within, external forces are conspiring to maintain the region in a constant state of backwardness. Some Western observers went so far as calling the Middle East ‘the middle of nowhere’.2

These are certainly popular sentiments for many in the region. There are many indicators that would indeed suggest that this is the case – that the Arabs are simply not contributing in any substantive way to science, literature and the arts. Rather, they are recipients, consumers, and proponents of extremist ideologies. For instance a recent UN report estimates that the number of books published in the Arab world does not exceed 1.1 per cent of world production even though Arabs constitute 5 per cent of the world population. This number becomes even more alarming if we consider that the majority of these books are of a religious nature (Arab Human Development Report, 2003).3 There is a growing conservatism sweeping the Arab world, even in formerly liberal and cosmopolitan cities such as Cairo, in a way responding to this perceived ‘threat’ by turning inward and adapting religious symbols such as the veil, which some scholars have called ‘medieval modernity’ (AlSayyad, 2006).

Figure 1.1. The minaret of the Farag ibn Barquq Mosque in Cairo enveloped by informal settlements built in proximity to the City of the Dead.

How is this related to cities? In looking at cities in the region one certainly cannot escape this sense of doom either: whether it is the dismantling of Baghdad; the bombing of Beirut; or the grinding poverty in the slums of Cairo and Rabat – all highlight the critical situation facing our urban conglomerates. They have become sites of struggle and contestation, spaces of doom rather than spaces of hope. Contrast this with the glitz and glamour of Dubai or Doha – centres that have become a model for the Arab world. By opening up to global capital they have the potential to become a ‘new Arab metropolis’ to use Fuad Malkawi’s title in his prologue here – adapting Western forms and planning models. Unburdened by history they are free to create a new identity and in turn serve as a model for the rest of the Arab world. Perhaps they have become the new ‘stranger’ to paraphrase Adonis. This book provides a glimpse into a select set of Arab cities where these issues are addressed from a variety of perspectives. It should be left to the reader to decide on the accuracy of Adonis’s assessment of the Arab condition.

The Arab City: Definition and the Book’s Approach

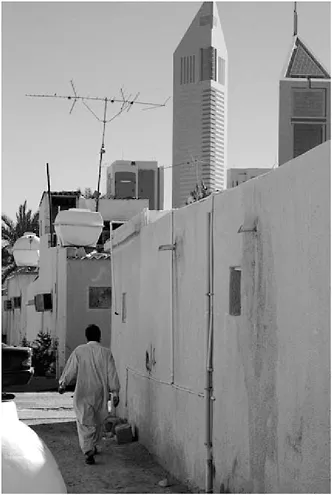

The word ‘Arab City’ evokes a multitude of images, preconceptions and stereotypes. At its most elementary it is for many a place filled with mosques and minarets; settings characterized by chaotic, slum-like developments; a haven for terrorists; maze-like alleyways; crowded coffeehouses where people sit idling their time away smoking a nerghile; sensuality hidden behind veils and mashrabiy’yas. But it is also a place of unprecedented development, rising skyscrapers, modern shopping malls, unabashed consumerism. Most importantly it is a setting where one can observe the tensions of modernity and tradition; religiosity and secularism; exhibitionism and veiling; in short a place of contradictions and paradoxes. Each of these characterizations plays into clichés about what constitutes an Arab or Middle Eastern city. The latter term is particularly problematic – being primarily a British colonial invention – indicating the location of ‘this’ region in relation to both Britain and India. Furthermore, it excludes cities of North Africa. It may be more accurate to describe them as Arab cities. But here again, one may object that such depictions are conducive to more stereotyping. At the same time, arguments are made that there is a divide in this region between newly emerging cities (the Gulf) and the traditional centres – a form of ‘gulfication’ or ‘dubaization’ in which these new centres are influencing and shaping the urban form of ‘traditional’ cities. Counter arguments are made that cities in the Middle East and North Africa are influenced by a variety of cities and regions throughout the world and that the relationship is far more complex than a one-way, linear directionality (figures 1.2a and b).

Figure 1.2a. The decay of Cairo – Manshiet Nasser informal settlement in Cairo (the garbage collectors district).

Figure 1.2b. The glamour of Dubai – the Madinat Jumeirah Complex and the Burj Al-Arab Hotel.

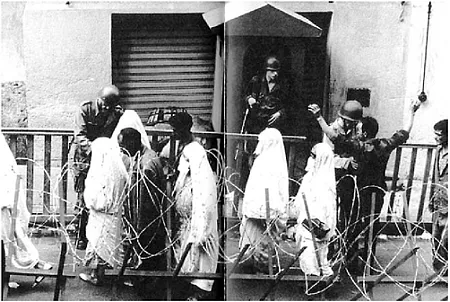

The Arab/Middle Eastern city is thus caught between a variety of worlds, ideologies, and struggles. At its very essence it is a struggle for modernity and trying to ascertain one’s place in the twenty-first century. The paradoxes described above are remnants of the past: of the colonial heritage which did, and still does, play a large role in determining the region’s direction. It could thus be argued that colonialism has returned – in a more subtle and disguised form – and in some instances instigated by local elements. In the movie The Battle of Algiers by Gillo Pontecorvo the city’s traditional quarter, the qasbah, the site of resistance, is contrasted with the European quarter, the seat of the colonial masters. In order to deal with the insurgency, the qasbah is sealed and movement between the two worlds is strictly controlled (figure 1.3). While the colonials eventually left, the divide essentially remained. As a consequence the region was mired for a long time in struggles and conflicts, depriving it of the ability to develop properly. The qasbah’s scope simply grew to encompass the whole region. Now in the current climate of globalization and the growing influence of multi-national corporations, the ‘West’ has returned – yet these developments tend to be exclusive, catering to an elite segment of society – both local and foreign. The majority of locals are kept out – thus the qasbah phenomenon has returned but in a more refined and subtle manner. Yet, is this a phenomenon reserved for the formerly colonized only? Or, should this be understood in the wider context of globalization?

Figure 1.3. Film still from The Battle of Algiers. The entry to the qasbah is controlled by French soldiers.

Many of these issues tie in with global city theory. For example the notion of exclusion is being presented as a characteristic of world cities which has been thoroughly discussed by John Friedmann and Goetz Wolff, Saskia Sassen, Peter Marcuse and others (Friedmann and Wolff, 1982; Marcuse and Van Kempen, 2000; Sassen, 2001). Furthermore, an essential component of world cities discourse is the construct of networking. Cities are conceived as lying on a network, and research is directed at ascertaining the level of connectivity – a space of flows as opposed to the space of places as developed by Manuel Castells (1996). More recent research by Sassen (2002) as well as Stephen Graham and Simon Marvin (2001) discussing the impact of network infrastructures on city form tends to affirm the connectivity among cities and the fragmentary nature of contemporary urban structures. Recently a number of critics have pointed out that the typical global city discourse has left out many cities; they are ‘off the map’ and increasingly have been calling for an examination of ‘marginalized’ cities. A central construct underlying these new developments is the notion of transnational urbanism in which urbanizing processes are examined from ‘below’, looking at the lives of migrants, for example, and the extent to which they moderate globalizing processes (Robinson, 2002; Peter-Smith, 2001). The global city discourse – whereby certain cities are offered as a model to which other cities must aspire to if they are to emerge from ‘off the map’ – is essentially in dispute. Underlying all these critiques is the work of urban sociologist Janet Abu-Lughod (1999) who has written extensively on Middle Eastern cities and has reminded us that globalization needs to be placed in its proper historical context (figures 1.4 and 1.5).

Cities in the Arab world are curiously left behind in this discussion. A cursory look at the literature reveals that since the publication of the earlier Middle East cities volume (Elsheshtawy, 2004a) there have been hardly any attempts to address the state of the contemporary Arab city. Exceptions exist such as Diane Singerman and Paul Ammar’s collection on Cairo (Singerman and Ammar, 2006) forcefully arguing for the emergence of a ‘new Middle East’. Another interesting collection dealing with the historical development of Cairo is by Nezar Al Sayyad, Irene Bierman and Nasser Rabat, all scholars residing in the US and forming what is called the Misr Research Group. The aim of their book is to present the case of medieval Cairo using a transnationalist perspective. While clearly geared towards historians it has value for contemporary scholarship as well (AlSayyad, Bierman and Rabbat, 2005).

Another interesting collection of chapters addressing developments in the city of Dubai from a critical perspective is by anthropologist Ahmed Kanna (2008).

Figure 1.4. Shanghai: a ‘globalizing’ city. City residents rest opposite an upscale shopping centre in the city’s central district.

Figure 1.5. Social exclusion. The Satwa district in Dubai; the Emirates Towers on Sheikh Zayed Road appear in the background.

These chapters are unique in that they tie together a variety of perspectives – sociological, political, architectural, historical, etc. In that way the multi-dimensional nature of Arab cities is exposed and it is shown that they are plagued with many problems similar to other world cities and as such can make a positive contribution to understanding urbanizing processes in the twenty-first century. They are not a one-thousand-and-one night’s fantasy relegated to studying issues of heritage, identity and Islamic urbanism. It is however a sad reflection on the state of Arab scholarship that no other books or substantive studies have been published in the intervening years.4

One of the aims of the present book is to enrich the study of urbanism and of globalizing processes, building on the previously mentioned studies, and at the same time to provide an accompaniment of sorts to the earlier book, Planning Middle Eastern Cities (Elsheshtawy, 2004a). Within this context the contributors were invited to reflect on the urban development of their respective cities from the nineteenth century to the present day. This particular time-frame was chosen to illustrate the impact of colonialism (or foreign protection) on the cities’ morphology and to draw parallels (or differences) to the current discourse on globalization.

Like the first book, the eight authors here are all affiliated with their cities, either as long time residents, or having lived in the city for some time in the past. Further, the aim of both books is to introduce to a wider global audience a new generation of Arab researchers. With one exception, all the contributors teach and practise within the Middle East. Their backgrounds are primarily architectural but there are exceptions: Mustapha ben Hamouche (Manama) comes from a planning background; Sofia Shwayri from archaeology and Jamila Bargach is trained as an anthropologist. This diversity broadens the scope and perspective of the book.

I posed the following questions to the authors as a starting point for reflection on their respective cities:

- ♦ How did the city’s encounter with modernity (whether through colonialism or globalization) shape and influence its urban form and built environment?

- ♦ What influences are Middle Eastern cities subjected to?

- ♦ How are Middle Eastern cities placed within the global city discourse?

- ♦ What efforts are being made to integrate with other world cities? Is national identity being subordinated in favour of ‘global urbanism’?

- ♦ To what extent are policies of exclusion used to marginalize the lower strata of society?

- ♦ What images are being projected by the cities in their drive to modernize?

- ♦ To what extent is the ‘local’ utilized in projecting such images?

- ♦ To what extent does the post-colonial condition of some Middle Eastern cities relate to their colonial history? Is there any relationship between post-colonialism and modernity?

I also encouraged contributors to situate and complement their depictions with case studies that would exemplify the transformations which have occurred. In structuring this book I have used both a geographical and a socio-cultural marker in grouping them. Thus the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Illustration Credits and Sources

- The Contributors

- 1 The Great Divide: Struggling and Emerging Cities in the Arab World

- 2 The New Arab Metropolis: A New Research Agenda

- 3 Amman: Disguised Genealogy and Recent Urban Restructuring and Neoliberal Threats

- 4 From Regional Node to Backwater and Back to Uncertainty: Beirut, 1943–2006

- 5 Rabat: From Capital to Global Metropolis Jamila Bargach

- 6 Riyadh: A City of ‘Institutional’ Architecture

- 7 Kuwait: Learning from a Globalized City

- 8 Manama: The Metamorphosis of a Gulf City

- 9 Rediscovering the Island: Doha’s Urbanity from Pearls to Spectacle

- 10 Cities of Sand and Fog: Abu Dhabi’s Arrival on the Global Scene