1

Maritime Ports and the Politics of Reconnection

Peter V. Hall and Anthony Clark1

Half a century of change in ports, shipping, and trade has profoundly reshaped relationships between ports and their cities. The concept of disconnection has been used to describe the process whereby once tight physical, economic, and institutional relationships between general cargo ports and their cities have changed with the introduction of containerization and other shipping innovations (Hall 2007). Disconnection has had profoundly negative consequences for city-regions containing ports; as the (private) benefits of increased cargo throughput have become more widely dispersed geographically, the (social) costs are concentrated locally (Hesse 2006; McCalla 1999). The simultaneous spatial concentration and dispersal of port-related activity shares much with the processes of global city formation that Sassen (1991) and others have related to the changing spatial organization of finance and advanced business services.

For port cities, the critical analysis of these scholars describes a period in which ‘flow’ has dominated ‘fixity’, when carriers and shippers have enjoyed unprecedented ability to detach from local relationships. That is, the past fifty years was a period in which the interests that represent the flows of goods (e.g., railroad and shipping companies) dominated the interests that represent the fixity of both the surrounding built environment and its associated institutional structures and relationships. However, there are indications that aspects of this relationship may now be changing. Instances of a reassertion of a ‘fixed’ relationship between port and city are visible in efforts to address traffic congestion in and around major freight ports through infrastructure investment, in local resistance to the environmental impacts of goods movement and resultant attempts to (re)regulate port activity, and in the regional rescaling of port governance. As with any ideal-type representation, the specifics of a particular case will depart from its generalized depiction due to the complexities and contingencies involved in any multidimensional and multi-scalar ‘real world’ process. Indeed, the disconnection of ports from their city-regions was never complete; even though they may have abandoned historic waterfronts, most of the world’s major cargo ports remain within, and dependent upon, core metropolitan regions.

How then are we to think about contemporary relationships between maritime ports and the city-regions that contain them? The old, symbiotic relationship between the working waterfront and the trading cities that surrounded them is well documented (see Levinson 2006), as is the commercial, residential, entertainment, and image-making role of the waterfront redevelopments that have replaced them (Brown 2008; Sandercock and Dovey 2002; Gordon 1997). But what role do maritime port interests and users play in the current shaping of city-regions? Despite, or rather because of, the global reach of contemporary supply chains, shipping interests work very hard to secure the conditions that make continued flows of goods, people, and capital possible. We argue that shipping interests cannot secure these conditions solely by disconnecting from the city-regions that contain them and jumping to higher scales of action (see Harvey 1985); in many places, especially in the port city-regions of Western democratic states, they need to (re)establish closer and more fixed relationships in port city-regions. This leads us to ask about the politics of reconnection; who is involved, and at what scales and in which arenas do these politics unfold? And what are the consequences for wider processes of urban-regional development?

We explore these questions through the case of Vancouver. Canada’s busiest port handles about half of the ocean shipping containers that move through all Canadian ports, in addition to cruiseship passengers, motor vehicles, and a variety of resource exports such as coal, lumber, grain, sulphur, and potash. The port is managed by Port Metro Vancouver (PMV), a not-for-profit corporation created by the government of Canada. In a dramatic rescaling of port governance (see Ginnell, Smith, and Oberland 2008), PMV was created in 2008 through the amalgamation of the Fraser River Port Authority, the North Fraser Port Authority, and the Vancouver Port Authority. Amalgamation established a single regional port authority for the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, with responsibility for operating and developing port facilities on over six hundred kilometres of ocean and river frontage.

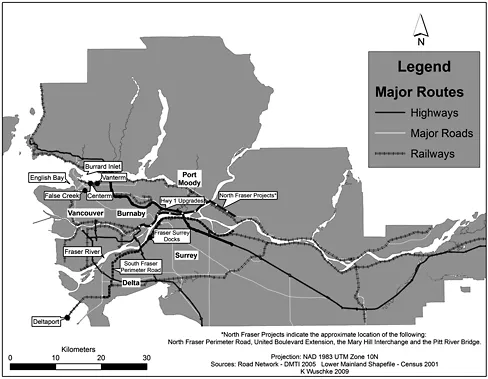

In this chapter we argue that contemporary infrastructure spending decisions in and around the Vancouver port can be understood as the result of an unfolding political contest over the process, terms, and scaling of a reconnection between the port and the city-region. The city-region is the key scale at which this reconnection is taking physical form; this is the scale upon which efficient goods movement depends. We explore how the politics of infrastructure provision have played out across multiple scales, involving networks of actors in federal and provincial governments, public authorities, the transportation industry, and in key import- and export-dependent sectors. Construction of several infrastructure projects, including new bridges and roadways known collectively as the federal government’s Asia-Pacific Gateway and Corridor Initiative and the provincial government’s Gateway Program, is now well underway (see Figure 1.1). These investments, predominantly to the east and south of the core urban area, will undoubtedly reshape the greater Vancouver region. At the same time that they enable goods movement, they will also change commuting and residential development patterns.

We find Cox’s (1998) linked notions of the ‘spaces of dependence’ and ‘spaces of engagement’ useful in understanding the politics of this reconnection. The central question motivating Cox’s seminal paper is to understand whether the politics that play out at a particular scale necessarily directly concern that scale. He argues that they do not. Actors are driven to engage in politics because they seek to secure certain outcomes at a particular scale within their ‘spaces of dependence’. A particular space of dependence is immobile, framed by sunk investments in fixed capital, government jurisdictions, and embedded social relationships. For example, a given port complex or waterfront cannot easily be relocated. To secure these spaces, actors may engage in politics at a variety of scales, within what Cox calls ‘spaces of engagement’. While actors may be deeply concerned to protect the local conditions that are important to them, they will not necessarily engage in politics locally to achieve this outcome. Hence “(l)ocal politics appears as metropolitan, regional, national or even international as different organizations try to secure those networks of associations through which respective projects can be realized” (Cox 1998, 19). Conversely, just because politics plays out at a national (federal) or provincial stage, it may be no less local in its substance.

In the following sections we first discuss general relationships between ports and cities, identifying broad characteristics of the process of disconnection. We then turn to the specific case of Vancouver, highlighting the ways this federally administered resource-exporting port has always been somewhat disconnected from the city. An examination of how and why major port interests have sought to (re)connect to the city-region follows. We close by commenting on the way tensions between fixity and flow of a working waterfront continue to influence the shaping of a city-region.

PORTS, CITIES, AND DISCONNECTION

The results of processes of disconnection between ports and cities are visible in physical infrastructure, port economies, and institutional arrangements. Where coastal configurations have allowed, cargo ports have migrated downstream from traditional river-front locations, leaving behind lands and infrastructure that have, in turn, blighted and then sometimes reinvigorated the post-industrial waterfront (Hoyle, Pinder, and Husain 1988). In Vancouver, physical disconnection can be seen in the construction of a causeway and coal terminal beginning in 1968 and, starting in 1994, a container terminal at Roberts Bank (now called Deltaport; see Figures 1.2 and 1.3), some thirty-five kilometres south of downtown Vancouver and well outside Burrard Inlet, the traditional maritime trade core of the city.

The physical dimensions of disconnection are a direct result of the large economies of scale in containerization. Larger ships imply larger terminals, deeper and wider shipping channels, and higher-capacity landward connections. The scale and shape of modern container terminals has also made them highly impervious to surrounding urban uses, even before the security clampdowns following the events of 9/11. However, where marine cargo terminals moved from the core of the port city to more remote locations, this displaced, rather than eliminated, interactions and conflicts between cargo-related activities and those of residents. For example, trucks carrying containers to and from marine terminals still share local roads and highways with commuters. Hence seaports are also associated with considerable local negative environmental externalities, such as the health impacts caused by particulate matter released from ship smokestacks and diesel-powered trucks (Hricko 2006).

Containerization is both directly and indirectly implicated in economic disconnection. Tight, localized economic relationships between cargo handling operations and urban economies have become loosened. Fewer people are employed in direct cargo handling and many cargo-related jobs need no longer be near the waterfront (Levinson 2006). The economic benefits of ports have not ceased altogether, however; rather, they have become more geographically dispersed. With larger ships calling at fewer ports, the economic hinterlands of ports have become more extensive; ports on the west coast of North America serve producers and consumers across the continent. Ports are now better understood as “elements in value-driven chain systems” (Robinson 2002, 252) than as local economic engines, with relative

negative implications for the economies of port cities. For instance, Grobar (2008) finds that household unemployment and poverty rates are significantly higher in neighbourhoods around the ten largest container ports in the U.S., while Hall (2009) finds that apart from longshore workers on the U.S. west coast, port-logistics workers in major U.S. container ports do not receive higher annual earnings than comparable workers in other places. These labour market outcomes provide further evidence that the economic benefits of ports are disconnected from the city-regions that contain them.

A third dimension of disconnection is institutional, referring to the shift in decision-making power away from local to national and global interests. In many ways, this is a consequence of the economic and infrastructural disconnection between gateway ports and the cities that contain them (Hoyle, Pinder, and Husain 1988). One institutional problem facing many major seaports is the mismatch between the increasingly expansive geographic scale of their port service area and economic hinterland and the often fixed scale of their governance arrangements. Port planners and administrators struggle to secure local support for seaport developments precisely because the economic benefits of seaport gateways have shifted from more local port communities to widely spatially dispersed carriers, shippers, and final customers (McCalla 1999). This has occurred at the same time that the infrastructure requirements of gateway seaports are growing in cost, complexity, and spatial extent. In turn, residents of port cities often find that they cannot influence port decision-making without resorting to lawsuits and protests (Hall 2007; Gulick 2001). Recent port reforms and industry reorganization have arguably exacerbated the problem because they have allowed decision-making power to shift from local public to private sectors. Despite most ports remaining under public ownership, global private-sector actors are able to exercise considerable control over individual terminal facilities (Olivier and Slack 2006). On the west coast of North America, including in Vancouver, long-term leases under a landlord model have become the norm for container terminals.

In the language of fixity and flow, disconnection implies a situation in which capital is able to ensure the condition of continued flow with relative ease; that is, without becoming too fixed in, or dependent upon, any particular place. Nevertheless, transport providers (carriers) and users (shippers) continue to require the seaport terminals that lie at the convergence of marine- and land-based transportation networks. Relative to the communities and polities adjacent to these facilities, shipping corporations are able to exert control over these critical supply chain assets without bearing the full risks and costs of constructing and operating them. For example, Slack (1993) describes how consolidation in the ocean shipping industry accompanied by large public-sector investments in port infrastructure created a situation where shipping lines could play ports off against each other in order to extract leasing, pricing, and employment concessions. Ships continued to call at ports, but did so on terms increasingly favourable to the carriers.

However, there are signs that, in some sense, disconnection is confronting its own limits. A series of research reports by the U.S. federal gov...