![]()

1

Early Life

It was in the sylvan surroundings of Gangamul, the origin of the holy river Tunga in south Karnataka, that Ramabai was born on 23 April 1858.1 Here her father, Anantshastri Dongre, had built an ashram, a residential school for the Sanskrit education of Brahmin boys, in about 1845. A longing to trace her roots led Ramabai to revisit the spot in 1890, when she found the somewhat-dilapidated structure still standing. In a letter to a friend she sketched with lyrical nostalgia the square-mile area of the forest which her father had cleared for his home.

She speaks of the River Tunga in its infancy, its banks adorned with a variety of ferns and with branches of trees gracefully drooping over the current which was cool, crystal-clear and sweet. All manner of animals including wild beasts inhabited the forest in which this small spot still retained signs of former human habitation, marked also by the flowering plants her mother had lovingly planted. Ramabai’s love of nature and her pride in her parents’ achievements, symbolized most tangibly by the ashram, burst through every word: ‘The whole ground seemed hallowed with the association of my beloved parents. The clear blue sky which looks like a round canopy over this place looked more beautiful than any other sky that I had ever seen.’2

*

Uniquely, Ramabai’s life story usually starts four decades before her birth – with the student years of her father, Anant Dongre whose dramatic and eventful life merits a separate narrative.3 In about 1796 he was born at Mal Heranji (or Herambi) near Mangalore in south Karnataka, in a Chitpavan Brahmin family whose ancestors had migrated from Maharashtra a few generations earlier. Married early according to the prevalent custom, but against his wishes, he ran away from home to study Sanskrit texts at the religious establishment or math of Shankaracharya at Shringeri. At 18 he went to Pune to study further with Ramchandra-shastri Sathe, teacher of Peshwa Bajirao II who was the most powerful Maratha ruler at the time, though technically the prime minister of the Maratha sovereign or Chhatrapati based at Satara. During his four years at Pune, Dongre at times accompanied his guru to the Peshwa’s palace and heard the Peshwa’s wife reciting Sanskrit verses in her clear and mellifluous voice. The pleasant experience seemed nonetheless shocking at a time when custom forbade women even simple literacy in Marathi, let alone a knowledge of Sanskrit – the ‘divine language’ reserved solely for Brahmin men. It inspired in him a reformist desire to emulate the ruler, and was to indirectly cause a revolution in women’s education in western India decades later through his daughter. Ramabai’s intellectual roots thus reached into the twilight of the precolonial reign of the Peshwa (also Chitpavan Brahmin by caste), just before Bajirao II lost his political power to the East India Company’s Mumbai-based government in 1818.

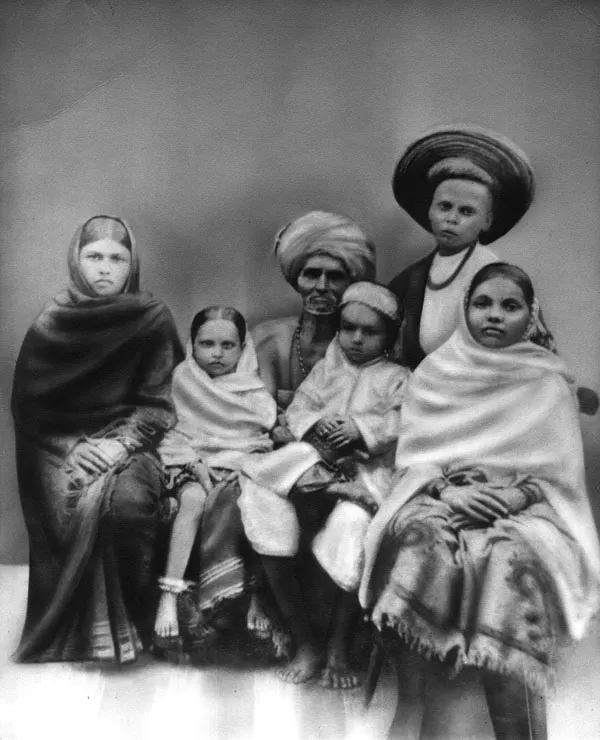

Plate 1 The Dongre family: Lakshmibai, Ramabai, Anantshastri, a son, Srinivas (standing) and Krishnabai, c. 1864

The defeated Peshwa was immediately exiled by the company government to Brahmavarta (or Bithoor, near Kanpur) in North India. Sathe-shastri accompanied his master, but only after bestowing upon Dongre the title of ‘shastri’, in the manner of an educational degree. In the region of Maharashtra, the upheaval caused by the company’s colonization of the Peshwa dominions was still survived by part of the multiple Brahmin hegemony, now based on religious, educational, economic and social supremacy, despite the loss of political-military dominance.4

After Anantshastri’s return home, his attempts to educate his wife were frustrated by the older and conservative family members. Soon he went to the court of Krishnaraj Vodeyar of Mysore in order to earn money. Here he was very successful thanks to the esteem in which the royal guru held Sathe-shastri, testifying to the larger networks of learned men across the country. During his ten years in Mysore, Anantshastri amassed a fortune.

About this time his father wished to make a pilgrimage to Kashi (or Banaras). The dutiful son took along the whole family, with relatives, friends and servants, totalling 60 persons travelling with a palanquin, two carriages and 12 horses. This grand travel arrangement was enabled by the generosity of Vodeyar who also gave him a testimonial in the nature of a travel permit to facilitate their passage through the various provinces en route. On the way Anantshastri’s wife died, leaving behind two children – a married daughter and a grown-up son – who had survived out of the several children she bore. After completing the customary pilgrimage, Anantshastri sent home his family and entourage, and stayed back at Kashi for further studies during which he formally became a devotee of Vishnu by joining a Vaishnava sect. He then travelled up to Nepal and was highly honoured by the king with substantial wealth, a palanquin, two baby elephants and other gifts. Years later the elephant caparisons and some other artefacts were still preserved, and found their way into Ramabai’s childhood memories.

Anantshastri now made his way towards Gujarat, a region venerated by Vaishnavas. On the way he stopped at the holy town of Paithan in Maharashtra in about 1840. The 44-year-old Anantshastri made a deep impression on an impoverished Chitpavan Brahmin pilgrim, Abhyankar, from Wai near Satara in western Maharashtra, who gave him his nine-year-old daughter Amba in marriage. The ceremony was promptly performed, the girl’s first name was changed to Lakshmi, and both parties continued on their way.5 A match so unequal in age was not uncommon in a society which mandated prepubertal marriages for Brahmin girls and allowed remarriage for widowers even late in life, while strictly forbidding it to widows of any age – even child widows. Even so, the age gap and the perfunctory nature of this ‘most extraordinary marriage’ was to elicit a critical comment from Ramabai herself five decades later when she narrated the well-disguised episode in The High-Caste Hindu Woman (henceforth HCHW; Selection 3, chapter 3). Its only redeeming feature, according to Ramabai, was that the little bride had fortunately fallen into good hands, and was tenderly cared for; but she censures the seemingly careless and casual conduct of the bride’s father.

Back home in Karnataka, Anantshastri started teaching his new bride Sanskrit, causing a furore in the family and community. The regional head of his religious sect threatened to ostracize him. Consequently Anantshastri successfully defended his promotion of women’s education in an open assembly of about 400 scholars and priests during a two-month-long disputation. His arguments, buttressed by citations culled from various Sanskrit religious texts and compiled in a scholarly volume, proved that women and Shudras could learn Sanskrit but not study the Vedas. He left this manuscript in safe keeping with a relative but Ramabai was later unable to access it. Thus was lost a valuable Sanskrit text with an emancipatory potential for the social reform discourse.

*

The need to escape such community pressures drew Anantshastri away from home in about 1844 towards tranquil surroundings conducive to his scholarly activities and young Lakshmibai’s education. He decided to build an ashram in the Gangamul forest on the slope where also starts river Bhadra to later join the Tunga and run as the Tungabhadra into the Arabian Sea Mangalore. The site, gifted by Vodeyar at his request, was about nine miles from Mal Heranji up a rather steep slope, but entirely uninhabited and dangerous. The couple spent its first night in the wilderness without any kind of shelter, with a tiger roaring in the vicinity. The terrified little Lakshmibai, wrapped tightly in her cotton quilt, ‘lay upon the ground convulsed with terror, while the husband kept watch until daybreak’, recounts Ramabai.6

Soon rose up Anantshastri’s ashram which attracted Brahmin boys in increasing numbers during his 13-year stay. The students built their own huts, and the cluster of dwellings made up a sizable community. The ashram also provided hospitable accommodation for pilgrims bound for the sacred origin of the Tunga. Here Lakshmibai matured into an efficient housewife managing the burgeoning household and tending the family’s orchards and cattle, and into a capable mother. Her first two sons died in infancy, then were born Krishnabai in about 1848, Shrinivas in about 1850, another son who died in childhood,7 and finally Ramabai in 1858. Importantly Lakshmibai was by now also proficient in Sanskrit and able to teach the resident students when Anantshastri was away.

Back home in Mal Heranji, the dissensions within Anantshastri’s extended family drove him to sell his property, settle debts incurred by various close relatives and start on a pilgrimage with Lakshmibai and their three children: baby Rama was carried by a servant in a cane basket on his head, as she later related in Englandcha Pravas (Selection 2). The pilgrimage took the family to the chief Vaishnava holy sites all over the country. It included an extended stay in 1871–2 at Dwarka in Gujarat. For years Ramabai cherished fond memories of her childhood strolls on the beach there with her family, as recounted in her account of her voyage to England with the poignant nostalgia of the family’s sole survivor. Significantly, when the visit figured again in her description of her family pilgrimage a quarter-century later, the earlier indulgence was replaced by a sharp critique of meaningless Hindu rituals and gullible devotees, such was the religious transition wrought by the intervening years.8 These travels also encompassed holy sites such as Ghatikachala and Venkatgiri in the Madras Presidency in 1872–4. At Ghatikachala Shrinivas lost much of the family money and ruined his health through expensive rituals and austere religious observances; Ramabai describes the episode in Stri Dharma Niti (Selection 1, chapter 2), withholding the young man’s identity.

The family’s financial condition displayed spectacular oscillations, or rather a downward spiral. The wealth which had enabled long-distance mobility at the start of the pilgrimage in 1858 was gradually dissipated through living expenses and generous holy gifts to Brahmins. Surprisingly Anantshastri seems to have combined his religious preoccupations with some business ventures: he bought shares during Mumbai’s financial boom in the early 1860s.9 This was caused by the American Civil War (1861–5) which cut off the supply of American raw cotton and created an unprecedented demand for Indian cotton from England’s textile mills. The conclusion of the war abruptly ended the boom, destroying many fortunes. Anantshastri had visited Mumbai with his family a couple of times: the daguerreotype family photo (Plate 1) was taken there c. 1864. Ramabai’s claim that at one point he possessed Rs. 175,000 which he lost suddenly supports the premise.

Meanwhile the family pilgrimage continued. Even the critical spirit of her later years did not dull Ramabai’s appreciation of the two progressive strands in her generally orthodox father’s thinking. The first was his insistence on educating his daughters; in young Rama’s case the task devolved upon Lakshmibai because he was almost 70 when eight-year-old Rama was ready for her initiation into Sanskrit studies. Ramabai later described the process thus:

On a fine day at the beginning of the ninth year of my age, at an auspicious time when the stars were favourable, my parents worshipped their special gods and Saraswati, the Goddess of Wisdom, and told me to prostrate myself before the deities and worship them. After asking their blessing on me, my mother gave me the first lesson in the Hindu sacred lore. From that day my education began in right earnest.10

The traditional manner of teaching was for the teacher to speak a whole sentence or verse and for the pupils to repeat it twice after him. A lesson would consist of 1,000 or 2,000 lines, and it was an exhausting experience stretching over a few hours. This oral transmission was necessitated by a lack of printed books; the family’s rare manuscript copies – some bought at a high price and some transcribed by Ramabai’s parents – were highly treasured. In this fashion, the pupils had to commit to memory the vocabulary, grammar, even the dictionary and several other comments and references. By the age of 12, Ramabai had already committed to memory 18,000 Sanskrit stanzas to which more were added later.

Anantshastri’s second progressive initiative was his decision not to arrange an early marriage for Ramabai after the miserable failure of his older daughter Krishnabai’s child marriage. Anantshastri had selected for Krishnabai a boy he had hoped to educate at his own home; however, the lad turned out to be a wastrel and ran away. Anantshastri kept Krishnabai with him, but some years later the young man compelled her to join him under the Restitution ...