This is a test

- 209 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cryptosporidiosis of Man and Animals

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book attempts to provide a broad coverage of current information needed by public health workers, physicians, veterinarians, parasitologists, technicians, and various biologists who encounter or work with the parasitic disease Cryptosporidium.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Cryptosporidiosis of Man and Animals by J. P. Dubey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter1

GENERAL BIOLOGY OF CRYPTOSPORIDIUM

R. Payer, C. A. Speer, and J. P. Dubey

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- I. Introduction and History

- II. Taxonomy

- III. Host Specificity

- IV. Epidemiology

- V. Life Cycle

- VI. Clinical Signs, Pathogenesis, and Lesions

- VII. Immunity and Immunoprophylaxis

- VIII. Treatment

- IX. Control or Prevention

- Bibliography

I. Introduction and History

In 1907 Ernest Edward Tyzzer (Figure 1) clearly described a protozoan parasite he frequently found in the gastric glands of laboratory mice.806 He recognized asexual and sexual modes of reproduction followed by spore (oocyst) formation, noting the presence of an attachment organelle at all stages. Furthermore, he described fecal transmission of spores which contaminated food. Noting that the taxonomic position was uncertain, Tyzzer nevertheless offered the name Cryptosporidium muris. In 1910 Tyzzer described the same organism in much greater detail, proposing Cryptosporidium as a new genus and C. muris as a new species.807 He extended the host range from Mus musculus to Japanese waltzing mice and English mice and speculated that sporozoites liberated from oocysts that matured in the gastric glands might be a source of autoinfection. Although Tyzzer credited J. Jackson Clarke with the first published description of a parasite resembling Cryptosporidium, neither the dimensions of the organism nor the figures presented by Clarke support Tyzzer’s comment.161 Tyzzer’s original description of the life cycle remains remarkably accurate based on confirmation by recent investigators using electron microscopy, except that Tyzzer interpreted the location of the developmental stages of the parasite as extracellular.

In 1912 Tyzzer identified and named a new species — Cryptosporidium parvum, once again providing great morphologic detail.808 He distinguished the new species from C. muris by experimentally infecting mice and showing that C. parvum was smaller and developed only in the small intestine. He concluded that C. parvum was not strictly extracellular, but could not be considered intracellular because it appeared to protrude from the host cell surface. He noted that organisms of similar appearance to C. parvum and having the same relation to the host cells were found in the small intestine of the rabbit.

Tyzzer was first to report on avian cryptosporidiosis.809 He found all developmental stages in the chicken cecal epithelium. They were illustrated but were not well described, probably because he thought they were C. parvum, which he had described previously in mice.

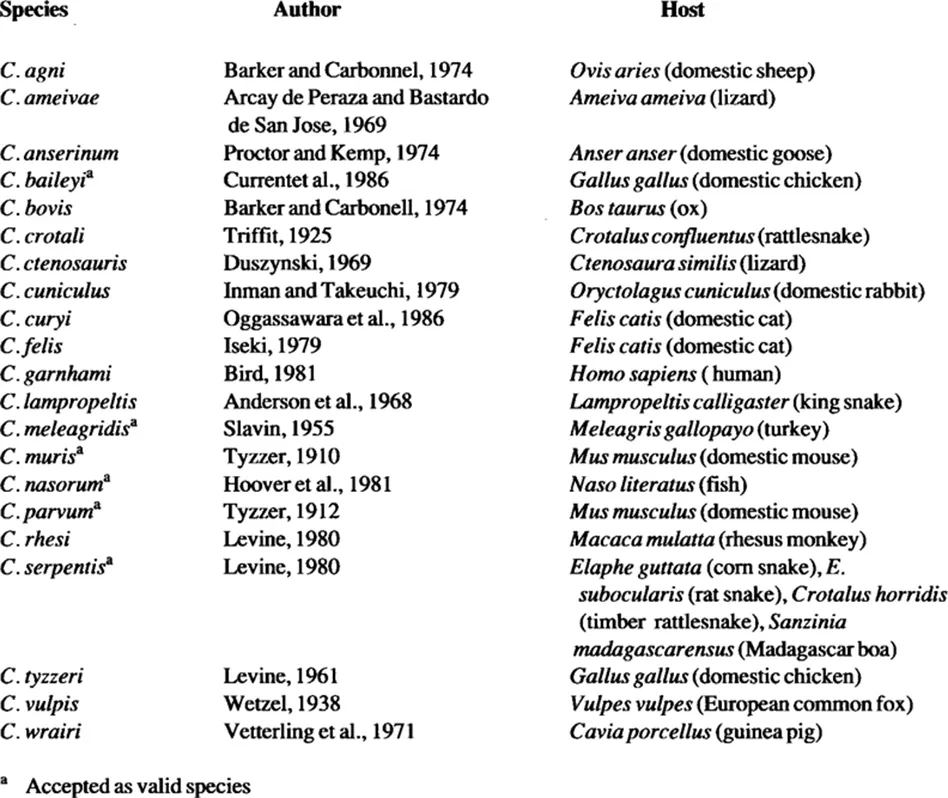

For nearly half a century after Tyzzer’s work, Cryptosporidium was not regarded as economically or medically important and was therefore of interest primarily to taxonomists and serendipidists. A total of 21 species of Cryptosporidium found in fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals were named in large part on the assumption that each host species supported a separate species of Cryptosporidium (Table 1).

In 1955 the first report linking cryptosporidiosis with morbidity and mortality also named a new species — Cryptosporidium meleagridis.740 Diarrhea and a low death rate were found in 10- to 14-d-old turkey poults. However, it was not until 1971 when Cryptosporidium was found to be associated with bovine diarrhea607 that veterinary interest was stimulated.

In 1976 Nime and colleagues591 as well as Meisel and colleagues540 independently reported the first cases of human cryptosporidiosis. After that, relatively few cases were subsequently reported until 1982, when physicians in Boston, Los Angeles, Newark, New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco reported to the Centers for Disease Control that 21 males had severe protracted diarrhea caused by Cryptosporidium in association with Aquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).42 Medical and veterinary interest in the epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention increased substantially thereafter throughout the world.

From 1981 through 1985 the development of several methods to clearly identify the oocyst stage in fecal samples provided health care workers and scientists with the reliable techniques for noninvasive diagnosis. These techniques enabled large-scale epidemiologic surveys, facilitated testing efficacy of chemotherapeutics and disinfectants, and permitted experimental studies on the biology of the organism.

FIGURE 1. Ernest Edward Tyzzer. (Courtesy of National Library of Medicine, Negative No. 85–205.)

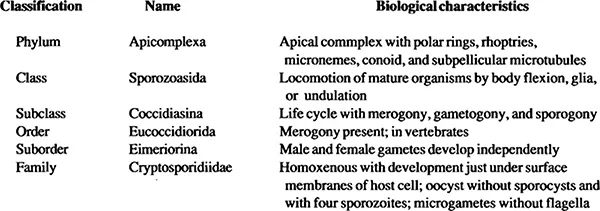

II. Taxonomy

Cryptosporidium is one of several genera of protozoans in the phylum Apicomplexa that are referred to as coccidia (Table 2).236 Generally, coccidia develop in the gastrointestinal tract of vertebrates through all or part of their life cycle. Some require or are capable of extraintestinal asexual development and are referred to as tissue cyst-forming coccidia. These genera include Besnoitia, Caryospora, Frenkelia, Hammondia, Neospora, Sarcocystis, and Toxoplasma. The genera of coccidia that develop only in gastrointestinal or respiratory epthelium without formation of tissue cysts include Eimeria, Isospora, and Cryptosporidium. Species of Cryptosporidium have been named according to the host in which the parasite was found (Table 1). Recent reviews and pertinent cross transmission studies place the validity of many of these species in doubt. For example, C. ameivae is a nomen nudem.458 C. crotali, C. ctenosauris, C. lampropeltis, and C. vulpis were believed to belong to the genus Cryptosporidium based on oocyst morphology, but recent data indicate that the stage reported as the oocyst is actually the sporocyst stage of Sarcocystis.236 Another doubtful species is C. curyi, the oocysts of which from cats are five to six times larger than those of C. parvum. In fish, C. nasorum is the only named species and therefore remains valid pending cross-transmission studies and comparative studies with similar genera such as Epieimeria. C. serpentis457 remains as the only valid species in reptiles.

TABLE 1

Species of Cryptosporidium

Species of Cryptosporidium

TABLE 2

Taxonomic Classification of Cryptosporidium

Taxonomic Classification of Cryptosporidium

From Fayer R. and Ungar, B. L. P., Microbiol. Rev., 50, 458, 1986. With permission.

In birds, C. meleagridis740 and C. baileyi194 and in mammals, C. muris807 and C. parvum808 are accepted as distinct and valid species; C. parvum appears to be infectious for all species of mammals including humans.

Neither subspecies nor strains are recognized or used to designate most coccidia. However, there is a clear recognition of biological differences within some species of coccidia and some studies have noted that C. parvum exhibits such variations. Three isolates in experimentally infected mice showed no morphological or life cycle variation.195 Chromosomal DNA from five isolates could ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Content Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 General Biology of Cryptosporidium

- Chapter 2 Techniques and Laboratory Maintenance of Cryptosporidium

- Chapter 3 Waterborne Cryptosporidiosis

- Chapter 4 Cryptosporidiosis in Humans (Homo Sapiens)

- Chapter 5 Cryptosporidiosis in Ruminants

- Chapter 6 Cryptosporidiosis in Pigs and Horses

- Chapter 7 Cryptosporidiosis in Cats, Dogs, Ferrets, Raccoons, Opossums, Rabbits, and Non-Human Primates

- Chapter 8 Cryptosporidiosis in Rodents

- Chapter 9 Cryptosporidiosis in Birds

- Chapter 10 Cryptosporidium Spp. in Lower Vertebrates

- References

- Index