1 Introduction

Crosslinguistic influence in Singapore English

Some things that a visitor to the tropical island of Singapore definitely will not miss are the clean and green cityscape, the amazing variety of food available, and the unmistakable sounds of Colloquial Singapore English. Colloquial Singapore English is the local lingua franca that developed from a complex contact situation between several distinct languages. The three other official languages of Singapore – Chinese, Malay, and Tamil, have all played a role in shaping Colloquial Singapore English to varying extents, making it uniquely Singaporean. In this study we will investigate the speech of twenty-four Singaporeans and examine the way in which an individual’s use of English is influenced by his or her ethnic language. Such influence from one language on another is known by many terms – interference, language transfer, crosslinguistic influence, and others. For the purposes of this study, the term crosslinguistic influence is used as a cover term for the various kinds of crosslinguistic influences observed in Colloquial Singapore English. The term crosslinguistic influence is chosen because it is one of the more conventional cover terms for the phenomenon in studies of contact languages and second language acquisition.

The phenomenon of crosslinguistic influence is of great interest to researchers in a wide range of fields that include language acquisition, language attrition, language contact, and studies of bilingualism and multilingualism. Crosslinguistic influence is the way in which existing linguistic knowledge of a bilingual, broadly defined as a person who knows two or more languages, affects the way he or she acquires and uses an additional language. In order to truly understand how bilinguals, both in a classroom setting or in a language contact situation, acquire and use his or her languages, we need to understand crosslinguistic influence first. Crosslinguistic influence is usually divided into two main types: positive and negative transfer. Positive transfer is when crosslinguistic influence facilitates the learning of the target language and leads to grammatical output in the use of the target language. On the contrary, negative transfer is crosslinguistic influence which leads to ungrammaticality or errors in the use of the target language. The focus of this book will be predominantly on negative transfer in the Singaporean context because it is comparatively easier to identify and quantify, and is therefore more suitable for statistical analysis compared to positive transfer.

It is hoped that the case studies of crosslinguistic influence in a language contact situation like Singapore will help shed light on some of the complex processes behind crosslinguistic influence. To this end, the interaction of crosslinguistic influence with various social and linguistic factors in the three different linguistic domains of morphology, semantics, and discourse is investigated in this study. Furthermore, ideas from second language acquisition will be incorporated into the analysis of the various phenomena to help us better understand crosslinguistic influence in Singapore. Second language acquisition is important to our understanding of crosslinguistic influence because of shared general cognitive processes of bilingual language acquisition and production, both in and outside the classroom. Additionally, unlike some language contact situations where substrate or ethnic languages are no longer spoken, the ethnic languages in Singapore are still very much integral to each Singaporean’s daily life. This means that English or their ethnic language is truly a second language for all Singaporeans, and they are experiencing many of the cognitive processes of acquiring a second language.

This book on crosslinguistic influence in Singapore English represents a novel approach to the study of crosslinguistic influence in language contact situations by unifying both social and linguistic aspects of the phenomenon using statistical methods. Even though statistical methods like multivariate analysis are commonly used in sociolinguistics, they have not been commonly used to answer the specific question of the way in which crosslinguistic influence interacts with social and linguistic factors. In short, statistical tools like logistic regressions and Poisson regressions are powerful tools for studying crosslinguistic influence because they provide us with information regarding the relative strengths of each social and linguistic factor, and their interactions with crosslinguistic influence. This allows for a far more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon.

The rest of the book is structured as follows: The rest of Chapter 1 will give the reader a brief summary of the major theoretical studies of Singapore English and conclude with how a study of the linguistic and social aspects of crosslinguistic influence may complement previous studies of Singapore English. Chapter 2 consists of two main parts. The first part of Chapter 2 briefly introduces the history and use of English in Singapore, and the second part of the chapter examines the rich linguistic diversity of Singapore, and introduces to the reader how Singaporeans juggle the use of multiple languages in their daily life. The juggling of languages includes selecting an appropriate language for different interlocutors, and the phenomenon of codeswitching. Two hypothetical case studies will be provided to illustrate how typical Singaporeans utilize their linguistic resources in their everyday lives. The third chapter not only provides the reader a general framework for the study of crosslinguistic influence that considers both social and linguistic aspects of the phenomenon, it also provides the reader with a practical toolkit for the comprehensive study of the social and linguistic aspects of crosslinguistic influence in language contact situations. In addition to the toolkit for the study of crosslinguistic influence, this chapter also describes the psychological basis why parallel constructions between Colloquial Singapore English and the ethnic language are a key channel through which crosslinguistic influence operates. Chapters 4 to 6 look at three linguistic domains that are not only core components of language, they also exhibit varying degrees of influence from the ethnic languages. The fourth chapter examines the presence or absence of past tense and plural marking. In this chapter, the variability of past tense and plural marking in Colloquial Singapore English is captured by means of logistic regressions that incorporate both social and linguistic predictors. Examples of linguistic predictors include grammatical aspect, lexical aspect, and priming; while examples of social predictors include age, ethnicity, education, attitude toward English, and dominance of English. The chapter also includes in-depth analyses of interview transcripts to flesh out how linguistic and social factors influence an individual’s language in specific linguistic contexts. The fifth chapter looks at three Colloquial Singapore English words – already, got, and one, that function similarly to their equivalents in the ethnic languages. Not only will an account of the way in which these functions came to be transferred to Colloquial Singapore English be provided, the way in which the presence of parallel constructions between ethnic languages and Colloquial Singapore English influence the synchronic use of these words will also be revealed. Lastly, the fifth chapter will also investigate how crosslinguistic influence motivated by parallel constructions may be strengthened or weakened by individual-level social factors like one’s language proficiency and attitude towards various languages. The sixth chapter focuses on three Colloquial Singapore English discourse particles lah, leh, and lor. Previous studies like Leimgruber (2009) and Smakman and Wagenarr (2013) have shown that the three ethnic groups of Chinese, Malay, and Tamil, differ quantitatively in their use of clause-final discourse particles. As this chapter demonstrates, the three ethnic groups differ quantitatively because of the presence or absence of parallel constructions between each group’s ethnic language and Colloquial Singapore English. Additionally, the process by which individuals create their own unique speaker style through the creative use of discourse particles that achieve novel pragmatic purposes will also be described in this chapter. The seventh and final chapter provides a summary of the major findings in Chapters 4 to 6, and an overall picture of the way in which the concept of salience can determine whether social or linguistic factors might be more prominent for a particular linguistic feature. Additionally, the chapter also briefly discusses the implications of the concept of parallel constructions for the fields of language pedagogy, second language acquisition, and contact linguistics.

Previous studies of Singapore English

In this section a brief summary of the major theoretical studies of Singapore English will be introduced to the reader before we conclude with how a study of the linguistic and social aspects of crosslinguistic influence may complement previous studies of Singapore English.

Theoretical studies of Singapore English can be broadly categorized according to their research focus into two categories – those taking a structural approach and those taking a non-structural approach. On the one hand, studies of the structural approach are mainly interested in providing a linguistic explanation of the unique structures and functions that exist in Singapore English. For instance, why Singaporeans use already as an aspect marker. On the other hand, studies taking the non-structural approach are mainly interested in using social factors to explain the variability observed in Singapore English. For instance, why Singaporeans speak differently when talking to different individuals.

Two representative studies of the structural approach include Bao’s (2015) system-based model of transfer and Ziegeler’s (2015) theory of Merging Constructions. Bao’s (2015) system-based model of transfer states that if there are suitable morphosyntactic elements in the lexifier language, a grammatical system from the substrate language may be transferred to the contact language. On the other hand, if there are no suitable morphosyntactic elements in the lexifier language, the whole grammatical system or parts of the grammatical system will not be transferred. In this sense, the lexifier language acts as a filter of substrate transfer. An example from one of the substrate languages, Southern Min, can illustrate this. The Southern Min verb ho ‘give’ functions not only as a ditransitive verb, but also as a marker of passive voice. The morphosyntactic frames for these two functions are [ho NP NP] for the ditransitive verb, and [ho NP V] for the passive marker. According to Bao (2015), since the lexifier language, English, acts as a filter, the frame [give NP NP] is commonly used in the contact language, Singapore English because the same frame exists in English too. On the contrary, the frame [give NP V] is rarely used in Singapore English because it does not exist in English. In short, Bao (2015) provides us with an explanation of why certain substrate functions are transferred into Singapore English while others are not.

Ziegeler’s (2015) theory of Merging Constructions uses a construction-based approach to explain the appearance of novel functions in Singapore English that are not derived from either the substrate languages or the lexifier language. An example of a novel function is the experiential aspect of Colloquial Singapore English ever. In Standard Singapore English ever functions as a minimizing quantifier that usually appears in questions like (1). In addition to being a minimizing quantifier, Colloquial Singapore English ever also marks experiential aspect and appears in contexts like (2). For both cases there is an inferential meaning that the action can be repeated. It is this semantic link between Colloquial Singapore English ever and Standard Singapore English ever that allows Colloquial Singapore English speakers to view it as a single construction.

- (1) Have you ever been to Malaysia?

- (2) I ever go Malaysia.

- ‘I have been to Malaysia.’

The non-structural approach to the study of Singapore English includes various sociolinguistic models proposed since the 1970s. Since then, various sociolinguistic models have been proposed to account for the linguistic variation found in Singapore English. They are Platt’s (1975) Post-creole Continuum model, Pakir’s (1991) Triangle model, Poedjosoedarmo’s (1995) modified Triangles model, Gupta’s (1994) Diglossia model, Platt’s (1977) Polyglossia model, Alsagoff’s (2007, 2010) Cultural Orientation model, and Leimgruber’s (2013) Indexicality model. What these models have in common is the use of social factors in explaining the alternation between Standard Singapore English and Colloquial Singapore English. For example, the same individual using Standard Singapore English to speak to her teachers and Colloquial Singapore English to speak to her friends. Another example is an individual alternating between Standard Singapore English and Colloquial Singapore English features within a single sentence to convey different attitudes and stances. What follows is a brief summary of each sociolinguistic model; for a fuller discussion of the pros and cons of each individual model please refer to Leimgruber (2013) or Ziegeler (2015).

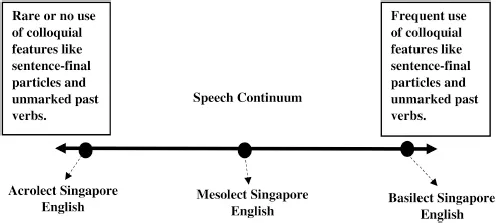

Platt (1975) applies De Camp’s (1971) concept of a post-creole continuum to Singapore English. In this model lects in Singapore English form a continuum ranging from basilect to acrolect (see Figure 1.1). Basilect is the speech variety that is most dissimilar from English and acrolect is the speech variety that most resembles English.

‘An individual’s position on the continuum, coupled with socioeconomic and educational factors, [determines] the number and types of sub-varieties which are at his disposal (Platt 1975: 369).’ Two important points to note are 1) an individual with a higher socioeconomic status and/or had received more education will command a wider possible range of lects; 2) all speakers have access to the basilect.

Referring to Platt’s (1975) model as a ‘cline of proficiency’, Pakir’s (1991) triangle model builds on Platt’s (1975) model by introducing an additional dimension of variation – a cline of formality. For her, variation in Singapore English can be captured by the English proficiency of the individual and the formality of the speech context. For instance, an individual with a higher English proficiency will have command of a wider range of sub-varieties or speaking styles and would be able to shift from Colloquial Singapore English to Standard Singapore English when the formality of a situation requires so. This is similar to Platt’s (1975) approach, the range of styles an individual command is assumed to be directly related to the education level of a person, which is taken as the indicator of English proficiency.

Figure 1.1Sub-varieties of Singapore English available to speakers in the Singapore speech community

Modifying Pakir’s (1991) triangle model, Poedjosoedarmo’s (1995) model shifted the middle and bottom triangles downwards and placed them outside of the biggest triangle. Such a change means that acrolectal speakers do not have command of the full range of mesolectal varieties. Additionally, both acrolectal and mesolectal speakers are not able to speak the basilect as there is no overlapping region between the bottom triangle and the other two triangles. Figure 1.2 is a Venn-diagram representation of the relationships between acrolectal speakers, mesolectal speakers, and basilectal speakers according to Poedjosoedarmo (1995). This is in contrast to Pakir’s (1991) triangle model, where the acrolectal speaker would have full command of both mesolectal ...