![]()

Section 1

Aphasia Therapies of the Past

SOME THEORIES AND THERAPEUTICS BEFORE THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

There is little general agreement even now in the 1980s on the most effective, the most logical, or even the most enjoyable way of undertaking the re-education of aphasic patients. The methods used depend ultimately on a conception of the nature of the impairment in aphasia and of the character of the therapeutic process. We will briefly trace the history of aphasia therapy through the centuries, both because it can clarify the relationship between theory and therapy and because many of our current methods are not as new as we may have thought. This will lead on to a critical survey of the main contemporary schools the next section.

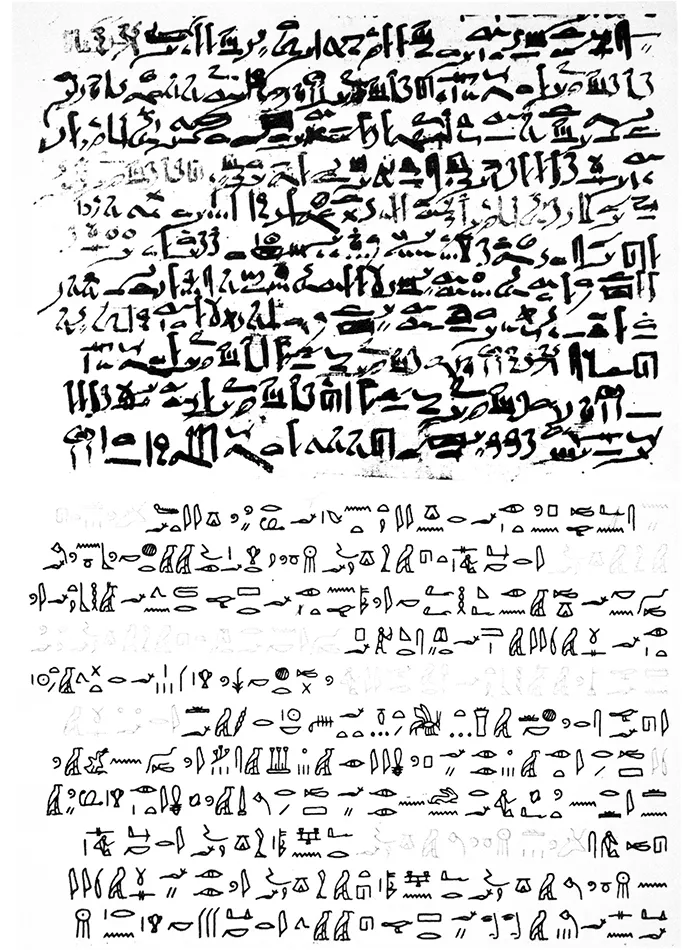

The view that systematic language re-education can achieve little beyond morale boosting for patients with damage to certain areas of the brain is still held by a surprising number of neurologists in several countries (e.g., Hopkins, 1984). This position is not original; an early example of extreme pessimism is that of the ancient Egyptian surgeon-author of the Edwin Smith papyrus of around 2800 BC, who wrote (“Case 20”):

Thou shouldst say concerning him: One having a wound in his temple, penetrating to the bone, (and) perforating his temporal bone; while he discharges blood from both his nostrils, he suffers with stiffness in his neck, (and) he is speechless. An ailment not to be treated. (Breasted translation, 1930, p. 286)

The last sentence would seem to mean that no treatment was offered at all, but the reader is relieved in reading on to find some prescription of palliatives: “Now when thou findest that man speechless, his relief shall be sitting; soften his head with grease, (and) pour milk into both his ears.” (The grease, one is told, came from the fat of animals: gazelle fat and the grease of the serpent, the crocodile, and the hippopotamus.) The description and recommendations for Case 22 (p. 290), where there is ‘a smash in his temple” (with fragments of bone visible in the interior of the ear), are very similar. In an ancient gloss some 500 years later the surgeon explains the archaic Egyptian word for speechless: “As for ‘he is speechless,’ it means that he is silent in sadness, without speaking ... (p. 296).”

The author reveals some understanding of the brain’s function, including the realisation that it controls movements of the body; he also mentions the importance of observing which side of the body has been injured. Breasted suggests that this shows “an astonishingly early discernment of localisation of function in the brain (Breasted, op.cit, p. xv)”; however, it is not clear that the Egyptian surgeon, Imhotep, understood this significance of his observations for modern readers. He was probably only an acute observer of his patient’s condition.

At all times, past and indeed present, treatment of the consequences of brain damage has depended on the medical, surgical, and re-educational measures available, as well as the physician’s conception of the character of the disorder, imhotep, the reputed surgeon-author of the papyrus, clearly lacked the knowledge and facilities for treating a major cause of speechlessness—that is to say, a head wound—and for staving off early death; restoration of higher cortical functions would scarcely have been even an academic matter.

From the point of view of aphasia therapy the Hippocratic Corpus is disappointing to read. It is often unclear from the original text whether the speech disturbances described are of language, articulation, or voice, or a combination of these, and treatment is largely confined to primary symptoms. Head wounds are to be “plugged with a plaster of dough from fine barley meal, kneaded with vinegar and boiled, to make it as glutinous as possible (Hippocrates, On Wounds in the Head, XIV, Withington translation, 1968, p. 33).” This treatment may have had some real beneficial effect; bread dough poultices can encourage the growth of penicillium moulds that could have inhibited bacterial infection. The author here, like the author of the Edwin Smith papyrus, noticed the association of these disturbances with paralysis of the other side of the body. Most of the cases in the Hippocratic Corpus where loss of speech is mentioned are poorly described and it is impossible to be sure whether a true language disorder was present; the case most likely to be an aphasia in modern terms is Case XIII in Epidemics 1, A pregnant woman developed a fever, and on the third day:

Pain in the neck and in the head and in the region of the right collar-bone. Quickly she lost her power of speech, the right arm was paralysed, with a convulsion after the manner of a stroke; completely delirious . . . Fourth day. Her speech was recovered but was indistinct; convulsions; . . . (Hippocrates, Epidemics 1; Jones translation, 1923, p. 13)

By and large, lack of precision in specifying which aspect of speech was disturbed limits the scientific interest of the cases in the Hippocratic Corpus and many subsequent accounts up to the early nineteenth century. There is indeed still lack of agreement on the nature of certain types of aphasia: for instance, whether they are primarily motor or primarily linguistic (a point of utmost important for therapy), and it could be that our successors with a finer diagnosis will criticise us in turn for ambiguity in reporting.

FIG. 1. The first written description of aphasia: Case 19 in the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, reputed to have been written by the surgeon Imhotep in about 2800 BC. The top half of the figure shows a copy, made in about 1800 BC, of the original papyrus; this is in hieratic script—a fast, cursive form of hieroglyphics. The bottom half is the hieratic text transcribed into the corresponding hieroglyphics. The fainter parts of the text were written in red in the original papyrus.

Some further discussion of prevalent conceptions of aphasia in the long period 30 to 1800 AD is a necessary background for the accounts of different types of therapy that will follow. Over succeeding centuries two primary notions of the nature of aphasia recur: first, as a disorder of memory for words; and, second, as paralysis of the tongue. This dispute still continues, in a somewhat different form. Many observers have stressed the mnestic aspect of acquired speechlessness. Pliny the Elder allocates his best-known descriptions of anomia, alexia, and agraphia to the section in his writings on memory in general, although he does maintain that disease or injury may affect a “single field of memory” in some cases (e.g., Natural History, Book VII, XXIV, 88). Johann Schenck von Grafenberg of Strasbourg (1530-1598), author of Observationes medicae de capite humano (1585) and other medical works, was, according to Trousseau, one of the early physicians who appreciated the essential nature of aphasia: in other words, he agreed with Trousseau. Schenck von Grafenberg observed that the patient’s tongue was frequently not paralysed and he attributed speech disturbance to abolition of the faculty of memory:

I observed frequent cases after an apoplectic attack . . . there being certainly no paralysis of the tongue, but an inability to speak; the faculty of memory was abolished and no proffered words came to help. (Schenckius, 1644, p. 180; our translation)

Many other physicians had long realised that speech could be lost without paralysis of the tongue. Nevertheless, throughout the Middle Ages and at times afterwards, speech loss following cerebral lesions was often ascribed to this cause, even when, as is clear from the context, the tongue was perfectly mobile and it was the linguistic code that was defective. The treatment was commonly cauteries and blisters applied to the neck in the hope of thereby stimulating the tongue. (And see Castiglioni, 1947; Critchley, 1970; Soury, 1899).

Soury (1899) draws our attention to some relatively encouraging reports by two sixteenth century doctors, both of which mention a successful treatment, although surgical rather than logopaedic. Nicola Massa, a Paduan physician and specialist in syphilology, described the case of Marcus Goro, a young man who lost his speech after a severe halberd injury, resulting in a fracture of the skull and damage to the meninges and the brain substance as far as the base of the skull. When Massa was called in some eight days later, after other doctors had attempted some surgical treatment, he found the young man still speechless. Although the other surgeons had seen no bone fragment in the brain substance, Massa was convinced that part of the bone must still be lodged in the brain. He was able to extract the fragment of bone from the open wound with a delightfully happy outcome. The patient immediately began to speak, saying “Ad Dei laudem, sum sanusH (“God be praised, I am cured!”), or possibly the equivalent in the vernacular (Massa, 1558, pp. 90 and 91). This drew great applause and admiration from the doctors, senators, and others in attendance.

The second of these physicians, Francisco Arceo, described the head injury of a workman who was struck on the head by a stone, resulting in a depressed fracture, which left the patient motionless and speechless for several days (Arcaeus, 1658). Arceo then replaced most of the bone fragments, noting that the meninges were inflamed. Three days later the patient began to speak and in due course recovered completely.

Ambroise Paré (ca. 1509-1590), perhaps the greatest surgeon of the Renaissance, made important contributions to the treatment of wounds, including wounds of the head, sustained on the battlefield (Paré, 1628, pp. 321, 337 ff). The invention of firearms had produced new types of battle wounds and posed the gravest problems to surgeons at the end of the Middle Ages and in the Renaissance period. Paré discovered during a campaign that the conventional treatment of cauterising wounds by pouring on boiling oil and water was dangerous and ineffective in addition to being exceedingly painful and distressing. Desiring to do something positive as well as refraining from the barbarous application of boiling oil, Paré, ever a humane surgeon, substituted a digestive made of the yolk of an egg, oil of roses, and turpentine. At least two of his cases of battlefield head injuries, in those precarious times, had a relatively good outcome. One was a servant (lacquay) of Goulaines, who suffered a rapier wound to the left parietal lobe, and although seeming well immediately afterwards developed a fever later “and lost his speech ... (p. 372).” The patient was bled and clysterised (given an enema) and the wound was opened to remove some diseased bone, whereupon he made a good recovery. Another case concerned a page of the Marshall of Montjean, who suffered “deafness” as a result of a temporo-parietal lesion from a blow from a stone. Paré again administered a successful surgical treatment and the page was restored to health, although the “deafness” persisted (p. 375). It is not clear whether this was a true deafness or a genuinely aphasic difficulty in language comprehension. Paré mentions that patients with head wounds progressed better in Avignon than in Paris. Eldridge (1968), in her history of speech therapy, gives a lively account of the ministrations of this barber-surgeon to war casualties, but confines it to his treatment of injuries to the peripheral speech organs and certain ingenious prostheses and offers us little on aphasia therapy for head injuries. It is probable that the great majority of such patients died within a short time—presumably, “an ailment not to be treated . . .,” in the phrase of the author of the Edwin Smith papyrus.

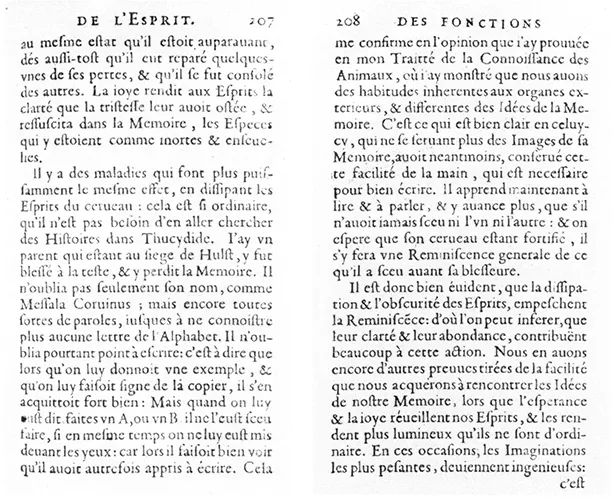

More interesting in terms of aphasia therapy, with welcome precision of details, are accounts of Pierre Chanet (1649), Johannes Schmidt (1624-1690) and Peter Rommel (1643-1703). A reference of Critchley’s (1970) leads the interested reader to the original account by the Sieur Chanet (1649). Here Chanet describes how a relation of his, wounded at the siege of Hulst in the Low Countries, “forgot” all kinds of words and the letters of the alphabet, although he could still copy letters. It is of particular significance for speech therapists that he was reported as:

Now learning to read and speak . . . and making progress ... for he could do neither the one nor the other, and it is hoped that, his brain being now strengthened, he will have a general recollection of what he knew before he was wounded. (Chanet, 1649, p. 208; our translation)

FIG. 2. Head wounds: the causes of traumatic aphasia in mediaeval Europe. From Jacopo Berengario da Carpi’s 1535 book on fractures of the skull.

FIG. 3. The first description of re-education in aphasia; Pierre Chanet’s account of his relative’s aphasia after a head wound at the Siege of Hulst.

Johannes Schmidt’s description (1676) of the patient Nicolaus Cambier, left with motor aphasia and dyslexia following an apoplectic attack, which is also of unusual interest in the history of aphasia, was cited by Bernard (1885). Therapy on a broad front was instituted, entailing abundant venesection (blood-letting); stinging enemas “to stimulate the faculties of sleep”; application of various oils and essences to the head, neck, and nose; and, finally, by dint of all these and “by the goodness of God,” the patient improved vastly, albeit still troubled by dyslexia without dysgraphia. This is one of the earliest references to a patient who had severely impaired reading with writing unaffected. In this case some re-education of the disturbed language function was evidently attempted, but “no teaching or guidance was successful in inculcating an understanding of letters in him” (“nullis enim praeceptis, nulla manuductione literarum cognitio inculcan iterum poterat”). With another cerebrovascular patient, Wilhelm Richter, remediation was more successful and Schmidt was able to reteach the alphabet in a short time. The patient then “combined them [the letters] and reached a level of perfection in his reading” (“. . . combinavit sicque ad perfectam lectionem pervenit”). (Cited by Bernard, 1885, pp. 75, 76)

Peter Rommel (cited by Gans, 1914) described a patient with evident aphasia that he called “aphonia” (De aphonia rara, 1683). Here again the terminology is confusing: “aphonia,” or “alalia” was often used to describe speechlessness from any cause from the time of Hippocrates down to the nineteenth century; the distinction between disorders of the voice and the articulators, and disorders of language was not reflected in any consistent use of terminology. Rommel describes how the lady (“uxor Dn. H. Senatoris. . . Matrona honestissima, 52. annorum”) had a right-sided paralysis and had lost all propositional speech after a mild apoplectic attack, but had retained some automatic and serial utterances. She could, for instance, still recite a few prayers and certain passages from the Bible, but only in the order habitual to her. Dr Rommel apparently tried to help her by giving her a few phrases of this kind to repeat (removed from the context), but this proved too much for the poor lady, who after a number of attempts reacted catastrophically and burst into tears. Rommel stresses that her memory and comprehension were excellent. She was able to read but without perfect comprehension. Rommel adds certain details about the patient’s satisfactory state of health and finishes his graphic and well-observed case history on the cheering note that, as far as possible, she managed to lead a contented life (“forte contenta vivit”). (Observation XVI, Petri Rommelii, 1734, cited by Gans, 1914)

The Swedish observer Dalin (1708-1763) reported a case with a more favourable outcome. A 33-year old Swede had a sudden attack of disease resulting in a right-sided paralysis and complete loss of speech. Two years later he was still only able to produce the one word yes, but could sing certain hymns that he had learnt before his affliction, seemingly with good articulation of the words, with a little help given in starting. He could also, again with some help, recite familiar hymns but he had to declaim these “with a certain rhythm and a high-pitched shouting tone.” (Case cited by Benton & Joynt, 1960) A transition in treatment from speech sung along with the therapist, through speech with exaggerated intonation and rhythm, towards more normal speech is the foundation of the modern approach of Melodic Intonation Therapy—MIT (Sparks, Helm, & Albert, 1974).

Here and there in the past medical literature we can find really well-described cases of loss of spoken and written language, but on the whole the period up to about 1770 is unrewarding as a serious scientific introduction to the treatment of aphasia, partly because, as has been mentioned, the symptom-complexes of aphasia remained poorly defined.

Benton and Joynt (1960) provide a summary of the work of Johann Gesner (1769), as well as referring to a number of other early observers of aphasia (see also Benton 1964, 1965). In the history of aphasia, Gesner represents a significant advance. While attributing language deficits following illness such as stroke to a specific impairment of verbal memory, he took pains to point out that they were not part of a general loss of memory, nor due to paralysis of the tongue, but that the defect reflected a breakdown in the ability to associate images or abstract ideas with their verbal symbols. This view distinguishes aphasia from both a disorder of thought or concept, and a disorder of speech production, and locates the problem in the association between concepts and their symbols; it anticipates the basic position of the associationist neurologists of the nineteenth century (e.g., Broca, Wernicke, etc.). Gesner supplies many important details of his cases, noting how, for instance, written language might be impaired; how reading might be differentially affected in the various languages mastered by a patient; and whether patients were aware of their defects. Finally, there is a note on the treatment of a patient whose tongue became paralysed. After:

Spanish flies and venesection he began to speak again but used the same words to name various objects, words that seemed to come from a foreign language. (Benton & Joynt, 1960, pp. 213-214)

There are a number of other vivid accounts of aphasia before the nineteenth century (for example, Oberkonsistorialrat Spalding’s self-observations in 1772, cited by Eliasberg, 1950), but little evidence of any systematic and motivated attempts at language re-education. The story of Dr Johnson’s transitory episode of aphasia is well-known, as is his attempt at assessing his own mental state (“the integrity of my faculties”) (Boswell, 1791, p. 257 in 1901 reprint; see Critchley, 1970). Two days after suffering a sudden loss of speech, he wrote to his friend, Mrs Thrale, describing first how he had felt reasonably well ...