This chapter analyses armed rebellions and government responses to them from colonial to post-colonial times. In the colonial area, the Filipinos had to battle first the Spanish and then the US occupation forces. The first part of this chapter focuses mainly on the Filipino insurgency and US COIN (counter-insurgency). Then, for a brief period came the Japanese. After independence, the Philippines had to deal with one communist agrarian and an Islamic armed uprising. The Islamic armed uprising is still smouldering, and of late, it seemed to have developed transnational connections. Now, let us discuss the Philippines in the colonial era.

Colonialism and insurgency in the Philippines

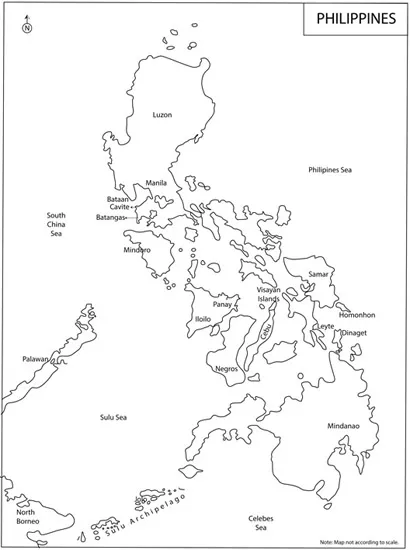

By the end of last decade of the nineteenth century, of seven million people who comprised the population of the Philippines, about half lived in Luzon. Luzon was a Spanish colony since the late sixteenth century. Luzon is the greatest island in the archipelago with an area of 40,420 square miles. Five major linguistic groups inhabit Luzon, and the dominant one is the Tagalogs. This community provided majority of the insurgents against both Spanish and American colonialism. The Spanish ruled the countryside through the Roman Catholic clergy commonly known as friars and the traditional elite (principalia/principales). The latter filled the provincial and municipal offices and functioned as intermediaries between the distant Spanish government based in Manila and the peasant populace of the Philippines. The principales were confirmed in their local power base in return for accepting Spanish royal authority. The Spanish introduced sugar, hemp and tobacco cultivation in the Philippines.3

In 1892, Spain faced an insurgency in the Philippines. The centre of resistance was Andres Bonifacio’s Manila-based Katipunan Society. An amalgam of revolutionary rhetoric, nationalist ideals, Tagalog ethnocentrism and secret society rituals motivated the personnel of Katipunan Society. They demanded independence from Spain through armed rebellion. This society grew in strength in the Tagalog region near Manila.4

From 1895 onwards, Spain also faced an insurgency in Cuba. There were 150,000 Spanish soldiers in Cuba and 40,000 around Manila. However, the Spanish troops were demoralized due to disease and failure to crush the insurgents in both Cuba and the Philippines. In Cuba, rainy season lasts from May to September. Because the streams were transformed into rivers and the roads became impassable, military operations against the guerrillas were almost impossible. When flying columns comprising cavalry moved into the western plains, the insurgents moved into the mountains of central and eastern Cuba. In the narrow mountainous passes, the military columns were frequently ambushed. The Spanish force was divided into bands comprising 20 to 100 men in an attempt to hunt down the guerrillas. The guerrillas conducted hit-and-run attacks on railway lines, telegraph lines and sugar plantations. Most of the Spanish troops were tied up in protecting forts, towns and their vulnerable line of communications. On 25 April 1898, the United States declared war against Spain in Cuba.5

In 1895, Emilio Aguinaldo, a young Tagalog principal from Kawit, Cavite, joined the Katipunan Society. He raised a guerrilla band loyal to himself and controlled the eastern Cavite. In March 1897, he deposed Bonifacio. In 1897, Aguinaldo ordered the formation of village militia/Sandahatan led by officers appointed by the municipal councils. Manned by peasants and led by their village officials, employers, landlords and patrons, the Sandahatan was geared to fight in their home terrain and gradually wear down the occupying power. In December 1897, Aguinaldo was exiled to Hong Kong by the Spanish authority in the Philippines.6

On 1 May 1898, Commodore George Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. The naval battle of Manila Bay made the US Navy supreme in the Philippine archipelago, but Spanish troops held Manila. Dewey requested American ground forces for occupying Manila. On 2 May William McKinley, president of the United States, directed that a military expedition be sent to the Philippines. The logic was that the capture of Manila would force Spain to accept peace in Cuba on American terms. Probably, at this stage, President McKinley was thinking about the permanent occupation of the Philippine archipelago. A contingent of 2,500 men under Brigadier General Thomas M. Anderson left San Francisco on 25 May. A month later when Major General Wesley Merritt came, there were about 10,600 American soldiers in the Philippines.7

On 12 May 1898, Dewey brought back Aguinaldo from Hong Kong in an American ship. This revitalized Filipino resistance against the Spanish. On 24 May, Aguinaldo assumed dictatorial power. On 26 May, Dewey received orders from the secretary of navy John D. Long to avoid any alliance with the Filipino guerrillas. On 12 June, Aguinaldo declared independence to the Philippines. On 24 June, Aguinaldo became president of the Revolutionary Government. Partly due to the actions of the Filipino guerrillas, the Spanish garrisons in the provinces were isolated, demoralized and soon capitulated. On 14 August, Merritt issued a proclamation, declaring that the Americans had not come to make war on the Filipinos. He promised preservation of personal and religious rights of the inhabitants of the Philippines. By the end of 1898, the Filipino guerrillas accepted Aguinaldo’s authority in theory, if not in practice. On 10 December 1898, by the Treaty of Paris, the Philippines was transferred to American control.8

By August 1898, Major General Eklwell S. Otis replaced Merritt. His poor diplomacy compared to that of his predecessor resulted in worsening of relations with the Filipino guerrillas. Meanwhile Filipino forces occupied the suburbs of Manila and refused to vacate them despite American objections that there was going to be no joint occupancy. In February 1899, the Philippines was annexed to the United States.9

On 4 February 1899, the American war against the Filipinos started, and it is known as the Philippine War. Initially, the Filipino nationalist forces followed conventional operations, and the US Army was able to defeat them easily. On 31 March, the Republican capital of Malolos was captured. In April and May, the American forces swept in Central Luzon and in June entered the southern Tagalog provinces. Otis commanded 26,000 soldiers, and of them only 13,000 could be spared for active operation in Luzon. Thus, he lacked adequate manpower to occupy the conquered zones. Repeatedly, the American forces moved through paddy fields and hills, occasionally skirmished with Aguinaldo’s forces, and then returned to Manila. The arrival of monsoon in May resulted in 60 per cent sickness in some of the units. The monsoon season extended from June to September when malaria, dengue fever and dysentery became rampant.10 Overall, the Americans were able to defeat the Filipinos repeatedly in conventional campaigns.

On 30 July 1898, Aguinaldo authorized each Tagalog province to create a battalion of provincial forces, which were to join the three new Aguinaldo regiments of federal troops. They comprised the Republican Army. Simultaneously, he encouraged the formation of revolutionary Sandahatan, town companies that were based on personal and local loyalties. The Republican Army was poorly armed and badly disciplined. The men were taken out of their villages and assembled in big battalions commanded by ‘outsiders’ who could not speak their dialect. Hence, these formations lacked primary group solidarity. Moreover, the principales who formed companies out of their tenants and clients refused to obey orders of outsiders appointed by Aguinaldo.11 Only two-thirds of the Filipino soldiers carried rifles. In addition, Aguinaldo’s regulars were short of ammunition. Hence, they were unable to practice in order to improve their aim. Most of the Filipino soldiers in battle shot high because they were not trained to use the sights on their rifles. Further, the Americans had an edge as regards artillery.12 In addition, Aguinaldo faced serious political challenges from some of his commanders. Lieutenant General Antonio Luna took command of the Filipino forces after the fall of Malolos. Luna’s political ambition resulted in his assassination by Aguinaldo’s bodyguards on 5 June 1899.13

From November 1899, only after Aguinaldo’s forces were shattered in conventional campaigns did the Filipinos make a shift to guerrilla warfare. The guerrillas/militias lived as ordinary civilians and armed with bolo knives or spears. They prepared booby traps, gathered information about troop strength and movement of the Americans and spread the rumour that the Americans were raping Filipino women. General Arthur MacArthur replaced Otis as supreme commander in the Philippines during May 1900. In September, the guerrillas launched several large-scale attacks with the objective of influencing American presidential election in favour of William Jennings Bryan, who had promised to grant independence to the Philippines. Arthur MacArthur realized that merely benevolent civic action would not end the insurgency. Civic action needed to be coordinated with a measured amount of coercion. Arthur MacArthur ordered that all Filipino families who refused to support the Americans by word or deed would be treated as enemies. Prisoners of war were no longer released, and the guerrillas who moved around in the guise of civilians were executed. Many Filipinos who were otherwise neutral but failed to provide information about the insurgents to the Americans were either imprisoned or heavily fined. This reduced the level of cooperation between the local Filipino officials and the insurgents. Further, American and Filipino security personnel conducted patrols during both day and night in the mountains and swamps, which in turn kept the guerrillas on the run. Harassment of the insurgents as well as destruction of property of their supporters reduced the ardour for insurgency among the Filipinos. The Americans captured Aguinaldo in March 1901, and by April, many other prominent guerrilla leaders surrendered.14

Nevertheless, the insurgency continued to smoulder in several regions of the Philippines. By mid-1901, the insurgents were still active in the islands of Samar, Cebu, Bohol and south-west Luzon. Samar’s 5,000-square-mile interior was filled with swamps, mountains and disease-ridden jungles with wild animals. On 4 July 1901, Arthur MacArthur was replaced by Major General Adna R. Chaffee. Chaffee rai...