eBook - ePub

Assessing quality in applied and practice-based research in education.

Continuing the debate

This is a test

- 142 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Assessing quality in applied and practice-based research in education.

Continuing the debate

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

One of the most persistent features of the research environment in the UK over the last decades has been the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE); now more and more countries are following suit by developing their own systems for research quality assessment. However, in the field of education, one of the difficulties with this policy has been that a

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Assessing quality in applied and practice-based research in education. by John Furlong,Alis Oancea in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Expressions of excellence and the assessment of applied and practice-based research

Introduction

In 2004 we were commissioned by the ESRC to undertake a short project exploring issues of quality in applied and practice-based research in education. The ESRC had expressed an interest in such a project presumably because of ongoing public concerns about quality in educational research, much of which claimed to be applied in nature. Though our focus was explicitly on educational research, there was recognition by the ESRC that many of the issues we were likely to consider would have a broader relevance to other social science disciplines such as social policy and business administration that also had a strong applied dimension.

The paper we produced as a result of our short project (Furlong & Oancea, 2006) attracted widespread interest—both in the UK and internationally. In the UK it was widely distributed and discussed and was referred to explicitly in the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) criteria for education; in Australia the paper was published by the Australian Association for Research in Education as one in a series focusing on issues of quality in the run up to their own research quality assessment. However, not all of the responses were positive and the paper also attracted some sustained criticism (Kushner, 2005; Hammersley, 2006).

Our aim in this particular contribution is not simply to reproduce our earlier arguments, nor is it specifically to respond to our critics. Rather we have used the opportunity of writing the opening contribution to this special volume to restate our original ideas, elaborating, developing and refining them where we think that this will help in making them more explicit in the hope of moving the argument on. The sub-title of our original paper was ‘a framework for discussion’. What we present here therefore is a further reflective iteration of our original paper, contributing to what we hope is an ongoing debate on this important issue.

Quality and the changing policy context

The past 20 years have seen growing emphasis on quality in relation to governance, public services, and consumer goods and services. This discourse of quality has also permeated the field of research, to the extent that it has almost replaced in public consciousness earlier debates about ‘scientificity’. Tighter accountability regimes and the scarce resources, available for public research in the late 1980s, coincided with an increase in the policy interest for research assessment, culminating with the creation in the UK of the Research Assessment Exercise. An unplanned consequence of this was the pressure for more articulated definitions of quality in research intended to attract widespread consensus and to justify funding decisions.

The interpretation of both ‘quality’ and ‘relevance’ in public assessments of research, however, generated in many circles increased concerns about the treatment of certain types of research. Somewhat paradoxically, applied research often found itself among those singled out as under threat: what should have been an era favourable to all applied research, some felt, turned out simply to encourage its more instrumental strands. Relevance therefore remained an underdeveloped criterion, awkwardly close to ‘the eye of the beholder’, and worryingly prone to political interpretation. As many have argued, the RAE despite ostensibly supporting applied research (UK Funding Bodies, 2004, para. 47) may have contributed to the reinforcement, rather than the solution, of these problems (see, e.g., the criticisms of the RAE expressed in the Roberts and the Lambert reports of 2003: UK Funding Bodies, 2003; HM Treasury, 2003).

We would suggest that the problem resided, in part, with a narrowing of the ‘official’ concept of quality, which, for lack of a better definition, tended to hover somewhere in the space between scientificity (often defined by reference to the natural sciences), impact (reduced to, for example, observable and attributable improvement in practice), and even productivity (whereby volume was mistaken for an indicator of quality). In such a context, the assessment of applied and practice-based research perhaps inevitably drifted towards simplistic concepts of linear application and technical solutions. In the case of educational research, this happened on the back of long-lasting controversies about the nature of inquiry and of knowledge in the field, and of some already heated disputes about its relevance, quality and impact in the late 1990s (see Hargreaves, 1996; Tooley & Darby, 1998; Furlong, 1998, 2004; Hillage et al., 1998, analysed in Oancea, 2005; Pring, 2000).

Over the course of the study reported here, we found ourselves unable to situate our emerging proposals within the above framework. Our project was therefore an attempt to reframe the problem, by interpreting ‘application’ as a complex entanglement of research and practice, ‘assessment’ as deliberation and judgement, and ‘quality’ as excellence or virtue, in a classical (Aristotelian) sense of the terms. The remainder of this contribution will clarify what we mean by these terms.1 First, it will clarify the scope of our study and what we mean by applied and practice-based research; second, it will outline a threefold understanding of excellence in applied and practice-based education research; and third, it will seek to unpack the meaning of this concept of excellence for research assessment.

The project

As we have already noted, the work reported here started as a project commissioned by the ESRC in 2004 and completed in 2005. The original remit was to explore ways of looking at the quality of applied and of practice-based research in the field of education that might be able to inform fairer assessment criteria. Our initial proposal to the ESRC had two main intentions: to collate and analyse various views on what applied and practice-based research may look like in the field of education; and to explore and systematize the understandings of quality that were underpinning its assessment in a range of contexts. In pursuit of the former, we proposed a literature review and a series of small ‘case studies’ concentrating on several modes of applied and/or practice-based research (e.g., action research, parts of evaluation research, use-inspired basic research) and several initiatives directed towards promoting them. As for the latter, we envisaged the collection of statements of criteria from a diversity of contexts of assessment (publication, funding, degree awarding, review, and use), the analysis of their content and style, the discussion of the conclusions from each of the case-studies and a wider process of consultation (involving, among others, an advisory group of eight). In the end, in addition to an extensive literature review, we conducted five interviews, three workshops and meetings, ten invited briefings and seven small case-studies (discussed and agreed with key persons involved);2 in addition, over 40 sets of criteria in use at the time of the project were submitted to textual analysis.

As the project evolved, and more and more people engaged with the emerging findings, it became clear that what was needed was not yet another set of criteria to add to the ever growing mass of existing checklists, but, rather, a document that would attempt (a) to recognize the diversity of perspectives on applied and practice-based research quality in education, and of the ways in which they build their legitimacy; (b) preserve the importance of methodological and theoretical soundness in applied, as well as in ‘curiosity-driven’, research; and (c) emphasize the principle that research in education ought to be assessed in the light of what it wants and claims to be, and not through a rigid set of universal ‘standards’. In attempting to do so, we realized that such a document would have to stop short of providing any list of criteria that claimed to be comprehensive, discrete, or universally applicable. This realization resulted in a shift, over the life of the project, from a discussion of ‘criteria’ and quality ‘dimensions’ to one of contexts of assessment, modes of research, and expressions of excellence.

A second important shift in our understanding of the task ahead occurred very early in the process. The mass of checklists and indicators, once collated and analysed, proved less helpful than we had hoped. The reason for this was that most of them were stripped not only of contextual information, but also of any explicit indication of their deeper, often conflictual assumptions about the nature of knowledge, about the forms and strength of their warrants, and the (educational, ethical, political, etc) relationship between modes of research and society. Throughout the life of the project, this gradually emerged as the main concern permeating our work. As a result, the framework we proposed was intended to be read not as an attempt to regulate even further what applied research in education ‘should’ look like (though we acknowledge the fact that a weakness of the framework is the fact that it cannot prevent such use), but as part of a struggle to recapture a cultural and philosophical dimension of research assessment that had been lost in recent official discourses.

Complex entanglements of research and practice

The first difficulty that we encountered in our work was defining its scope or coverage. There are many competing, though overlapping views about the specific modes of research to be included under the categories of applied and practice-based research. Some of the more powerful interpretations in the public policy domain in recent years are those of the OECD (2002a) and of Stokes (1997), also urged in the field of education: OECD (2002b) and Feuer and Smith (2004).

The OECD Frascati Manual defines applied research as: ‘original investigation undertaken in order to acquire new knowledge … directed towards a specific practical aim or objective’ (OECD, 2002a, p. 78). They go on to suggest that applied research is undertaken either to determine possible uses for the findings of basic research or to determine new methods or ways of achieving a specific and predetermined objective.

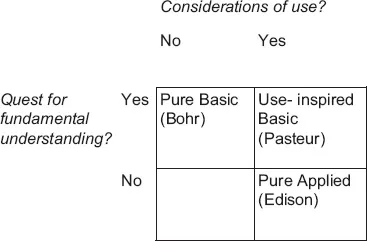

Stokes (1997) on the other hand suggests cross-cutting the idea of ‘use’ with the pursuit of ‘fundamental understanding’ to produce a quadrant model that encompasses ‘pure basic research’, ‘pure applied research’, and then Pasteur’s quadrant—‘use-inspired basic research’ (Figure 1). The latter sort of research, he argues, should address genuine problems, identified by policy-makers and practitioners; such research could thus contribute both to knowledge production and to policy and practice.

Figure 1. Pasteur’s quadrant (Stokes, 1997)

However, many of the assumptions underpinning both of these interpretations remain firmly within an instrumental framework. On the one hand, they see applied research as a means towards attaining predefined aims; these aims are external to the process of research itself, and their attainment coincides with solving practical problems. On the other hand, they seem to embrace a hierarchy of knowledge in which the difference between theoretical, propositional types of knowledge and practical, implicit ones is one of status, rather than of mode. Other proposals are built on similar assumptions. For example ‘strategic research’ is seen by OECD (2002a) and Huberman (1992) as research which aims to combine scientific understanding and practical advancement with researchers becoming engaged in the quite separate political processes necessary to achieve change.

Yet there are models of research that have attracted growing interest over the past few decades that have fundamentally challenged the idea that applied and practice-based research are purely instrumental pursuits. For example, action research (Stenhouse, 1985; Carr & Kemmis, 1986; Carr, 1989; Elliott, 1991), evaluation research, and reflective practice approaches (Schön, 1983), all illustrate how research may contribute to theoretical knowledge while at the same time being part of changing practice in a way that is intrinsically worthwhile. They foster theoretical, as well as practical modes of knowledge, and point up the complexities involved in bringing research and practice together.

What these different models highlight are the variable boundaries within which applied and practice-based research can situate themselves, and their relationships with practice and policy. While this may encourage great interest in them, it allows for even greater disagreement as to how they may be defined and therefore how they might be assessed. In our project, we eventually chose to define applied and practice-based research inclusively, as an area situated between academia-led theoretical inquiry and research-informed practice, and consisting of a multitude of models of research explicitly conducted in, with, and/or for practice.

Expressions of excellence

In considering the issue of quality in applied and practice-based research, the challenges we faced were, however, not merely ones of definition. What our analysis revealed was that quality in applied and practice-based research was peculiarly difficult to pin down because of researchers’ insistence on mixing different forms of knowledge; mixing their theoretical claims and concerns with practical ones. As a result, though in principle it might be possible to judge applied and practice-based research from a purely methodological perspective, this leaves out the most interesting part of the problem—their relationship with practice and policy. Part of the task of seeking a more rounded judgement was therefore to see how notions of quality might respond to the diversity of ways in which applied and practice-based research place their emphasis on the relationship with practice (including policy) and with practitioners and users.

In trying to understand that diversity and possible different conceptions of quality more clearly, we returned to the work of Aristotle.3 Aristotle operated with a distinction between several different domains of knowledge (or of engagement with the world), each with its own forms of excellence that could not be reduced to others. In our account of quality in applied and practice-based research we focus on three such domains, derived from Aristotle’s distinctions: theoresis (contemplation); poiesis (production); praxis (social action). Within each of these domains there is space for excellence, or ‘virtue’, epitomized by three further concepts: episteme theoretike (knowledge that is demonstrable through valid reasoning); techne (technical skill, or a trained ability for rational production); and phronesis (practical wisdom, or the capacity or predisposition t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Introduction Assessing quality in applied and practice-based research in education: continuing the debate

- 1 Expressions of excellence and the assessment of applied and practice-based research

- 2 Mediating academic research: the Assessment Reform Group experience

- 3 Changing models of research to inform educational policy

- 4 Co-production of quality in the Applied Education Research Scheme

- 5 Developing knowledge through intervention: meaning and definition of ‘quality’ in research into change

- 6 Ethics in practitioner research: an issue of quality

- 7 Weight of Evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence

- 8 Assessing the quality of action research

- Index