eBook - ePub

Recognizing Race and Ethnicity, Student Economy Edition

Power, Privilege, and Inequality

This is a test

- 552 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Recognizing Race and Ethnicity, Student Economy Edition

Power, Privilege, and Inequality

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

To better reflect the current state of research in the sociology of race/ethnicity, this book places significant emphasis on white privilege, the social construction of race, and theoretical perspectives for understanding race and ethnicity.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Recognizing Race and Ethnicity, Student Economy Edition by Kathleen Fitzgerald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Thinking About Race

CHAPTER 1

Taking Account of Race and Privilege

Chapter Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Differentiate between race and ethnicity, and distinguish between different forms of racism

- Understand what is meant by the social construction of race

- Describe demographic shifts in American society along racial/ethnic lines

- Explain race at the level of identities, ideologies, and institutions

In August 2006, three nooses were hung from a tree outside a high school in Jena, Louisiana, where a black student had stood the day before. The tree, known by students and faculty as "the white tree," was in an area where white students normally gathered. The incident led to the suspension of three white students and an off-campus fight between a white student and several black students, followed by the arrest and expulsion of the six black students involved in the fight. The small town of Jena became an example of ongoing racial conflict.

The six black students arrested, ranging in age from fifteen to seventeen, faced charges of attempted second degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder for the beating of the white student and were charged as adults, facing between twenty and one hundred years in prison if convicted. The first of the Jena Six to be tried was Mychal Bell, and he was convicted of aggravated battery and conspiracy by an all-white jury and faced up to twenty-two years in prison. His conviction was later overturned because he should have been charged as a juvenile, yet he still spent almost two years in prison. Eventually, all six defendants were charged as juveniles and pled guilty to simple battery.

The story generated national attention, with many arguing that the initial charges of attempted murder were excessive and racially discriminatory. On September 20, 2007, between fifteen thousand and twenty thousand protestors marched in Jena in support of the Jena 6, and similar protests were held throughout the country, leading some to describe this as the largest civil rights protest in decades.

W.E.B. Du Bois begins his seminal work, The Souls of Black Folk (1989:1), with the prophetic statement, "The problem of the Twentieth century is the problem of the color-line." His comment remains true today, but we would instead say the problem of the twenty-first century remains a problem associated with the racial order,* the collection of beliefs, suppositions, rules, and practices that shape the way groups are arranged in a society; generally, it is a hierarchical categorization of people along the lines of certain physical characteristics, such as skin color, hair texture, and facial features (Hochschild, Weaver, and Burch 2012). The United States has not resolved the "race problem," as it has historically been referred to by social scientists, and part of the reason is because white people have never considered it to be their problem to solve. The term race problem implies a problem of racial minorities. Du Bois expresses this implication in his first chapter: "Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question ... How does it feel to be a problem?" (1989:3). Race relations in a society, whether problematic or not, involve all racial groups, including the dominant racial group.

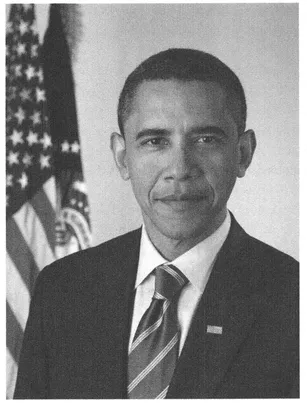

The election of President Barack Obama led to immediate claims in the media that the United States is a postracial society, a society that has moved beyond race, because Obama could not have won the presidency without a significant number of white votes. However, as sociologists point out, Obama may have won the presidential elections in 2008 and 2012, but most whites did not vote for him (Wingfield and Feagin 2010). While Obama won significant majorities of racial minority votes, from 62 percent of the Asian American vote and 66 percent of the Latino vote to 95 percent of the black vote, he won only 43 percent of the white vote in 2008 (Wingfield and Feagin 2010). The kind of opposition he has faced while governing is virulent and unlike anything past presidents have experienced. For instance, he is the only president to have his birthright questioned. Perhaps even more disturbingly, the US Secret Service has reported approximately thirty death threats against Obama daily, which is four times the number made against the previous president (Feagin 2012).

IMAGE 1.1: The election of President Barack Obama, the first African American US president, is evidence of racial progress but not evidence we are a postracial society. Obama could not have won the presidency without a significant number of white votes. However, most whites did not vote for him, while significant majorities of racial minority voters did. (Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppbd-00358)

While much has changed over the last century in terms of race, race remains a central organizing principle of our society, a key arena of inequality, and the subject of ongoing conflict and debate. Race also influences our identities, how we see ourselves. Ongoing evidence of the continuing significance of race manifests in both significant and obscure ways, as the following exemplify:

- The July 2013 acquittal of volunteer neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman for the killing of unarmed teenager Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, has resulted in racially divided opinions on the verdict: 86 percent of African Americans are dissatisfied with the verdict compared to 30 percent of whites, while 60 percent of white Americans think the racial dynamics of the case are being overemphasized compared with only 13 percent of blacks who feel the same way (PEW Research Center 2013).

- A mere ten days before the 2012 presidential election, polls showed that racial attitudes in the United States had not improved since the election of the country's first black president, with 51 percent of Americans expressing explicit antiblack attitudes, up from 48 percent in 2008 (Ross and Agiesta 2012).

- The average white student attends a school where 77 percent of their classmates are also white (Swalwell 2012).

- Several black nurses have sued the Michigan hospital where they work for acquiescing to the demands of a white supremacist who, after exposing his swastika tattoo, demanded that no nurses of color be allowed to care for his baby (Karoub 2013).

- The Pew Research Center released data showing that Asian Americans now outpace Latinos as the fastest-growing immigrant group in the United States (Garafoli 2012).

- Over the past decade, research finds white criminals seeking presidential pardons have been almost four times as likely as racial minorities to receive them (Linzer and LaFleur 2011).

- In 2012, a student at Towson University proposed a campus White Student Union while anonymous students at Mercer University posted fliers on campus declaring November and December to be "White History Month," in response to what they feel is a bias against white students on their campuses.

- The election of the nation's first nonwhite president has contributed to an alarming increase in hate groups and antigovernment groups in the United States (Ohlheiser 2012),

- Even with a black man sitting behind the desk in the Oval Office, a disproportionate number of black men—over one million—are incarcerated in the United States (Ogletree 2012).

- Most Native American mascots, such as the University of North Dakota's Fighting Sioux, remain significant sources of conflict between Native Americans and non-Natives (Borzi 2012). (This text uses the terms "Native American" and "Indian" interchangeably.)

The Significance of Race

Despite the undeniable racial progress that has been made during the twentieth century, ongoing racism harkens back to earlier eras through racial imagery, for instance. As the opening vignette describes, nooses, visible reminders of an era when whites lynched African Americans, as well as Mexican Americans, Native Americans, Jewish Americans, and many other racial minorities, for real or imagined offenses, are still hung today to intimidate people of color. Lynching imagery was pervasive on the Internet during President Obama's candidacy and eventual presidency (Feagin 2012). In 2007, a noose was hung on the office door of an African American professor who taught courses on race and diversity at Columbia University. That same year on the same campus, a Jewish professor found a swastika on her office door. Both are professors of psychology and education and involved in teaching multicultural education.

What is the message being sent by this kind of racial imagery? The black high school student in Jena, Louisiana, President Obama, and the professors targeted in these examples violate what Feagin et al. (1996) refer to as racialized space, space generally regarded as reserved for one race and not another. Both that particular area of the high school campus in Jena and Columbia University were being defined by some students as "white space," a racialized space where nonwhites are perceived as intruders and unwelcome. Additionally, research on the experiences of Latino college students finds they often refer to institutions of higher education as a "white space," thus, an environment where they feel less than welcome (Barajas and Ronnkvist 2007).

Are these isolated incidents? According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a nonprofit group that tracks hate crimes and hate group activity, the prevalence of nooses and other symbols of hate, such as swastikas, are not unusual. Often such incidents are explained as a practical joke, which begs the question, what exactly is funny about a noose? A noose is the ultimate symbol of terror directed primarily, but not exclusively, toward African Americans. This symbol is hard to joke about. The parents of some of the white students in Jena explained away their high school children's behavior as a combination of ignorance and humor. We have to challenge such assumptions in the face of the history of this gruesome ritual.

Lynching is generally regarded as a southern type of mob justice perpetrated by whites against blacks. Indeed, the great majority of lynching's fit this profile and thus became the focus of a major antilynching movement during the first half of the twentieth century (which will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 4). However, many more racial/ethnic minorities were targeted for this type of violence. Part of the perceived "taming of the West" involved the lynching of hundreds of Chinese, Native Americans, and Latinos, particularly Mexicans, by Anglo-Americans (Gonzales-Day 2006), In Atlanta, Leo Franck, a Jewish factory manager from Brooklyn, was lynched for the murder of a young female factory worker, despite the fact that the evidence overwhelmingly pointed at someone else as the perpetrator of this crime. After the conviction of this man, a mob broke into the jail and dragged him off to be lynched, rather than allowing his conviction and life sentence to stand. The defendant was described as someone worthy of paying for this horrendous crime, "not just some black factory sweeper, but a rich Jew from Brooklyn" (Guggenheim 1995).

Lynching was a public act—often occurring at night, nevertheless, drawing large crowds of supporters. Photographers routinely captured such moments and often these photographs were made into postcards for popular consumption (Gonzales-Day 2006). Sociologically speaking, the use of public execution is meant to send a message to all members of the community. These are acts of terror, not just actions meant to punish one particular individual; terror is designed to instill fear in more people than the individual or individuals targeted. Thus, anyone currently teaching courses that challenge white supremacy could well interpret the hanging of a noose or a swastika on a professor's door as being directed at them as well. The presence of souvenirs and postcards complicates the picture; beyond terrorizing minority communities, it becomes a morbid celebration of dominant group privilege.

Not long after the hanging of nooses at the school in Jena and at Columbia University, an African American man has been elected president for the first time in US history. The success of Barack Obama's presidential campaign clearly indicates progressive social change. So, what can we make of an era when nooses are still being hung yet a black man finds tremendous support for his presidential candidacy? Such contradictions are actually part of a long history of societal contradictions surrounding the issue of race and are quite common; these may even become obvious to us if we take the time to reflect on some of the lessons we have been taught about race. According to white author and professor Helen Fox, "Everything I learned about race while growing up has been profoundly contradictory. Strong, unspoken messages about how to be racist shamefully contradict the ways I have been taught to be a good person" (2001:15). Students often note that they have been taught to love everyone because "we are all children of God," while simultaneously warned against interracial dating. Clearly, there is a fundamental, though often unrecognized, contradiction embedded in such messages.

Reflect and Connect

Can you identify any contradictory messages surrounding race that you have been exposed to through the media, at home, in school, or in church?

Defining Concepts in the Sociology of Race and Ethnicity

This book approaches the study of race/ethnicity through a sociological lens. Sociology refers to the academic discipline that studies group life: society, social interactions, and human social behavior. Sociologists that study race and ethnicity focus on such things as historical and current conflict between racial/ethnic groups, the emergence of racial/ethnic identities, racial/ethnic inequality and privilege, and cultural beliefs about race/ethnicity, otherwise referred to as racial ideologies.

We live in a culture where the meaning of race appears to be clear, yet scientists challenge what we think we know about race. Race specifically refers to a group of people that share some socially defined physical characteristics, for instance, skin color, hair texture, or facial features. That definition more than likely reinforces our common understanding of race. Most of us believe we can walk into a room and identify the number of different racial groups present based upon physical appearances. But is that really true? Many people are racially ambiguous in appearance, for any number of reasons, including the fact that they may be multiracial.

A term that is distinct from race, yet often erroneously used interchangeably with it is ethnicity. Ethnicity refers to a group of people that share a culture, nationality, ancestry, and/or language; physical appearance is not associated with ethnicity. Both of these terms are socially defined and carry significant meaning in our culture; they are not simply neutral and descriptive categories. A challenge social scientists offer is to understand race and ethnicity as social ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part 1: Thinking About Race

- Part 2: A Sociological History of US Race Relations

- Part 3: Institutional Inequalities

- Part 4: Contemporary Issues in Race/Ethnicity

- References

- Index