![]()

Chapter 1

Transport Issues and Their Solutions

1 Defining Transport

According to Hoyle and Knowles (1998: 1), transport exists to “provide for the movement of people [and] goods and for the provision and distribution of services … Transport thereby fulfils one of the most important functions and is one of the most pervasive activities in any society or economy”. Faulks (1977: 16) adds that the movement of passengers or goods should “occur from where they are to where they would prefer to be or to where their relative value is greater” – that is that the action should have a purpose. And Cole (2005: 5) notes “transport is a service rarely in demand for its own characteristics. Demand [for transport] is usually derived from some other function”.1 Two further key elements that make transport what it is, are the spatial and temporal dimensions involved.

Thus, transport can be said to involve movement of people and goods, be purposeful, and (generally) only occur as a consequence of other activities taking place in different locations at different times.

1.1 The Importance of Transport

In terms of the importance of transport, Vuchic (2007: 1) notes that “the founding, shaping and growth of human agglomerations throughout history have been products of complex interactions of many forces. One major force has always been transportation … ”. He continues that transport specifically has had a major role in determining the locations of cities, their size, urban form and urban structure. On similar lines, Headicar (2009: 1) begins his book with the phrase “transport is a vital part of everyday life” and Shaw et al (2008: 3) states that “the importance of travel and transport to the functioning of our economies and societies is hardly in doubt, but the very ordinariness of transport systems often means that they are taken for granted”.

Transport then, is a subject worthy of further study. And as good a place to start as any, is with the transport system – that is the means of effecting transport.

1.2 The Transport System

The physical and social worlds are full of change, paradox and contradiction. There is no simple unchanging stable state … Systems are patterned, regular and rule-bound, but through their workings they can generate unpredictable features and unintended effects (Dennis and Urry 2009: 48).

Such a comment is especially appropriate for transport, which although relatively easy to simplify – at a basic level the transport system can be said to comprise of fixed elements or ‘infrastructure’ and mobile elements or ‘vehicles’, that interact with each other in compliance of a series of rules – in actuality is extremely complex.

This complexity stems from the fact that the transport system does not exist in isolation (almost by definition as noted earlier). It is therefore appropriate to set out some of the factors that influence the transport system and in turn at how it impacts on other sectors.

2 Influences on the Transport System

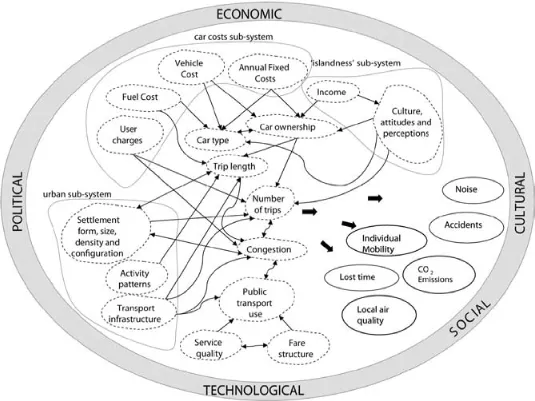

Before this step is made though, it is helpful to refer to a visual representation of a highly simplified series of interactions made from a transport planning perspective (see Figure 1.1), which provides some idea at least of how these elements interact with each other.

Specifically, a range of political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental factors combine to influence the demand for transport in an area. These ‘demand factors’ can be grouped into ‘sub-systems’. For example, the urban sub-system comprises activity patterns, transport infrastructure and land use related factors, while the car costs sub-system includes information relating to the cost of motoring. The next step occurs where the sub-systems then influence the organisation and operation of transport elements such as car ownership levels, number of trips, length of trips, level of public transport use and the interaction of these then generates the resultant transport-related impacts (for example, personal mobility, congestion, noise, air pollution).

2.1 The ‘Unique Demand Profile’

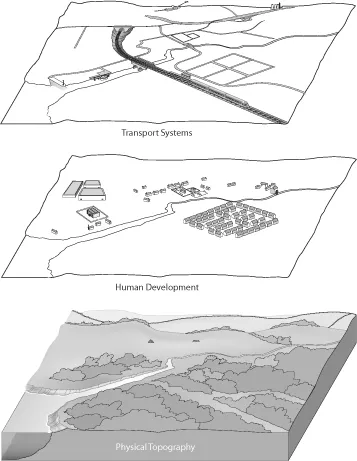

A slightly different way of trying to model the interactions within the transport and the wider system is to think of every square kilometre of land as being unique in terms of the amount and type of transport it needs.

On choosing one of these ‘Unique Demand Profiles’, each rather like a fingerprint, the next step is to break it into three separate components (see Figure 1.2). The first of these is the natural or physical terrain (or topography) of the location. This is the ‘baseboard’, or the land with no human contribution. The second component consists of the human development (houses, shops, factories, schools and so on) which form the ‘demand’ generating activity centres. The final component comprises roads, railways, airports and vehicles of the transport system – that is the ‘supply’. Put these three components together and then connect them to other similar UDPs in the form of a jigsaw puzzle, and one has a transport system.

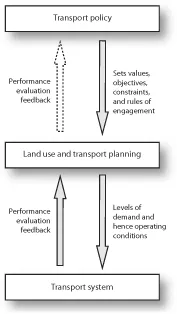

Developing this model further, it is possible to see how the roles of the transport operator, the transport planner and the transport policy maker might interconnect (see Figure 1.3). In brief, the transport policy maker sets out the values, objectives, constraints and rules of engagement to inform the task of the transport planner, who in turn directly influences the levels of demand (and hence the operating conditions) of the transport operator. Feedback on the performance of the system is then passed from the transport operator to the transport planner and from the transport planner to the transport policy maker to complete the loops.

Figure 1.1 Influences on the transport system

Source: Warren and Enoch (2010). Reprinted with permission

Figure 1.2 Unique demand profiles and transport

Figure 1.3 Stakeholder roles in transport

2.2 Travel Demand and Supply Characteristics

Understanding the Unique Demand Profile concept is a start, but in addition there are several important features relating to the nature of the demand and the supply of transport which help explain why the topic is so difficult to deal with. Thus, Ortuzar and Willumsen (1994) notes the special features of travel demand are:

• First, the demand for transport is qualitative (that is lots of attributes are not quantifiable).

• Second, it is differentiated (by time of day, day of week, journey purpose, importance of speed and frequency). This means that transport demand is very difficult to analyse and forecast and that any service without these attributes being matched may well be useless.

• Third, transport is a derived demand, not an end in itself. This means that we must understand how facilities to satisfy these human needs (work, leisure, health and so on) are distributed over time and space. A good transport system widens opportunities for people to undertake these activities, while a congested and/or poorly connected system restricts options and limits economic and social development.

• Fourth, transport demand is heavily governed by space – this means it is the distribution of activities over space which makes for transport demand and so in the vast majority of cases space must be explicitly considered. The most common way of approaching this is to divide study areas into zones and to code them together with transport networks. This spatiality of demand often leads to problems where, for example, there are too many people and not enough taxis in one area and too many taxis and not enough customers in another.

• Also important is the dynamic element of transport. So, a good deal of transport demand is concentrated on a few hours each day, in particular in urban areas where most of the congestion takes place during peak periods. This time variable nature once more adds a further layer of complexity.

Meanwhile, the same book reports that the supply characteristics are:

• Transport supply is a service and not a good. In other words, transport cannot be stored (so as to save it up for times of peak demand) but must be consumed when produced, otherwise benefit is lost. This is why it is so important to predict demand as accurately as possible so as to use resources as efficiently as possible.

• Many of the characteristics of a transport system derive from being a service. In broad terms, a transport system consists of a number of fixed assets (infrastructure) and a number of mobile units (vehicles). The movement of goods and people becomes possible when these are combined together with a set of rules for their operation.

• Further complexity is caused in that the supply of transport is shared among a whole range of government departments and agencies, developers, businesses, operators and travellers. This has economic implications too, in that travellers often do not pay the actual cost of using the transport system meaning it is not used as efficiently as it might be.

• Next, the provision of transport supply is lumpy – in other words one cannot provide half a runway, or a third of a bus. It is often therefore difficult to match the supply with the demand because of this. Related to this is that investments in transport infrastructure are not only lumpy, but can take many years to carry out. Furthermore, disruption during the construction phase involves additional costs to users and non-users alike.

2.3 Balancing Demand and Supply

Fundamentally, the task of the transport planner is straightforward. It is to match the demand for transport by society with the supply or so-called capacity of the transport system in a given place at a given time. Yet as has just been noted, while simple to articulate, this is complicated to do. Consequently it is maybe surprising just how often the ‘ideal’ situation where demand and supply are in balance (or something close to it) occurs. In many locations and for much of the time though, either the level of transport demand is too high for the amount of available capacity (supply), or else the demand is not sufficient to make efficient use of the supply.

The next section explores these two cases in a little more detail.

2.4 Where Transport Demand Outstrips Supply

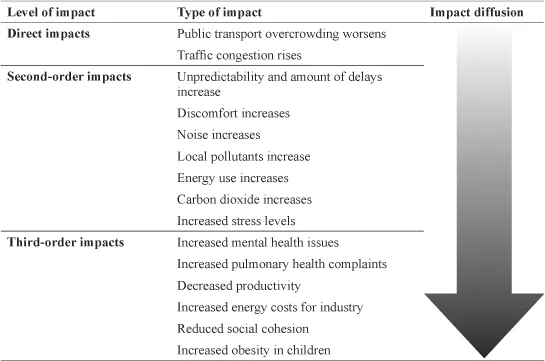

Where (and when) there is too much demand for the available supply it can be seen that a series of impacts result at a series of deepening levels (see Table 1.1 for an illustrative representation of the point made in this section).

At the initial direct level, public transport vehicles become overcrowded whilst road networks become congested. Such effects lead to second-order issues whereby discomfort and (often unpredictable) delays result. In addition, noise and local pollutants (carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxides, particulates) increase, as does the amount of energy and carbon dioxide used, and road traffic ‘accidents’ become more likely. Subsequent third-order effects at the individual level see delays and noise, for example leading to stress with implications for mental health (and by extension family relationships); whilst local pollutants contribute to pulmonary-related health conditions such as asthma. Meanwhile at the community level, aggregated delays in the transport system (made worse by the uncertainty) alongside the worsening health effects reduces productivity and increased energy use further increases costs, thus negatively affecting the economy. And social cohesion is damaged as children no longer play on the streets and people see less of their neighbours due to rising levels of traffic.

Table 1.1 Impacts where transport demand exceeds supply

2.5 Where Transport Supply Exceeds Demand

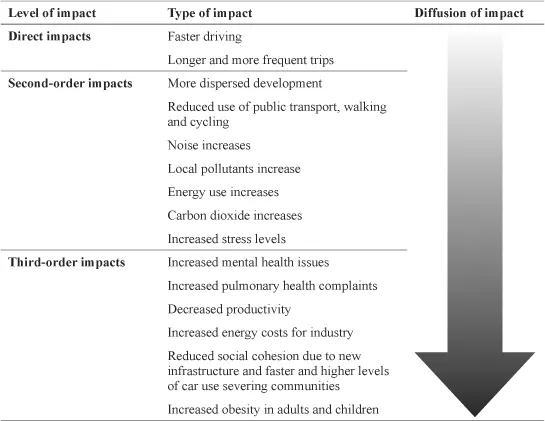

In the case where there is too little demand for the capacity provided, the causality chain operates in a different manner to that described in the previous section although there are also some similarities. Here, where road space is increased the behavioural impulses are for people to drive faster, to make longer trips more often and at times more convenient to them (typically in the peak), which in turn implies that development patterns become more dispersed leading to greater overall vehicle kilometres travelled and reductions in public transport and non-motorised trips. Following on from this, one might expect there to be more road traffic accidents, increased energy use and carbon dioxide emissions. One might also expect poorer health – both in terms of higher levels of obesity in adults and particularly children due to less physical activity, and in mental health from people being forced to travel further to live their daily lives. Meanwhile, the damage to social cohesion by reduced social interaction is this time caused by the health effects just referred to together with severance effects (where additional road or rail infrastructure coupled with higher traffic speeds). Table 1.2 provides a diagrammatic representation for this section.

Table 1.2 Impacts where transport supply exceeds demand

However, perhaps the main issue where and when supply outstrips demand concerns the wastage of resources (such as transport capacity, capital investment, operating subsidy, time, land, energy and especially political capital). This is a crucial point in a resource constrained world, and means that the environment whereby demand outstrips supply is becoming increasingly dominant.

2.6 Quantifying these Effects

In attempting to quantify these impacts, one of the most recent and comprehensive sources of evidence is the External costs of transport update study, which reports cost estimates for the year 2000 using statistics for 17 European Union States (EU-17) (Schreyer et al 2004). This separates the congestion effects from the remainder and reports figures for three congestion-related approaches, thus:

• If welfare theory is used to take account of costs arising from the inefficient use of existing infrastructure, a figure of €63 billion is derived (just over 0.5 per cent of GDP);

• If the optimal congestion charging amount was levied, revenues would be €753 billion (almost 8.5 per cent of GDP); and

• If loss of time was the indicator the cost would be €268 billion (3 per cent of GDP).

Meanwhile, the total external costs caused by transport activity on the rest of society excluding c...