This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Liberated Female

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book examines the Hungarian experiment to liberate women from servitude. It provides details on the problems of Hungarian women in employment, in the household, and in the sexual relations and outlines the social policies of the government and the patriarchal culture values in society.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Liberated Female by Ivan Volgyes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Long Road to Freedom

Chapter 1

The Idea of Liberation

What does liberation mean to a woman? According to the simplest and perhaps most accepted definition, it means liberation from age-old traditions of oppression. To a woman, it means being liberated from "negritude," to be able to work on her own away from the home and not be relegated to second class work-citizenry; being "merely" a housewife is denigrating, while having a "profession"—going away from the home to accomplish socially useful and meaningful tasks—equalizes the woman's role. Therefore, the idea of liberation has first of all to do with the concept of work and the relationship of women to work.

The second area of liberation relates to the role of women as "subjects" of men, as subordinates who are not given a chance for free development in male-dominated fields. Primarily men suppress women socially by not allowing them to express their opinions nor to develop their own abilities in order to keep them as sex objects. Therefore, if women are to be liberated completely from their oppressors, so the argument goes, sexual roles must be equalized. This second area of sexual liberation is related to professional liberation and the negritude of women in housework. Men are the breadwinners and expect to be treated at home as some seigniorial "lord of the manor" while women are relegated to the kitchen, to washing, cooking, and cleaning and are expected to be content with their lot. No one expects the "breadwinner" to take part in housework—he is free to come home, get his beer can, and enjoy his leisure. The "unpaid" work of women goes unnoticed and unrewarded, but it is expected. Ergo, if women are to be liberated, household responsibilities have to be equalized with men doing their share and women free to engage in other activities as partners of equal status to their mates.

Finally, the concept of liberation includes the woman's role in public life. Women's spare-time work in charity and volunteer organizations goes largely unrewarded, and their role in public life remains limited. If women are to be liberated, the area of public service must be opened to them, forcibly if necessary, and they must be given opportunity to represent at least their own interests in creating a more equal society of the future.

Thic concept of women's liberation has made great headway in the United States and is expected to serve as a policy guide for future development. Once implemented, it will be of great practical value in reaping the creative energy and assets of a portion of society heretofore only used to a limited extent. But the notion of women's liberation has been practically implemented to a much greater extent in other societies, and it would be well to examine their experience while ours is still at an early stage. It has primarily been the socialist societies of Eastern Europe that have officially proclaimed equality, prohibited discrimination against women as a matter of official policy, and accepted the right to work as the key that will open up the doors for women to realize their full potential. Our aim is to describe the experiences of socialist Hungary in the liberation of women although, where appropriate, comparative data will also be used. The importance of the topic in Hungary, the availability of material, and the relatively easy access to diverse officials prompted our selection of that country. Other favorable considerations were the approximately equal level of male and female employment, the relatively advanced industrial development of the country, and the side-by-side existence of urban and rural areas.

We do not mean to suggest that the path American women are following will be the same, nor even that the road travelled by Hungarian women should be emulated. The purpose of this book is to describe one road that has been travelled by women in another part of the world, to point out the potholes, the detours and—in the absence of a road-map—attempt to discern where that road might lead. By trying to skirt potholes, find short-cuts, and avoid detours and by trying to discover the end of the road from a "bird's-eye vantage point," we hope to stimulate discussion and to add to the list of "dos" and "don'ts" in our efforts to achieve an honest and just equality of the sexes and thereby harness the potential energy of the entire society in the creation of a better world for us and for generations to come.

Chapter 2

Oppression Anyone? A Brief Historical Perspective

The history of oppression of Hungarian women more or less parallels that of other women, but the interest of this particular nation lies within its "more or less." The road to modernity and ostensible liberation has been a long and arduous one, a road that mirrors in miniature the development of the nation as a whole. The progress made by Hungarian women has not been continuous. Quite the contrary, there have been both advances and setbacks typical of the ups and downs of the nation itself.

We know very little of the legal or factual status of women during the period of tribal migration before the Hungarians settled in the Carpathian Basin. The first accounts that deal with the role of Hungarian women come from Gardis, a Persian historian of the eleventh century, who described marriage customs among Hungarians around 900 A.D., customs that more or less prevailed until the ascendance of Christianity in the eleventh century and that continued thereafter with little change.1

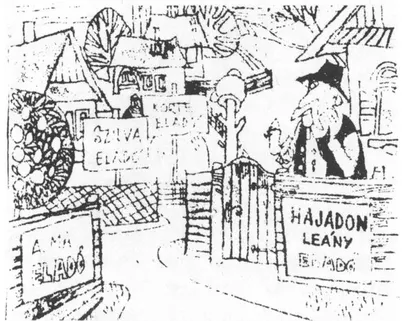

According to Gardis, the ancient Magyars apparently differed little from other primitive eastern tribes in their custom of buying women. A purchase seems to have been based upon a contract between buyer and seller, the buyer usually being the father of the groom and the seller the father of the young woman. The etymology of early words—some of which are still in use—reflect this early custom. Thus, nearly all words relating to marriage of this period refer to the woman as a product and to the marriage as a transaction. A young girl of marriageable age, until very recently, was referred to as elado lany (girl for sale), courting as leanyvasar (girl purchase), a young bride-to-be was called ara (a word derived from aru (goods for sale). The groom is still called volegeny a word derived from vevolegeny (a young man who buys); and a son-in-law is referred to by his father-in-law as vo (a word derived from vevo (buyer).

Among signs advertising the sale of apples, plums and pears, the sign on the right reads: For sale: a young maiden

Source: Ludas Magazin (Budapest), 4 (1971), p. 11.

Source: Ludas Magazin (Budapest), 4 (1971), p. 11.

Even present-day village customs have retained their ancient forms of buying and selling. In Kalotaszeg, Western Transylvania, the coin that a father gives to the son whom he considers ready for marriage is given in turn as a token to the girl or the girl's father. In the same village, another vestige from these rather barbaric times is the presentation of a cow to the bride-to-be's household.

It should be noted, however, that these "purchases" and purchase contracts were probably regarded as symbolic after the tenth century, and, in all probability, the bride brought an equivalent amount to the groom after the marriage. The notion of the woman as subservient to the man has continued right down to the second half of the twentieth century; indeed, even today many women refer to their husbands as uram (my lord) rather than ferjem (my husband).

Following the settlement of the Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin and the subsequent adoption of Christianity, the legal status of women was more clearly codified. The previous, apparently common custom of stealing or robbing a family of a girl child of marriageable age was outlawed by two of the early kings of Hungary in 1035 and in 1100, respectively.2

It is also possible that during these early years polygamy was still practiced to some extent in Hungary, but no concrete historical proof attests to this fact. There is no doubt, however, about the complete patriarchal control of the entire family, including the wife. This control extended to decisions of whether and when a child should marry and whom she should marry. The power of the father in marriage matters remained nearly absolute until the twentieth century. Furthermore, this patriarchal control underscored the legal status of a woman as a servant to all males within the family. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, women frequently were referred to—especially in villages—as fehercseled (white servants) or vaszoncseled (cotton servants) or, more benevolently, following Biblical traditions as asszonyi allat (womanly animal). It is not an exaggeration to state that until very recently women have been regarded as the slave in a slave-slaveholder relationship, a relationship that is expressed in a husband's possession of "rights" over his woman and the delegation of certain duties to women. The wife was expected to address her husband formally as on, maga (vous) or Kegyelmed (your lordship), while the husband could refer to his wife as te (tu) and be familiar with her. These medieval customs were, unfortunately, only abolished with the adoption of laws and ordinances in the first part of the twentieth century that altered the relationship of women from that of a subect to feleseg (wife); the literal semantic meaning of the Hungarian term for wife implies a half of the whole of marriage. Even though this uniquely egalitarian term originated in the fifteenth century and was already in widespread use in the nineteenth century, the content of the term has not been accepted by most Hungarian males until very recently, and some Hungarian men still reject the connotation of equality.

Until the Turkish occupation, Hungarian women, by and large, were under the tutelage (Geschlechtsvormundschaft or tutelle du sexe) and guardianship of their male relatives (fathers and brothers). The 1514 statutes that codified existing laws and customs clearly state that prior to marriage women are to be under the tutelage of their parents and male relatives.3 Contrary to the practice of other European states at that time, however, most Hungarian women, in fact and in theory as well, managed to get out from under legal guardianship upon marriage, and the husband's rights were limited vis-à-vis his wife. These Hungarian laws were advanced and quite modern in their conception compared to other nations'; under them, married, divorced, or widowed women were regarded as independent and not under tutelage.

The concept of equality was similarly strengthened by the custom of the homagium (Gewere), or "blood price," by which a murderer could buy his freedom. Hungarian women seem to have been considered equal to men, inasmuch as the price for their homagium was the same as that for men, contrary to the practice in other states.4

It is also curious that medieval Hungarian laws recognized the right of the feudal lord to physically punish his servant but did not extend to the husband the right to physically punish his wife. Even though physical abuse at the hand of their mates has long been a part of the every day existence of Hungarian women, the men had no explicit legal right to do so.

During the Middle Ages and until the Turkish occupation, Hungarian women also enjoyed certain political rights. These rights were, of course, restricted and applied only to the aristocracy and to widows within that class. In the case of county or national elections, franchise rights were vested in the middle nobility, but widows had the right to vote in place of their deceased husbands. In the case of legislative rights, the widows of the upper aristocracy (from baron upward), were entitled to send representatives to Parliament. And finally, as far as holding administrative positions, both in their capacity as guardians of minor sons and as representatives of their deceased husbands, women in pre-1848 Hungary were entitled to fill such positions as Lord-Lieutenant of a county.

All of these political rights, however, were exclusive rights of the nobility and all of them were slowly nibbled away, first by the Turkish occupation, then under the subsequent Habsburg rule. Not until the latter part of the nineteenth century can we again begin to talk of women's rights. It should be mentioned that the remarkable experiment in national independence, the 1848-1849 Revolution against Austria, which has inspired the Western world as an example of courage and aspiration for freedom, was wanting in "liberal" ideas vis-a-vis the role of women. While extending the right to vote to the rest of the adult population of Hungary, the 1848 law specifically excluded women from the franchise and thus from participating in the political life of the country.

Nor was this inequality alleviated with the new laws in the early 1870s that otherwise began the liberalization of Hungarian political life. The 1874 election law again excluded women from the franchise. Voting rights were based on two conditions: a financial tax base and academic qualification.5 The first allowed the husband to include his wife's wealth in the required minimum sum to qualify for voting but did not allow women of wealth to vote. Furthermore, even if a woman acquired academic qualifications outside of Hungary (in Hungary women were not allowed to enroll in universities until 1896), they still remained voteless. The most noted case of this blatant inequality occurred in the case of Dr. Vilma Hugonnai, the first Hungarian woman doctor, who received her Doctor of Medicine degree in 1879 in Zurich, where she practiced until 1890 before returning to Hungary. It took twenty-two years for the all-male medical authorities in Hungary to recognize the "qualifications" of this great medical authority, at which time Dr. Hugonnai was 65 years old and only had ten years of life left to engage in medical practice and politics.

Hungarian reform movements to equalize the rights of the sexes date back to the time of the French Revolution, but the first successful reform legislation had to wait until the Compromise of 1867 which elevated Hungary to co-equal status with Austria in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After 1867, several legislative acts authorized women to sign IOUs, allowed them to change religions of their own free will and even to acquire trade licenses. It was largely due to the persistent agitation of such feminists as Countess Blanka Teleki, Klara Leovey, and Hermin Beniczky that these first major laws concerning women's rights were promulgated. In 1868, the Union for the Instruction of Women was established and the first school for women was opened. In 1875, the state was finally compelled to act and elementary and secondary schools for women were established.

As industrialization proceeded in Hungary, the joint pressures of the need for labor and more opportunity to participate in labor activity combined to open up more and more professions to women. In 1875, the National Hungarian Industrial Union adopted a program for the inclusion of women in manufacturing occupations. In the same year, the post and telegraph offices opened their doors to women. The hiring of the first woman shorthand secretary in 1870 required parliamentary approval, but her employment was followed by the use of women shorthand secretaries everywhere. And finally in 1871, for the first time in Hungarian history, a ruling was handed down declaring that the new male and female ratio of teachers' colleges must be the same, three each.6

A great boost to the feminist movement was given by the publication of the first Hungarian women's magazine the Nok Lapja (Journal for women) in 1871. It became an organ for feminist controversy, and, although it failed to be the direct forerunner of the movement, it certainly served as forum for pro-feminist opinions. In the political arena, changes were rapidly occurring as well. On January 13, 1872, the Hungarian Parliament became the first European parliament to advocate equal rights, thus paving the way for women's rights legislation. Although no legislation was passed in 1872, the discussion in Parliament fostered a new atmosphere leading again to rapid progress. In 1874, 1877, and 1894, laws were passed that laid the foundations for an elaborate protection of women in family situations; women were allowed to marry and divorce without parental consent, to become legal guardians of children, to rear children in a religion different from that of the father, and several other privileges.

At the same time, other events encouraged further reforms, notably the creation of several liberal, leftist-oriented unions that worked in close cooperation with the Social Democratic Party. In 1895, law and medical schools of universities were opened to women. In 1896, the first girls' secondary school was opened in Hungary. In 1897, a trade union for female office workers was organized under the presidency of Social Democratic activist Roza Bedy-Schwimmer. In 1901, the first women's college dormitory was established and two years later state jobs requiring academic degrees were opened to women. The Feminist Union was organized in 1904 and, finally, the Union of Hungarian Women's Organizations, a branch of the International Women's Council, was organized. The cause of female liberation was also advanced by three publications: Feminista Ertesito (Feminist bulletin) in 1906, replaced in 1907 by A No es a Tarsadalom (Women and society) and Egyesult Erovel (With united strength), first published in 1909.

Although the 1913 International Women's Suffrage Congress in Budapest gave a great impetus to the cause of Hungarian equal rights legislation, it was not until the end of the war and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Introduction

- Part I. The Long Road to Freedom

- Part II. Work That Liberates

- Part III. The Second Shift

- Part IV. On Motherhood

- Part V. The Third Shift

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography